I stood in the lobby at the convention centre in downtown Toronto, looking around somewhat awestruck over the number of NHL legends and NHL people that were in the room.

My little digital recorder was tucked in the chest pocket of my dress shirt. Even though 2007 doesn’t seem like that long ago, it was long before we had cell phones that could record audio and video, connect to the internet, or take quality photos. I figured it would be a good night for interviews. The NHL and the Hockey Hall of Fame were involved in this function, so I knew the A-list hockey people would be out in full force.

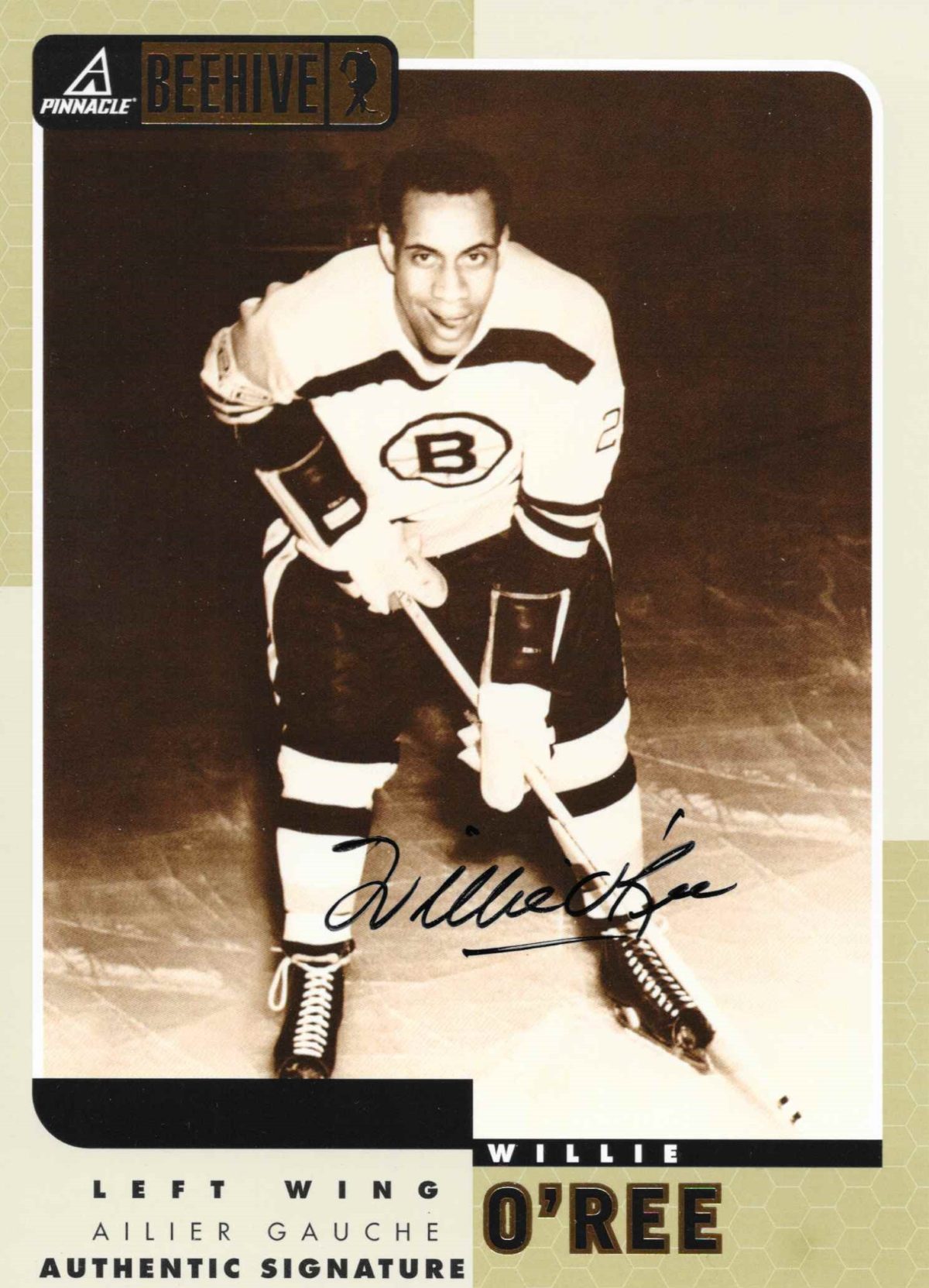

From across the room, I saw Willie O’Ree. I started to make my way over to him. I had developed a relationship with Willie 10 years earlier when I worked for Pinnacle. We made his first NHL hockey card during the 1997-98 season. He was always a wonderful person to deal with.

He gave me a warm smile and shook my hand. He is not a big guy, maybe 5’9” or 5’10” and about a buck-sixty. For a guy in his 70s, he was in tremendous shape. But shaking his hand was like handing my fingers and knuckles over to a chiropractor to be digitally remastered.

I reminded him who I was, and we explained pleasantries. I nonchalantly turned on my digital recorder, hoping for gold. Little did I know just how amazing the next 10 minutes of conversation would be.

Leo Boivin’s Rinkwide Pass

“I remember you telling me you’re from Eastern Ontario,” Willie said. Even though he was from Fredericton, he knew the area well. He spent the 1959-60 season with the Kingston Frontenacs of the Eastern Professional Hockey League. The next season saw him get his second of two career stints with the Boston Bruins, but for the rest of the 1960-61 and 1961-62 seasons, he played for the EPHL’s Ottawa-Hull Canadiens.

