Picture a scenario. Your local NHL team is playing a nationally-televised game. It’s on ESPN+, which you access through an app because you don’t have cable or satellite. You’re excited to watch it, but when you turn it on, you’re denied because of a TV blackout based on your location.

Another scenario. You live in Philadelphia and have purchased NHL.TV (formerly NHL Gamecenter Live) to watch your favorite team, the Tampa Bay Lightning, play. On this night, the Lightning are in town to take on the Philadelphia Flyers. You open NHL.TV, select the game, and you can’t watch it because you live in Philadelphia.

In both situations, the ability to watch hockey was hindered by the same thing: a blackout. No, not the blackouts that occur when you lose power because it’s summer and the electrical grid is overloaded. This type of blackout has to do with communication, specifically television and radio broadcasts and who is allowed to receive them.

What Are TV Blackouts?

A blackout of the communication variety is intentionally preventing certain audience members from receiving television or radio broadcasts. In sports, this manifests itself with games not airing due to regional sports networks or local channels having exclusive broadcasting rights. Three of America’s “Big Four” sports leagues – MLB, NHL, and NBA – currently has some form of blackout policy that restricts viewership.

The NHL and MLB, who both use digital properties started by MLB Advanced Media for streaming purposes, have similar blackout restrictions that are rooted in regional sports networks having exclusive broadcasting rights for the majority of games. For the NHL specifically, blackouts are present to allow regional sports networks to broadcast as many games as possible.

“Blackout restrictions exist to protect the local television telecasters of each NHL game in the local markets of the teams. Blackouts are not based on arena sell-outs. Keep in mind that blackout policies and restrictions are different for every sports package that your system may carry.” – The NHL Network’s defense of blackouts.

So if a game is on the NHL Network, it is being simulcast with the local broadcast. And, if that game involves the Los Angeles Kings and Minnesota Wild, as long as you live outside those markets, you can watch it. However, if you live within those markets, you are unable to watch it on the NHL Network and have to rely on the regional network for viewing.

Furthermore, games broadcast on ESPN or Sportsnet in Canada are subject to the same blackout restrictions. Although in 2013, Rogers reached an agreement that allows them to broadcast any game involving Canadian teams on Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday nationwide and without blackouts.

In the postseason, it’s a bit more complicated. Only a few years ago, regional networks and NBC, along with its properties, shared broadcasting rights in the first round. This led to blackouts similar to those in the regular season. However, starting with the 2017 Playoffs, NBC and regional networks shared rights and fans were able to watch the first round on either the local or national broadcast.

Markets? Regional Sports Networks?

So, by now, you may be asking yourself, “I get what TV markets are, but what determines them and how are they dispersed?” Fair question. For the most part, it’s simple. In general, a team is given a designated television market. The Detroit Red Wings have Michigan and the Vancouver Canucks have British Columbia. In some cases, a team’s market is bigger than a state or province and, instead, encompasses a region. The Boston Bruins’ market includes the New England states and the Dallas Stars have Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

Then there are the teams whose markets intersect, either because their fanbases stretch that far or because of multiple teams in one region. The Calgary Flames and Edmonton Oilers split Alberta, the Winnipeg Jets and Toronto Maple Leafs divide Western Ontario. The Buffalo Sabres, New York Rangers, New York Islanders, and New Jersey Devils all share New York state. Finally, in Southern California, both the Los Angeles Kings and Anaheim Ducks are covered.

Connecting Regional Networks to Markets

For the most part, each team’s market corresponds with a specific regional sports network. The Bruins are broadcast on NESN in the northeast, Canucks games can be found on Sportsnet Pacific, and Stars games are viewed via Bally Sports Southwest. In locations where multiple markets converge, fans are able to watch any of those teams’ games. In western Ontario, this means watching the Jets on TSN and the Maple Leafs on TSN and Sportsnet, and in New York, the Sabres, Rangers, Islanders, and Devils are all watched via the MSG Network.

