Going into this weekend, the high-flying Chicago Black Hawks sit atop the National Hockey League standings. Tied with the Detroit Red Wings, Chicago has 54 points, although the Red Wings do have a game in hand.

If the Hawks can continue their pace and stay ahead of the pack, they will finish in first place for the first time. And if they do, “The Curse of the Muldoon” will finally be put to rest. Or will it?

The Muldoon Curse

Who was Pete Muldoon and what is this curse that is mentioned whenever the Black Hawks ascend to the zenith of the NHL standings? It is the stuff of hockey lore, and whether true or not, it makes for great hot stove conversation.

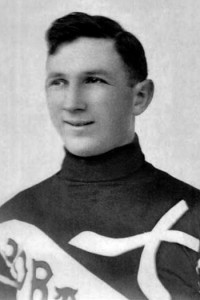

Pete Muldoon was the first coach of the Chicago Black Hawks. He was a native of St. Mary’s Ontario, born Colonel Linton Treacy in 1887. He played hockey in Ontario as a youth but moved to the west coast in the early 1900s to pursue a boxing career.

He changed his name to Pete Muldoon because pursuing a professional sports career was frowned upon in Ontario at the time. He also felt the name was more suitable for a boxer. He won regional titles in both the middleweight and light heavyweight divisions, but never did turn professional as a boxer. Hockey always was his first love, but he was adept at other sports. He was also an accomplished lacrosse player and played the sport professionally in Vancouver in 1911.

Playing-Coach at Portland

He got into coaching with the Portland Rosebuds of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association at the age of 27 when he was appointed player-coach in the 1914-15 season. He led the team to a second-place finish with a 9-9 record.

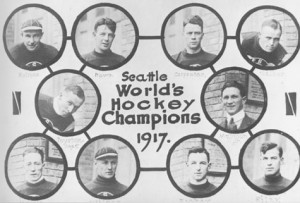

He moved to Seattle the next season to coach the Seattle Metropolitans of the PCHA. After a third-place finish in his first year at the helm, Muldoon led the Metropolitans to 16-8 record and first place in 1916-17. A playoff win earned the Metropolitans a shot at the Stanley Cup against the Montreal Canadiens.

The 1917 Stanley Cup playoffs saw the Canadiens defeated by Muldoon’s Seattle team. The Metropolitans thus became the first American team to win the Stanley Cup. Muldoon remains, to this day, the youngest coach of an American team to win a Cup, and the first to bring the Stanley Cup south of the border.

Wouldn’t Accept Forfeit

Muldoon had a chance at a second Stanley Cup in 1919. The Metropolitans again challenged Montreal. Tied at two games apiece, the fifth game ended in a 0-0 tie. A sixth game was scheduled to decide the championship but fate intervened.

Just hours before the scheduled start of the game, local health officials called it off when players from both teams were stricken by the Spanish flu. Canadiens were not going to be able to ice even a minimum squad and the PCHA vetoed a request to pick up local substitutions. Canadiens owner George Kennedy announced he was forfeiting the final game – and the Stanley Cup – to the Metropolitans.

Muldoon, however, was having none of this. He felt it was unsportsmanlike to claim the trophy from a team decimated by illness and refused to accept the Stanley Cup.

First Coach of Hawks

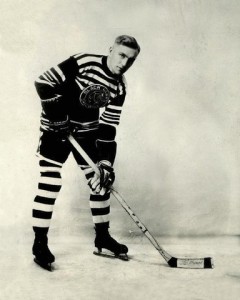

When Seattle folded after the 1924 playoffs, Muldoon returned to Portland. In 1926 most of the Rosebud players were sold to Major Frederick McLaughlin, who was the owner of the new Chicago Black Hawks of the National Hockey League. Muldoon was offered the position of coach of the new team.

With his wife a native of the Windy City and pregnant with their second child, the job as first Black Hawks coach was a perfect fit for Muldoon and he accepted the position. But working for McLaughlin was no bed of roses.

