If you were asked who are the greatest hockey players of all time, it wouldn’t take very long before you said Bobby Orr. Through eight seasons from 1967-68 to 1974-75, Orr won the James Norris Trophy eight times, the Hart Trophy three times, the Art Ross Trophy twice, two Stanley Cups, and the Conn Smythe Trophy twice.

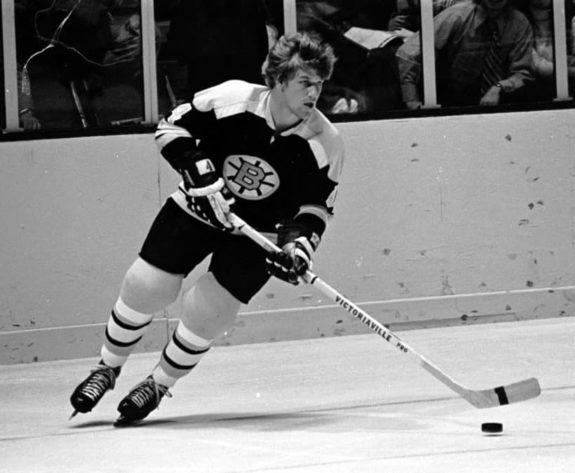

Those seasons, plus his rookie campaign in 1966-67, were the only nine seasons of his career when he played at least 61 games, which shows how brief yet impactful his NHL career was. The image of him wearing the Boston Bruins’ black and gold, dazzling fans at the Boston Garden with never-before-seen speed and skill, making passes and scoring end-to-end goals that made the thousands in attendance collectively say, “Wow,” is cemented in the collective psyche of hockey fans.

But when you look back on his career, his last three seasons are seldom remembered. You would be hard-pressed to find many highlights of him flashing that speed and filling the net with pucks.

Where Did Bobby Orr Finish His Career?

That’s because, between 1976-77 and 1978-79, Orr was a member of the Chicago Blackhawks. It feels profane to type it into my keyboard. “Blackhawks’ defenseman, number four, Bobby Orr.” Ugh, maybe I’m wrong and I’ve misled you. It must have been a typo on his Wikipedia page, there’s no way Orr wore the sweater of another team. Surely, there would be some photographic proof.

Sweet, fancy Moses! It looks…how can I describe it: strange? Awkward? It leaves you feeling uneasy. It’s like looking at Willie Mays wearing a New York Mets uniform, Joe Montana with the Kansas City Chiefs, or Michael Jordan with the Washington Wizards. Something’s just not right. When a player accomplishes so much with a team, we remember them exclusively wearing that jersey. I doubt your mind goes to Wayne Gretzky in a St. Louis Blues sweater or Mark Messier in a Vancouver Canucks jersey.

Related: Bobby Orr’s Landmark Season

But things happen. Players get traded, contract negotiations fall apart, and teams move on. So, how did Orr end up in Chicago? What led to the game’s greatest defenseman signing with another Original Six team and spending the twilight of their career in the Windy City?

Bobby Orr’s Tumultuous Final Season in Boston

Heading into the 1975-76 season, after which Orr would become a free agent, there were already signs that negotiations between player and team would be difficult. His agent Alan Eagleson, who was the first agent in hockey to negotiate a contract on behalf of their client, was playing hardball with the Bruins, demanding they guarantee any contract they offered Orr.

Many expected a deal to be done before the start of the season. However, the chronic pain in Orr’s left knee, which had already gone through three surgeries, forced him to undergo a fourth on Sept. 20. This shifted the mood in negotiations. Lloyd’s of London, the British-based insurance agency for the Bruins, refused to insure any future contract between Boston and Orr in case of injury.

Eagleson recommended Orr not play again until a deal was in place, but wanting to prove he could help the team and still compete, he made his 1975-76 debut on Nov. 8 against the Canucks. Held scoreless in his return, he scored five goals and 13 assists over the next nine games, looking like the version of himself that fans knew.

Those 10 games would be all he played in 1975-76, and as it turned out, the last he would ever play for Boston. He re-injured his knee for a fifth surgery, and his season was over.

