One of the most complex issues facing sports, including hockey, is chronic traumatic encephalopathy, CTE, a brain disease associated with violent head trauma.

It has been six years since John Branch’s seminal reporting on the death of hockey fighter Derek Boogard, at age 28, and the advanced CTE which was found in a posthumous study of his brain.

CTE is an ever-growing issue in sports. On the legal and research fronts, the NFL is ahead of other sports. In June, the league announced its first payout in the legal settlement with the players for a player diagnosed with CTE. The amount was $4 million. Since CTE is still only confirmed posthumously, the player is dead. Neither the player or the recipient(s) of the money were identified.

The legal precedent set with the NFL only adds pressure to the NHL, where CTE issues are being fought over in court. Certainly the NHL can learn much from the work surrounding the NFL and its players. In addition to hockey and football, several other sports have identified CTE as a potential issue.

Professional sports exist in a complex world, with numerous stakeholders and interdependencies. To understand the issues and complexities with CTE, it helps to understand people who lived in these roles.

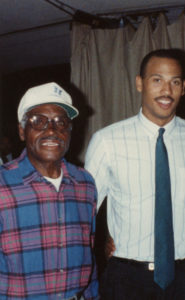

Howard Wright has lived many of these sports roles. I recently had the opportunity to interview Wright. He is an Intel Vice President, including responsibility for the Intel Sports Group. Wright’s life has intersected competitive sports, sports management, family, culture, science and, in a very personal way, CTE. We covered his story; from the genesis of CTE within his family to the challenges of addressing a disease with so many stakeholders, and finally discussing how technology will change our understanding of CTE and hopefully, contribute to its defeat.

Background

Wright is a former professional athlete; he brings a personal understanding of the culture of professional sports. In his role at Intel, he is involved with major sports leagues, including the NHL. In the process, he is exposed to the ways technology plays a role in addressing CTE along with the challenges to many communities who have a stake in addressing CTE. Wright played basketball at and graduated from Stanford University. He played in the NBA and other professional leagues in the US and overseas.

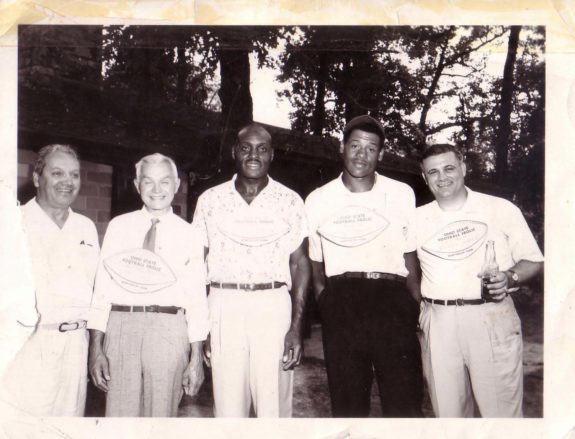

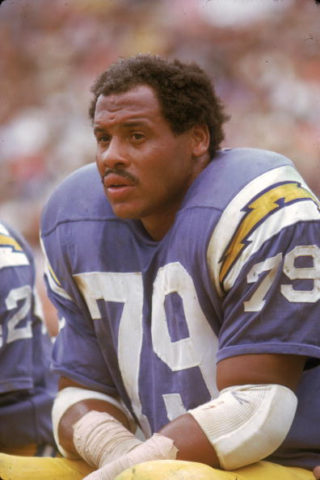

His father, Earnest H. Wright, played football for Ohio State, then was an offensive tackle in the AFL and NFL for 13 seasons, mostly with the Chargers in San Diego and Los Angeles. Following his AFL and NFL career, he was businessman, a sports agent and an executive with the players union. Ernie Wright, who passed away in 2007, lived his life with CTE.

The Interview

Zeke: You’ve said your father had CTE. Can you provide some background on this?