Muldoon loved his team and the players. And the players learned from Pete. Eight of the 16 Chicago players that season eventually went into coaching. One player who enjoyed great success as a coach was the legendary Dick Irvin. Irvin mentored both the Leafs and Canadiens to Stanley Cups.

McLaughlin, however was a thorn in Muldoon’s side. He constantly interfered with Muldoon’s coaching, making suggestions and even demands on how players should be used. Muldoon tired of the owner’s antics and with 14 days left in the season, he gave McLaughlin two weeks notice that he was resigning his position. Muldoon outlined his reasons for leaving quite eloquently:

“Our worthy president wanted to run the club, the players, the referees, etc. He learned the game very quickly. In fact, after seeing his first game, he wrote me a letter telling me what players should and should not do.”

The first-year franchise was moderately successful, finishing third in their division. Success eluded the team in the Stanley Cup tournament, and Muldoon, true to his word, left the team. He and his young family returned to Seattle.

Unfortunately, Muldoon succumbed to a heart attack in March of 1929 at age 41. Typically, he was on a hickey junket at the time of his death. He was travelling from Seattle to Tacoma to look for a site to build an arena.

The “Curse”

As for the famous curse, what really happened? As the story goes, when Muldoon left the Black Hawks, he was so disenchanted with McLaughlin’s meddling he told the Major that he was invoking an Irish curse upon the team. He vowed that the team would never finish in first place in the National Hockey League standings.

It’s always been a bit of a controversy as to whether that conversation actually took place. The participants in the exchange of words are no longer with us and witnesses, if anyone actually was present, are scarce.

The earliest reference to the Muldoon Curse is made by sportswriter Jim Coleman in 1943. He wrote that Muldoon was actually fired by McLaughlin. The reason for Muldoon’s firing boiled down to a heated confrontation between Muldoon and McLaughlin at the end of the season. As the story goes, McLaughlin felt that the Black Hawks were good enough to finish first in the American Division. Muldoon disagreed, and McLaughlin fired him. Muldoon supposedly responded,

Fire me, Major, and you’ll never finish first. I’ll put a curse on this team that will hoodoo it until the end of time.

Joe Farrell

Today, Coleman is not quite so succinct in his version of the origin of the curse. This week he said that the legend of the curse may be the product of the fertile mind of Chicago hockey publicist Joe Farrell. As Coleman puts it, Farrell seldom permitted strict truth to spoil a good story.

Coleman tells a yarn about a story that Farrell permitted to be circulated about a young, swift skater who came to the Black Hawks from western Canada.

Louis Trudel was a rookie who had exceptional skating ability and came from Edmonton to try out in Chicago. A Chicago reporter who was not terribly familiar with hockey or Canadian geography was awed by Trudel’s speed and grace on the ice. He sought out Farrell to get some information and background on the flashy rookie.

Farrell, possibly sensing an easy mark, gave the reporter a wonderful story on how Trudel built up his blinding skating speed. He told the scribe that Trudel had been a postman back on the prairies. Every day he skated down the Saskatchewan River, carrying the mail from Edmonton to Saskatoon and that daily trip built up the player’s legs.

The reporter, suitably impressed, printed Farrell’s background story in a Chicago daily paper. Coleman uses this example to illustrate how Farrell was entirely capable of concocting the story of the Muldoon Curse.

So, whether true or just another unproven legend, no one is quite saying. But the reality is, the Black Hawks have never finished in first place. This season, they have a shot at doing so. Can Hull, Mikita, Pilote and Hall prove to be stronger than a legendary Irish curse?

Or maybe, after 40 long years, it’s just finally time for the curse to be lifted.

(Authors Note: The Black Hawks finally finished first the very next year in the 1966-67 season. Jim Coleman finally admitted at that time that he made the entire Muldoon Curse story up when he was suffering writer’s block on a slow news day.)