Bobby Orr: First-Time Free Agent

According to Stephen Brunt’s 2006 book Searching for Bobby Orr, before the prior season even began, the Bruins offered Orr a five-year deal worth nearly $2 million with an interesting caveat: an 18.5% stake in team ownership. Eagleson said he ran the deal by NHL President Clarence Campbell, who said the league wouldn’t permit it since it violated league bylaws. However, Orr would later find out Eagleson never told him about the ownership provision, sabotaging the negotiations in order to earn himself a better chunk of commission.

Boston’s final offer after the 1975-76 season was a five-year deal worth $1.75 million, only guaranteeing $600,000. It was soundly rejected. Eagleson took great offense to the Bruins’ final offer (from ‘Bye-bye Boston, Chicago Buys,’ Sports Illustrated, June 21, 1976).

“They insulted Bobby with the type of contract they offered him,” Eagleson said. “I think the Bruins have indicated their conviction that Bobby is very badly damaged goods and not worth an unconditional contract.”

On June 1, 1976, Orr officially became a free agent. Eagleson sent a note to every NHL and World Hockey Association (WHA) team, excluding only the Bruins, saying if you were interested in signing the finest player of his generation, still only 28 years old, then contact him at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal on June 7.

“They insulted Bobby (Orr) with the type of contract they offered him. I think the Bruins have indicated their conviction that Bobby is very badly damaged goods and not worth an unconditional contract.” -Alan Eagleson

BYE-BYE BOSTON, CHICAGO BUYS, Sports Illustrated, June 21, 1976

The Detroit Red Wings made an offer, as did the Kansas City Scouts. Former Los Angeles Kings owner Jack Kent Cooke called Eagleson, as well as Blues’ general manager-coach Emile Francis. But all signs pointed to the Blackhawks being the leading contenders. Chicago President Bill Wirtz went on record saying he would sign Orr to the requested $3 million Eagleson was seeking.

After Orr flew to Montreal to meet with Eagleson and Wirtz, the Blackhawks made it official, signing Orr to a five-year, $3 million contract, guaranteeing every dollar (from ‘Orr Joins Hawks, but His Knee Is Doubtful,’ New York Times, June 10, 1976).

“We have gambled,” said Wirtz. “We have placed our bet down, but at least we have gambled on a thoroughbred.”

1976 Canada Cup was Bobby Orr’s Last Flash of Brilliance

After signing with the Blackhawks, Orr was invited to play for Team Canada in the 1976 Canada Cup tournament, the first best-on-best hockey tournament with professionals. Orr hadn’t played in the 1972 Summit Series between Canada and the Soviet Union due to knee surgery, so the opportunity to represent his country was something he didn’t want to pass up.

Even though his first goal of the tournament was spectacular, you can see Orr isn’t the same player we saw during his prime years in Boston. His knee is barely holding up, and the speed isn’t quite there. What you’re seeing is pure talent, running on fumes, and stickhandling skills. He led the tournament in scoring with two goals, seven assists, and nine points, helping Canada win gold. He was named the tournament’s most valuable player. It was the last glimpse of greatness we would see from Orr.

When The Hockey News released their 2000 book Century of Hockey: A Season-by-Season Celebration, they asked Hall-of-Fame forward Bobby Clarke how Orr looked through the tournament.

“Orr would hardly be able to walk on the morning of the game, and he would hardly be able to walk in the afternoon, and then, at night, he would be the best player on one of the greatest teams ever assembled,” said Clarke.

Bobby Orr’s Cup of Coffee in Chicago

After all the contract negotiations, surgeries, and public feuding, Orr was finally ready to play with the Blackhawks. Unfortunately, it wasn’t cinematic. During his first season, in 1976-77, he only played 20 games, struggling to even walk. He sat out the entire 1977-78 season. He attempted to make a comeback in 1978, playing in only six games before deciding to retire officially.

Looking back at Orr’s time in the NHL, it’s easy to say his brief stint in Chicago was a footnote with just 26 games over a three-year period, scoring only six goals and 27 points in a career that produced 270 goals and 915 points. Orr wearing a Blackhawks’ sweater is more of a trivia question than a memorable window of time.

But it did mean something. It represented a moment when a player entering free agency fought for what he felt he was worth. It highlighted what can happen when a player puts too much trust in their agent. It put a spotlight on what happens when a team pays for a player’s reputation instead of their future production. Finally, it showcased what happens when the relationship between a franchise and its greatest player deteriorates.

We remember Orr’s career for what it was. There’s still so much we forget that could have been.