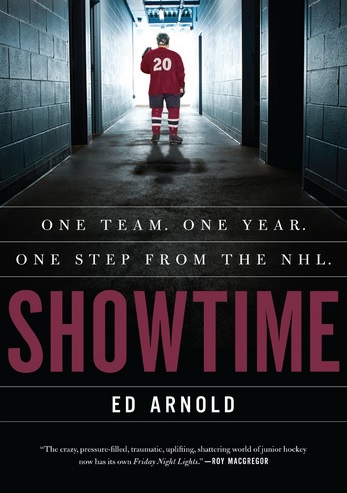

Showtime: One Team. One Year. One Step from the NHL by Ed Arnold (HarperCollins Publishers, Toronto. 2016)

Of the three Major Junior hockey leagues that fall under the umbrella of the Canadian Hockey League (CHL)—namely, the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League (QMJHL), the Western Hockey League (WHL), and the Ontario Hockey League (OHL)—the last one, the oldest one, has produced the most NHL players.

Among the teams in the OHL, the one that has sent the most players to the NHL is also the oldest team, the storied Peterborough Petes.

“Showtime” is journalist Ed Arnold’s recounting of the 2012-13 season for the Peterborough Petes. He was given full access to players and management for the course of the season.

Ideally, I suppose, when a writer is embedded in a team or a situation like this, the presumed ideal outcome is that the team makes a Cinderella run to the championship, and the writer is along for the ride.

Ideally, I suppose, when a writer is embedded in a team or a situation like this, the presumed ideal outcome is that the team makes a Cinderella run to the championship, and the writer is along for the ride.

This is asking quite a lot.

If you don’t follow the OHL or Major Junior amateur hockey, you don’t know the fate of the storied Petes for that season. And to be honest, it’s not all that important when reading “Showtime.”

Every year, the overwhelming majority of teams who compete for a championship have their season end in defeat. If everybody won championships every year, they would be worthless.

And to some extent, when Arnold began following the team, he had to be aware that, no matter what, this Petes team was not likely headed to the Memorial Cup. The team had missed the playoffs the prior two seasons. So although the Petes are a storied franchise, with Hall of Fame names attached to their past such as Steve Yzerman, Bob Gainey, Larry Murphy, Scotty Bowman, and Roger Nielson, as well as other familiar names like Chris Pronger, Mike Keenan, Derian Hatcher and many more, Arnold’s decision to hitch his wagon to this star could not have been motivated by the hopes of a championship, not even with players like future first round pick Nick Ritchie and second-rounder Eric Cornel, among others.

And in fact I would argue that that isn’t why any of us who follow amateur or minor pro leagues follow them.

Sure, a fan could have decided, two years ago, that they would follow the Halifax Moosehead of the QMJHL, with the hopes that they would be assured to see of their top players in the NHL one day, and they would not have been disappointed.

But that’s the exception. You don’t follow amateur or minor pro teams with the hopes that you’re seeing one or two superstars before they were stars. You may indeed see that player, but you learn quickly that for the other 99.9 percent of the time, that isn’t who you’re seeing.

Major Junior is as much a developmental league as the American Hockey League, if not much moreso. And it’s on this developmental aspect that Arnold trains his focus.

Hockey fans who regard the CHL as an inscrutable assembly of teams with somewhat familiar names based in cities they’ve never heard of and know nothing about would learn a lot about the development of their favorite NHL players from Arnold’s book.

For these players, Major Junior is the last time they will play hockey for free (relatively speaking). It is the final stop in their lives for the game of hockey to remain a game (relatively speaking), before it becomes a business (technically it’s already too late by then but the point remains).

Consider what Arnold writes about the kids entering the Petes’ training camp:

“They had all played all-star hockey while growing up. They had all been the top players on their teams. Many now playing defense had grown up as forwards; some of the forwards had played defense … Their parents had spent, on average, more than $100,000 … so that their sons could play at a higher level and chase their dreams.”

One hundred thousand dollars on average. And maybe three or four percent of them will reach the NHL.

Arnold also documents the schedules these players have to keep: long bus rides, high school classes, homework, temptations, trades, and so on. It would be hard to find an equivalent to what these kids endure while in high school in order to play Major Junior hockey. I’m not pitying them—nor does Arnold—but the schedule is brutal. And the OHL, like other CHL leagues, is serious about these kids not only playing hockey at their top abilities every other night, but also about getting good grades in classes they can’t attend a fraction of the time because they’re on a bus ride to Oshawa or to London.

Arnold’s description of the Petes’ rollercoaster season, replete with trades, firings, angry fans, a visit from Hockey Night in Canada, an extraordinary second half to their season, offers a glimpse into the complicated and politically charged machine that produces so many NHL players. You’ll never look at the OHL or the Canadian Hockey League in general the same ever again.

My only critique is that at times Arnold writes as though he feels compelled to inject some urgency or drama from this season where no matching drama exists. In other words, instead of feeling like that was an extraordinary season in the history of the Petes, my impression was that while perhaps it was in some ways, in most ways it was just another circus-like season in a small Canadian town that is home to Major Junior hockey.

And that alone, without any bells or whistles, makes Arnold’s book worth reading.

Showtime hits the book shelves September 16.