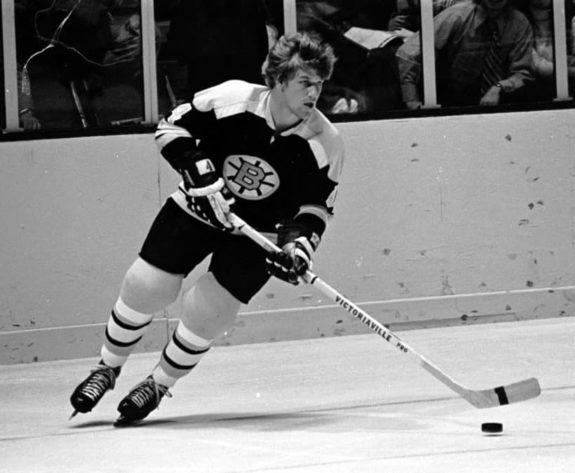

You’ve probably heard of Bobby Orr. Widely considered the best defenseman to ever play the game, and even considered by some the best player ever, the legendary No. 4 took his first strides in the NHL during the 1966-67 season — but, it was during Orr’s prime that he dominated the league. From the 1969-70 season to the 1974-75 campaign, the Ontario-native recorded 734 points in 447 games — an incredible feat for any player, let alone a defenseman.

But there is one campaign that seems to rise above the rest. During the Boston Bruins 1969-70 season, Orr netted a remarkable 33 goals and 87 assists in 76 games. He took home the Hart, Norris, Art Ross, and Conn Smythe Trophies and his first Stanley Cup. The Cup was a result of Orr’s most memorable moment — his flying goal.

It is unlikely that all of Orr’s awards can fit into a single trophy case. In total, No. 4 earned the 1966-67 Calder Trophy, three Hart Trophies, two Art Ross Trophies, two Conn Smythe Trophies and was named to nine all-star teams. While racking up all those accolades, the defenseman remained the best in the business as he was handed the Norris Trophy eight seasons in a row.

Orr’s regular season totals rest at 270 goals and 645 assists (915 points) in just 657 games. His plus-minus rating for those games resides at a whopping plus-582. During the postseason the defenseman went on to produce 26 goals and 66 assists (92 points) in 74 playoff appearances.

Orr Takes Flight

It is the most recognizable highlight in Boston sports history. The goal ranks up there with memories of the Boston Red Sox’s 2004 World Series championship, the New England Patriots’ first Super Bowl win, and the Boston Celtics’ incredible streak of eight consecutive championships from 1959 to 1966.

But Orr’s goal goes beyond winning the Stanley Cup. It was poetic that the Bruins’ best player potted the best goal in the franchise’s history. The game took place on May 10, 1970 — Mother’s Day. Play-by-play announcer Dan Kelly’s call of the final moments of Game 4 will give you goosebumps even to this day.

A big party started in Boston Garden. Orr, still on the ice after being tripped by St. Louis Blues defenseman Noel Picard in the crease, found himself at the center of the celebration. According to Orr, though, his flight through the air was by choice.

“As I went across, Glenn’s legs opened. I looked back, and I saw it go in, so I jumped.”

Bobby Orr, ‘The Goal: Bobby Orr and the Most Famous Goal in Stanley Cup History’ by Andrew Podnieks

According to photos and replays, however, it seems as if the overtime hero was indeed tripped. Perhaps Orr simply wanted to avoid embarrassing a fellow defenseman. Maybe he didn’t want the media to run rampant with such a small footnote — after all, the Bruins had just clinched the franchise’s first championship since 1941.

No. 4 started celebrating just before being tripped, resulting in one of the most iconic photos in hockey. The photo was snapped by photographer Ray Lussier as Orr flew through the air like a Superman, his arms outstretched and an ecstatic expression on his face. (from ‘Former Haverhill newsman captured Orr’s famous ‘flight’,’ Eagle-Tribune, 05/11/2010) He was forever remembered as a superhero in the eyes of Bruins fans. The crowd in the background, most of whom had their arms in the air like the legend, were just beginning to fill the stadium with a roar that lasted until the Stanley Cup was skated off the ice. It was the moment Orr realized he was a champion, captured and engraved in history.