Wright: Starting as a teenager, he spent 20 years absorbing the most violent collisions, in a very small space with enormous men fueled by amphetamines. That’s like having how many car crashes in 20 years with paper-thin helmets? I remember stories of Pops telling me about him and other players of getting their bell rung, taking sniffing salts on the sidelines and then going back into the game. No concussion test, no doctor on the sideline to do even pedestrian procedures to prevent somebody from doing further harm to themselves.

The likelihood is he, and many other players suffered some form of CTE (note: a study by Boston University and the Department of Veterans Affairs found CTE in 110 of 111 former NFL players).

When Pops passed away (2007), it (CTE) was kind of becoming a thing. We knew players from that era were suffering and suffering greatly. I think it manifested itself in various ways, but he was somehow able to draw on his cognitive strength and have a brilliant business career.

My other siblings, we had varied relationships with our father. It was complex. When I was a kid, we lived in constant fear, he had a short temper and a wicked backhand. I stayed out of trouble because I lived in fear of bodily harm from my father. He didn’t physically abuse us children, we just got whupped. He never laid hands on my mother.

He excessively tried to self-medicate. He couldn’t sleep very well, he hardly ever slept. All those things contributed to a weird, atypical childhood upbringing. There was something which didn’t sit right. Ultimately he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. In those last 18 months, I got some peace with him. In all the hospitals and hospital beds, we had conversations we probably should have had years before. But he was finally vulnerable enough to share and explain some of the headaches and some of the terrible thoughts he had.

Zeke: Can you provide some background on your father becoming a football player?

Wright: When I’m on a long flight or having days where it is tough to get out of bed, I use my family history as fuel. I think about the indignities my grandfather went through, my lord, and what he put my father through to turn him into a man. Teaching him football in the backyard mud. To get us from abject poverty in Toledo, Ohio, to where we are now.

(Note: Wright has written a short piece on this family history)

My father was a self-professed “fat kid” at 13, when he decided to try out for football. His father had been one of the best high school players in the country in 1939, but because he was African-American, he was denied the right to play in the national championship game in segregated Florida.

My grandfather pushed him to become a great player in their backyard in Toledo. My grandmother described it, looking out the back window, “watching her husband beat the crap out of her oldest son.” They would line up in the mud, a three-point stance, and my father would come of the line and POW! get hit in the chin or the chest. Over time, it became steel on steel, which is how my father became a great football player.

Without my father putting his fingers in the mud, without my grandfather turning this self-described fat kid into a man and without that kid committing to become man, I don’t get to sit here. My father changed the destiny of all of us. I know he suffered then, he suffered when he was playing, and after he suffered after was done playing.

Zeke: How do you know he had CTE?

Wright: I’ve never seen anybody else switch so quickly from calm to violence. That rage. Spankings, grabbing, as if someone walks around normally, and immediately, in that same nanosecond, channels rage like that.

I kept hearing stories about this with former NFL players. We knew Junior Seau very well, living in San Diego (Seau committed suicide in 2012 at age 43), also Dave Duerson (committed suicide at age 50) and Tony Dorsett (showing CTE symptoms and his doctors believe he has CTE).

Then the movie (Concussion) came out about (former NFL player) Mike Webster, and when they put a name on the disease, I got a chill and said, “That’s what Pops had.” We made the rest of the family go see it.

Zeke: Your whole family saw the movie and said, “oh yes, we lived this.”

Wright: The entire Wright family will sign an affidavit to that effect. Yes, I’m speaking for all of us. You recognize this was abnormal and sometimes abhorrent behavior.

Zeke: You have a closeness to this issue very few people have. What are some of the things you see technology bringing towards helping this issue?

Wright: There’s the metadata. This is my hypothesis. Parts of the solution come from tangible, quantifiable science. And to get to the science, you need to get to the data. To get the data, you need to put sensors on and in helmets, shoulder pads, sleeves, socks and skates and everything else. Then you need to do the optical tracking which leads to the replays where you can (digitally) reconstruct the injury or incident.