“I’m grew up in Prescott,” I told him, always proud of the little town of 5,000 people on the St. Lawrence River.

“Prescott,” he said with a smile. “That’s Leo Boivin’s hometown, right?”

“Yes sir, it is,” I told him. “Leo grew up with my father. The arena in Prescott is the Leo Boivin Community Centre.”

“Leo was such a great defenceman and great teammate,” Willie said. “He was known for that nasty hip check. And boy, I’ll tell you, if you didn’t keep your head up in practice, he’d take you out with it.”

Willie disappeared in thought for a moment, and then looked at me with a smile.

“You know, Leo set up my first goal in the NHL,” he said.

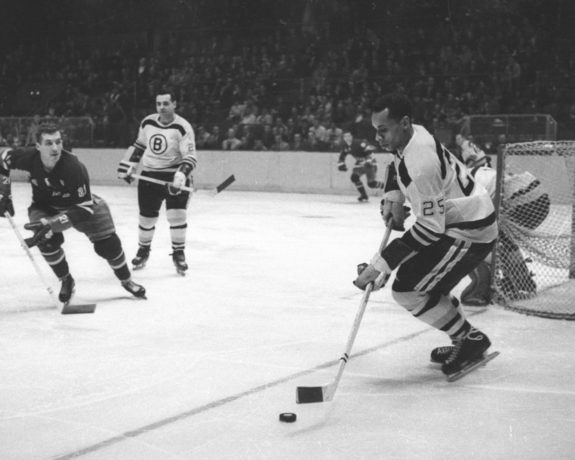

During the 1957-58 season, O’Ree was called up to the Bruins for two games to replace an injured player. He had been playing for the Quebec Aces of the Quebec Senior Hockey League, and he joined the Bruins in Montreal. He had been a big scorer in junior hockey and with the Aces.

In his second stint with the Bruins, O’Ree played in 43 games. He recorded his first points, scoring four goals and adding 10 assists.

Shoot Low, Willie!

“I will never forget my first goal,” he said. “It was New Year’s Day, January 1st, 1961, at the Boston Garden. We were playing the Montreal Canadiens. It was the second period.

“I’m playing left-wing, and I broke free from my check, and I put the afterburners on, and Leo Boivin hit me with a perfect pass. I didn’t have to break stride or anything. I went in and made a couple shifts on the defencemen. I got past Jean-Guy Talbot and Tom Johnson and had a clear path to the net.”