1970 Stanley Cup Final

Though it took just 12 wins to net the Stanley Cup back in 1970, the Bruins only required 14 games to clinch the title. They lost just two games — both to the New York Rangers during the first round in Games 4 and 5 — before winning 10 straight en route to the championship. Phil Esposito led the team with 13 goals and 14 assists, followed by none other than Orr who tallied nine goals and 11 helpers.

After sweeping the Chicago Black Hawks in the second round, the Bruins went on to face the Blues. During Games 1 and 2 in St. Louis, Boston outscored their opponent 12-3. They increased that margin to a score of 16-4 during Game 3 as the teams headed into what would be the final matchup of the 1970 NHL Playoffs.

Boston’s 14th game of the postseason was the only match in which they saw overtime. It was just the third time they were forced to take a matchup by one goal during their historic playoff run. Red Berenson, Gary Sabourin, and Larry Keenan were credited for the three Blues goals during Game 4. Meanwhile, Rick Smith, Esposito, and John Bucyk netted three goals for Boston in order to send the game into overtime.

During the 40-second extra period, the Blues could barely keep the puck out of their own zone, opting to dump the puck down to Boston’s blue line. Orr picked up the loose puck, skated it to the red line and dumped it back into St. Louis’ zone. Wayne Carleton took possession for Boston and shoveled the puck into the slot where it bounced around before eventually being cleared to the point. Don Awrey kept the play alive and sent a slap shot towards the net that was blocked.

Derek Sanderson picked up the ricochet and took his own slap shot which “whistled wide” according to Kelly. Both teams fought for possession along the left boards before the puck squeaked out and a streaking Sanderson took a shot from the left face-off circle which also missed the cage. He then circled behind the net and stood patiently to the right of the goal.

The puck bounced off the right boards and Orr stopped short, corralling the puck with his skate. St. Louis’ Keenan took a one-handed chop at the puck to no avail as the Bruins defenseman had already transitioned it to his stick blade. “If it had gone by me, it’s a two-on-one,” said Orr. “So I got a little lucky there.” Blues’ defenseman Jean-Guy Talbot also took a one-handed swipe at the puck as Orr skated it to the corner, proceeding to dish it to Sanderson who was still waiting below the goal line.

Then, in Orr’s own words, “Derek gave me a great pass and when I got the pass I was moving across. As I skated across, Glenn had to move across the crease and had to open his pads a little. I was really trying to get the puck on net, and I did.”

And you know the rest: Orr soared through the air in ecstasy having just won his first Stanley Cup. He would go on to win it again with many of the same teammates in 1972, but there is something special about a player’s first championship — especially when it is won in such a dramatic fashion.

Orr’s Lasting Impact

Not only did Orr’s flying goal net the Bruins their first Stanley Cup since 1941, but it changed the landscape of hockey in New England forever. When the Bruins won the Cup in 1970, nearly every kid in the area wanted to lace them up wearing No. 4. Just like the city’s hero, hockey itself took flight in Boston.

You may also like:

- How the Bruins Stack Up in the Atlantic Division After Free Agency

- Bruins’ Marchand on Cusp of Historic 1,000-Point Milestone

- Bruins’ Opening Night Forward Projections

- 4 Bruins Storylines to Follow in 2024-25

- 9 NHL Teams That Missed in Free Agency

The sports spectrum in New England was dominated by basketball at the time, as the Celtics had already brought home 11 championships by the time 1970 rolled around. But Orr’s most memorable moment, in union with the remainder of his storied career, brought hockey back to the forefront in the city. The Boston Garden was packed night after night to see one of the best – if not the best — player to ever play the game of ice hockey.

Orr’s goal didn’t just put an end to a 29-year Stanley Cup drought in Boston. It did far more for the city than that. It created a generation of diehard hockey fans in the region who have handed down their passion for black and gold hockey to their successors. Many Bruins fans who weren’t alive to witness Orr’s most famous moment were surely told about it with the sense of an old folk tale — though this one is 100-percent true.

* originally published in July 2018