If you have a deep catalog of all these player’s injuries, a doctor can say “show me similar incidents and tell me what happened medically, with the player.” The immediacy and proximity to the data is where Silicon Valley works with the ecosystem to solve this.

There is a responsibility from the players association and others to open the kimono a little bit more than they want to. I’m sure there will be trials. On the edge of everybody’s comfort zone, there is a solution here. I think there is a technical solution quicker than a contractual obligation and what the lawyers will let anybody find.

Could Silicon Valley help people on Park Avenue (league executives), the medical community and the players involved find a way to make CTE de minimus? There will be collisions, with the NHL and NFL, these are 100% injury rate sports. Are there things we can do with technology and the way the game is played, the way it is officiated?

When a player comes to the bench, there is a doctor who can do a full diagnostic, almost EKG scan on the player, based on the metadata. We’re anxious to help solve this. The doctor has to be trained in a very specific way.

We’re getting much closer to the solution because we have the sensors and technology with cognitive learning, artificial intelligence and predictive analytics that are all ready to be used in pursuit of a solution.

Zeke: Having played sports professionally, you know the athlete’s mentality towards injuries and toughness.

Wright: That will be the hardest to overcome. We have our own insecurities and hubris as a player. You are taught and trained “stay in the game, tough it out, shake it off, go back in.” Players live it and it is part of their identity. Its part of the sports psyche.

It’s almost impossible for a player to protect himself because of the idolatry and the way we deify the athlete. All of us want to be champions. The person least likely to ask out of the game is the person we have to protect the most. That is the player. The player is not exonerated from responsibility, but they are the least motivated to tap out.

The coaches, the trainers, the medical staff, it’s really right there. Seeing all the data after a collision, this responsibility falls at the feet of the medical staff on site. Medical doctors need to be arbiters, almost independent. They need to collect the data for stress or trauma to the head or neck. Get the immediate data points to put into the repository so we can examine what happens. Every rink, every stadium, every time so we get an understanding of what happens if the neck is twisted this way or a sensor gives a certain psi (pressure reading) indicating a level of stress or trauma to the head or neck. Each bit of data makes it safer for the next player who goes on the ice.

Zeke: Your father was both an agent and a union leader, two more stakeholder roles. What are the roles for agents and union leaders have in combating CTE?

Wright: The agents, the real agents that are worth a damn, want to see their players grow and make the transition, like my father did, from cleats to suits.

Player safety, player health, player longevity, player wellness, financial, physical, and emotional. This is why players associations exist.

I don’t want to place blame, everybody has a piece in this.

Zeke: Its seems to me it is the active players who have the loudest voices in the union, for example, they are the ones who vote for collective bargaining agreements. Do retired players need to have a louder voice?

Wright: Unions welcome other players from the past. A retired player generates information which can be used, lessons learned and best known methods. You get the voices of retired players, but the loudest voices are the prominent players you see on television all the time. My sense is the retired player needs a better voice in these unions to help the current generation of players.

Zeke: Any thoughts on how hockey differentiates from other sports?

Wright: I’ve met with Commissioner Bettman on other technology issues. Hockey is right up there as the best in-person fan experience. The playoffs are just a beautiful beautiful thing to watch. There is a really wonderful orchestration about hockey. You’re playing offense and defense. Players lay their bodies out for a chance to deflect a puck and stop a scoring chance. They 30 miles per hour go up and down the ice and are lighting each other up.

There is a beauty and savagery about hockey. It is violent in its DNA. Commissioner Bettman has called out most of the rogue, hockey goonish things from decades past.

Yet we saw it this year with Crosby among others, there will be concussions. How do we progress? Think back to earlier decades and all the improved safety gear.

In youth hockey, kids are much more protected now and much more protected in years to come. If the technical and business ecosystem in Silicon Valley can throw its acumen at the safety problems, that will be a wonderful use of our enormous skills.

Zeke: In regard to youth sports, will putting all these sensors into equipment price people out of hockey?