But regardless of what market you live in and which regional network broadcasts your local team, if the NHL Network, ESPN, or Sportsnet is airing the game but doesn’t have exclusive broadcasting rights, national coverage will be blacked out in favor of regional coverage.

Who or What Is to Blame for Blackouts?

Getting to the bottom of who or what is to blame for television blackouts is a tricky proposition. There are several potential culprits. Is it the league or the teams? Is it national or regional networks? Could it be one of them, several of them, none of them, or all of them?

League vs. Team

The NHL’s culpability in the existence of blackouts lies in two areas. For one, they craft the league’s schedule each season. Specifically, Steve Hatze Petros, who determines the schedule. He takes into account arena availability, team preferences, and travel, while working within scheduling rules to build an 82-game regular season schedule for each team, totaling 1,312 games.

The league’s schedule doesn’t directly impact blackouts, but great matchups and teams with the largest fanbases are most likely to be picked up by national networks. And as we know, when games are broadcast nationally, blackouts occur. The league is also at fault because it negotiated the contracts that gave national broadcasting rights to networks.

According to Business Insider, the NHL earned $600 million in 2013 from television deals. In Canada, Rogers holds the rights, while ESPN and Turner split the contract in America. The previous NBC deal, which paid the NHL an average of $200 million per year through the 2021-22 season, was signed on April 19, 2011. In Canada, the NHL agreed to a 12-year, $5.2 billion deal in Nov. 2013 with Rogers, who owns Sportsnet. The deal pays the league roughly $430 million per year through the 2025-26 season. In the U.S. markets, Disney pays the league roughly $400 million per year, while Turner dishes out around $225 million. That deal runs through the 2027-28 season.

Each contract allows the network to broadcast and stream games across the network’s respective nation. In some cases, the national networks have exclusive rights to games, including “Wednesday Night Hockey” on ESPN and “Hockey Night in Canada” on Sportsnet, which overrides regional broadcasts. But in other cases, the national and regional broadcasts intersect and the national feed is blacked out in the teams’ markets. For the 2018-19 season, Rogers broadcasted more than 150 regular season games, while NBC and its properties aired 109 regular season games.

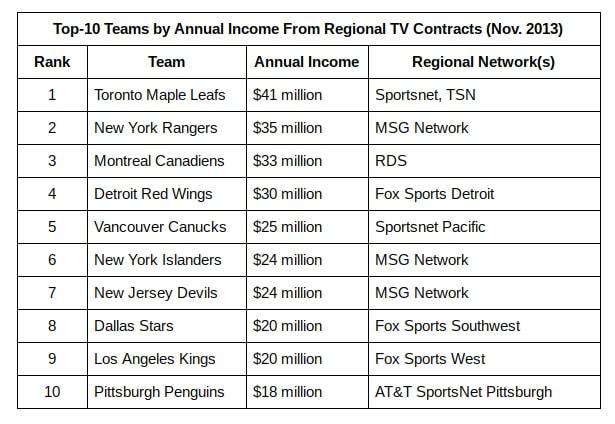

Team blame for TV blackouts is based on which regional sports network the team signs with to broadcast their games. These contracts, similar the league’s contracts with ESPN and Rogers, pays the team an annual fee to air games. While these contracts pale in comparison to other leagues, NHL franchises earn a substantial amount of money from local TV deals, a much larger amount than ticket or merchandise revenue.

As is expected, the teams with the most lucrative television deals are also some of the valuable franchises with the Maple Leafs, Rangers, and Canadiens leading the league.

National Vs. Regional Networks

ESPN and Rogers, because they own the national television rights in America and Canada, respectively, are allowed to choose which games they broadcast. This means covering games of popular teams and matchups that will draw fans. For example, a game involving the Bruins, Maple Leafs, or Pittsburgh Penguins is more likely to be picked up nationally than a game in which the Florida Panthers, Dallas Stars, or Carolina Hurricanes play.

