There is an old adage that admonishes cutting corners and taking shortcuts while working on a project. It states that she/he who commits such an offense will later be forced to retreat and fix the error that was caused by their previous pursuit of the shortcut. For example, when hanging a shelf, double-check the location of your stud before you drive the nail into the wall. Otherwise, it might soon come crashing down.

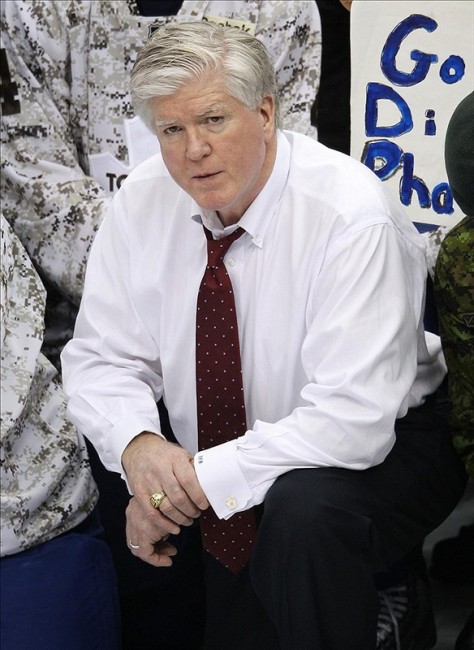

“I don’t think you can do a classic pre-salary cap rebuild here where you finish dead last three or four years and pick first or second,” said Brian Burke in October of 2009, less than a year after becoming the general manager of the Toronto Maple Leafs. The irony is, of course, that the Leafs finished nearly dead last the ensuing season, allowing the Boston Bruins to draft Tyler Seguin second overall with the pick that used to belong to Toronto.

The Burke philosophy on constructing a winner in Toronto has been to do it as quick as possible. This has meant that the draft has largely been shunned as a tool for building the team. The Kessel trade is an exemplary model of this philosophy at work.

Building through the draft takes time. Indeed, to commit to such a strategy is to take the long view. Burke’s philosophy is directly opposed to the long view. His philosophy, unsuccessful thus far in his tenure with Toronto, is best described as a pursuit of shortcuts: signing free agents and orchestrating blockbuster trades.

That’s not to suggest that a team being constructed via trades and free agent signings cannot compete for the Stanley Cup. It’s just that, since the lockout, the foundation of the majority of Cup finalists has been assembled through the draft. Consider the 2010 final between the Chicago Blackhawks and Philadelphia Flyers. At the time Jeff Carter and Mike Richards, both first round picks in 2003, were the bedrock of the Flyers franchise. The champion Blackhawks had several of their own emerging stars whom they recently drafted, including Patrick Kane, drafted first overall in 2007, and Jonathan Toews, drafted third overall in 2006. Suffering through losing seasons and retaining first round draft picks has been crucial to the success of several post-lockout teams. The Edmonton Oilers, for example, are currently a sleeping giant about to emerge from slumber. Nearly everyone in hockey expects the Oilers to run over opposing teams for the next several years.

Yesterday morning, at yet another autopsy after a Maple Leafs season, Burke was asked about the “Pittsburgh model” for building a hockey team, to which he responded, “Pittsburgh model, my ass.” Burke went on to suggest that the Pittsburgh model extended strictly to winning the Sidney Crosby Sweepstakes after the 2005 lockout. In short, he believes the Penguins got lucky in an ad hoc lottery. The truth is that while the Penguins were lucky enough to get the opportunity to draft the best player of his generation, the so-called Pittsburgh model entails much more than lucking out on Crosby.

The Penguins’ record this season without Crosby was 37-19-4. Clearly, Crosby’s absence did not suddenly turn the Penguins into a bottom feeder. They were still dynamite when he wasn’t playing. With Crosby, they are a great team, arguably the best in the NHL. Without Crosby, the Penguins remain a very good team, one of the best in the league. There is much more to the Pittsburgh core than Crosby.

The Pittsburgh model is best described as a commitment to the draft. The nucleus of the Penguins is comprised almost entirely of players they drafted. Marc-Andre Fleury was drafted first overall in 2003, Evgeni Malkin was drafted second overall in 2004, and Jordan Staal was picked second overall in 2006.

To suggest that the Pittsburgh model for success hinges on the selection of Crosby in 2005 is tantamount to wilful blindness. The Penguins procured many star players aside from him via the draft. One expects that Brian Burke knows he was off-base when he denigrated Pittsburgh’s blueprint. Perhaps Burke applied his trademark pomposity to the topic because he wished to provide distraction from the contrast between his quick fix strategy and the go slow philosophy applied in Pittsburgh and elsewhere around the NHL. One expects he didn’t wish to compare the success Pittsburgh has had by taking the long view with his own shorter term strategy that has been employed with the Maple Leafs.

Imagine you are looking to hire an architect to build a home. One architect says she/he will cut corners and take shortcuts so that the job gets done as soon as possible. The other architect warns you that the building process may take a long time but the house will be structurally sound and will look great when finished. You would probably think the first architect is bogus and you would hire the second one instead.

It is surely disconcerting to Leafs fans who realize that the man in charge of their team does not aspire to emulate one of the best teams in the game and moreover, to follow a blueprint that has a track record of success. What is more exciting? To root for the Maple Leafs, a team out of the postseason for the past seven years, or to cheer for the Oilers, a team that has missed the playoffs for a similar stretch of six seasons? The answer is obvious. The Oilers are supremely talented, exciting, and on the verge of success. The Leafs are not.

The Oilers, like the Penguins and others before them, have built their team via the draft. The philosophy that was yesterday referred to as the Pittsburgh model may one day be called the Edmonton model.

A GM tasked with rebuilding an NHL team may now look at the model laid out by Pittsburgh and Edmonton, compare it with the one at work in Toronto and say, “Toronto model, my ass.”

The decision to build through free agency and trades has produced a decidedly mediocre team in Toronto. The shortcuts espoused by Burke look more and more like short sightedness with each passing season. For the Maple Leafs there appears to be only one viable option moving forward. Burke must now retreat, fix the problems caused by his quick fix philosophy, and recommit to the draft.