Wright: No, these technologies are in experimental labs now. We can easily fail fast and see what happened. We can correct and move towards commercial mass market. If we were to put sensors on every bit of a player’s connected uniform today, connected jerseys, socks, skates, it would be prohibitively expensive right now.

But there is no reason there won’t be perpetual growth and perpetual improvement until it becomes the new standard. This is going to be objectivity versus subjectivity. There will be millions of data points of experience at doctor’s fingertips. There will be more rapid improvement over the next three years than over the last 30. As Silicon Valley gets involved to help sports leagues, they will be unstoppable in their ability to improve themselves. Its Moore’s Law (a ‘law’ describing the exponential rate of developments in computer chips) applied to a different vertical.

As we take, curate and manipulate the data algorithmically, this gives Commissioner Bettman actionable intelligence to work with the teams and players association.

Zeke: Fistfighting is still very much a part of the hockey culture. The players expect it to continue. How do you see this in relation to CTE?

Wright: I don’t know. I go back to Olympic hockey and some of the wide open hockey from Eastern Europe and the Nordic countries. I don’t understand why Olympic hockey, so popular, and why it hasn’t translated to the NHL. I understand the visceral and primeval part where a dude has wronged you and so you stand toe to toe and figure it out. I think this is self-correcting, checks and balances are right there. For example, I haven’t see sucker punches for a long time.

Zeke: Do you see limitations inherent in the nature and spirit of the game which may counteract the advances we make with technology to reduce CTE?

Wright: There are things technology can’t solve. Like standing there with bare-knuckles and hitting another man as hard as you can.

But there is precedent for improvement. In the NBA 30 years ago, the game had much more dangerous play, like clotheslining and punching players. There were conscious steps taken to eradicate that from the game. (NBA) Commissioner Stern, under his watch, made this happen. Bettman was with the NBA at the time this happened and he was one of the co-architects of the changes.

If the NHL and Commissioner Bettman wanted to reduce or eliminate these dangerous plays, they could if they wanted to. It certainly isn’t like it was decades ago, when it was often a free-for-all.

Zeke: Over the course of our conversation, I’ve heard the conflicted nature of your relationship with your father. How football enabled so much, but how CTE took away so much of your relationship with your father. Could you to frame this for me?

Wright: If I ever had a son, I would never let him play football. I haven’t been to enough youth hockey to know if I’d let him play hockey.

I think of my father in wild extremes. God blessed me to have my father in my life for 39 years. I know I’m the luckiest guy ever. During those 39 years, I saw comfort, compassion, wisdom, eloquence, regalness. I also saw brutality, rage, insecurity and excessive self-medicating.

I wrestle with it myself. What part of him do I want to keep and what part do I want to extract as if it were a cancer cell. I am conflicted on this topic quite a bit. He is the most complicated person the good Lord ever put on this planet.

All that said, there are some things which just can not be explained, one human to another. I’d bet everything I have he was affected by CTE. Now we learn from the mistakes of the heroes who came before us.

Maybe he didn’t know what he was doing would cause such severe and debilitating damage to him over decades. He fought his demons which were exacerbated by traumatic, repetitive, blunt force blows to the head.

But, I’d bet he’d take all those hits, sacrifice all of that, get hit in head over and over again, to give his family a chance to go higher than he was able to go. Its conjecture, we never had that conversation. He did change the trajectory of every single Wright family member who came after him. In exchange for that, God gave him a tough sentence.

I use his history to amplify my destiny. I pay homage to him and pay it forward to my children and the children’s community charities we support. I am a grateful son.

Zeke’s Notes

In the context of trying sensor combinations on players, Wright used the term, “failing fast.” This term might confuse some readers. Failing fast is part of a business philosophy called “design thinking.” In this context, it means going through the design phase of a project quickly so one can begin testing at the earliest possible time.

The concept relies on short cycles composed of designing, building, testing and learning. The learning from each cycle allows a smarter design process for the next cycle. By shortening each of these cycles — or failing fast — there are more learning cycles. This results in a better product in less time.

* originally published in July 2017