But who can blame the networks for selecting games that will draw large audiences? They paid exorbitant amounts of money for the rights to air games and want to get as much of a return on their investments as possible. The issue is that if you’re a fan of a “popular” team and live in that team’s market, you will experience more blackouts than the average fan, unless you have access to a regional sports network. And with ESPN airing an ever-increasing number of games, the number of blackouts will likely follow suit.

When it comes to regional sports networks, there are several issues that create problems for hockey fans. For one, they are expensive. In general, regional networks charge several dollars per-household on a monthly basis to have access to content. For fans of one sport, in this case, hockey, this means you are presented with content beyond hockey, often programming you don’t watch.

The other issue is that regional networks control how many viewing options are available. Is streaming an option? Are you able to purchase a subscription as a standalone product rather than having a standard television package? These are important aspects because if a person is unable to afford traditional television but still wants to watch hockey, a regional network’s willingness to allow access impacts a fan’s viewing experience.

Something Else?

While all four elements discussed above have some culpability in the prevailing existence of blackouts, one other aspect remains most at fault. Despite it being over five decades old, the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 remains an impactful piece of legislature in America. That act, signed into law by John F. Kennedy, was a reaction to an earlier ruling that declared NFL franchises acting together to sign a league-wide television deal violated U.S. antitrust laws.

The initial ruling considered NFL franchises as separate businesses and working towards one television deal as a singular entity stifles competition. The Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 essentially repealed the earlier ruling by stating that sports franchises can pool their interests together to generate revenue as one unit.

“The Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 (SBA) exempted professional sports leagues from federal antitrust laws so that leagues could pool the individual team’s rights to telecast games. These licensing agreements—including television, radio, and digital—provide networks with the rights to broadcast games, and are a major revenue source for sports leagues.” (From “A Brief History Of The Drawn Out Sports Television And Streaming Blackouts Debacle,” SportsTechie 1/25/2016)

The article goes on to say that the act’s original intention was to protect sports leagues and their teams’ rights to generate revenue. However, all that it has done since is create and expand blackouts. Since that law went into effect there have been numerous attempts to repeal it, including the Furthering Access and Networks for Sports (FANS) Act.

The FANS Act was presented by Senators John McCain and Richard Blumenthal in Dec. 2015. The goal of the act was to amend the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 so that every game in every American professional sports league would be available in every market, either through the traditional format or via streaming. However, the bill was never passed.

Other Opposition

In 2012, a group of hockey fans filed a federal lawsuit against the NHL and television distributors. The lawsuit cited that the presence of blackouts in local markets despite subscribing to NHL.TV constituted a monopoly and therefore violated antitrust laws. The suit lasted over two years before the two sides reached a settlement. The settlement included the creation of single-team NHL.TV subscriptions at a reduced rate rather than having to subscribe to the entire league.

The plaintiffs in the suit agreed to the settlement when District Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that they couldn’t recover any money although she agreed that the league’s current set up is a monopoly. So while the lawsuit is viewed as a victory for those in opposition of blackouts, it didn’t go as far as many would have liked. The settlement didn’t address blackout rules, the issue that sparked the lawsuit in the first place.

Alternatives For Dealing With Blackouts

The issue with hockey blackouts is that there aren’t many legal options to get around them. Purchasing a cable or satellite package with the local regional sports network is the most straightforward option. Couple that with a league-wide subscription to NHL.TV and you’d have access to every NHL game.

Other than that, if you live inside your favorite team’s market and don’t want to pay for cable or satellite, the only other legal option is relocating outside your team’s market. That way you can either gain access to the Watch ESPN app to watch nationally-televised games or purchase a one-team NHL Gamecenter Live subscription to watch your team’s games. However, you’ll still face blackout restrictions when games are played in your local market.

Hopefully with the growing popularity of cord-cutting and separating from traditional media outlets, blackout restrictions will slacken and access to hockey games will be opened to all fans in all locations. Because right now, the NHL, the teams, and the networks may be growing profits at ever-increasing rates, but the product continues to suffer.