O’Ree, flying in toward the Montreal net at full speed, recalled some advice he was given before the game.

“Charlie Hodge was in net because Jacques Plante was hurt,” he said. “When we were warming up, Bronco Horvath had told me before the game, he said, ‘Willie, if you get a chance to go in on Hodge, shoot low. He’s weak on low shots. Don’t get the puck up where he can catch it.

“So when I went around the defencemen and went in on Hodge, all I could hear was this voice saying, ‘shoot the puck low, Willie. Shoot the puck low.’ So I shot the puck, maybe it was an inch or two off the ice, it was just a blisterin’. It hit the inside of the post and went in.

“That made it 3-1 for the Bruins, and then about seven minutes later Henri Richard, the Pocket Rocket, scored to make it 3-2, but the goal that I got stood up as the winning goal. I dove in the net, got the puck, and the fans gave me a standing ovation for over two minutes!”

Blind in One Eye

O’Ree could have scored more goals had it not been for a serious injury that he played through. While he played junior hockey for the Kitchener-Waterloo Canucks, he took a puck in the face and lost 95 per cent of the vision in his right eye. As a left-winger, it severely limited his effectiveness.

“While I played, the only person who knew I was blind in my right eye was my sister, and I swore her to secrecy,” O’Ree said. “I had a lot of success playing right wing. Even though it was my off wing, I could see the ice and the play much better. I didn’t dare say anything when I got to Boston because I was worried that if anyone found out, my career would be over.”

Leo Boivin talked about O’Ree in an interview in 2007.

“Willie was a great teammate, and the one thing I remember about him was how fast he was,” Boivin said. “He could really skate. We had no idea he was blind in one eye. Imagine how good he could have been if he could see out of both eyes.”

O’Ree loved to skate. He was on the ice as much as possible as a kid in Fredericton.

“I even skated to school as a kid,” O’Ree said. “My dad would take the garden hose and make a rink in the back yard. I was always on the ice as a child.”

Breaking the colour barrier, O’Ree said, was not a big deal at the time. While some refer to him as the Jackie Robinson of hockey, it took more than a generation for his accomplishments on the ice to be fully appreciated.

“I was the first Black player to play in the NHL, but I never really thought about that,” O’Ree said. “I loved hockey, and I wanted to play in the NHL. I wasn’t the best Black hockey player – that was Herb Carnegie. He was quite a bit older than me. He was a big star for the Quebec Aces, a few years before I was there, but he never got the opportunity to play in the NHL.”

Carnegie, at one point, was offered a minor league contract by the New York Rangers. That may have set him on a path to play in the NHL, but he was making more money in Quebec, so he turned them down.

“I always saw myself as a hockey player, not a black hockey player,” O’Ree said. “I used to tell myself that if the fans didn’t want to accept me for having the skills and the ability to play in the NHL, then that’s their tough luck. I knew I was going to face racial remarks, but I just let it go in one ear and out the other. I wasn’t going to deviate from my game and what I was going to accomplish.

“Because of that, I fought a lot. I won fights, I lost fights, but I still didn’t deviate from what I wanted to do. I wanted to represent the hockey club the best I could and play every game as if it were my last.”

While O’Ree was the first Black player in the NHL, it wasn’t until the 1970s when players like Mike Marson and Tony McKegney played in the NHL.

“When they played, they were considered good black hockey players,” O’Ree said. “It’s not like that anymore. Now, a good hockey player is just considered a good hockey player.”

The Boston Bruins were going to retire O’Ree’s jersey, number 22, this month. Because of the pandemic, they are going to wait until there are fans in the stands to honour him and celebrate his career. It has been rescheduled to Jan. 18, 2022.

“We hope and expect the change will enable us all to commemorate this moment in a way that matches the magnitude of Willie’s impact – in front of a TD Garden crowd packed with passionate Bruins fans, who can express their admiration and appreciation for Willie and create the meaningful moment he has earned throughout his incredible career,” read a statement issued by the NHL.

There will never be another 22 for the Boston Bruins.

And there will never be another Willie O’Ree.