Back in the early 1950s, Gordie Howe and Ted Lindsay were two-thirds of the Production Line on the Stanley Cup champion Detroit Red Wings. Howe was arguably the best player in professional hockey and Lindsay, among the top five.

The start of every year meant it was contract talk time. Howe wanted a raise. Lindsay did too. They certainly had earned it.

Howe suggested they approach notorious Detroit GM Jack Adams and negotiate together.

It was a novel concept. It gave them leverage. In Adams’ office, two of hockey’s best and toughest players made their pitch.

“Get out!” said Adams.

So ended hockey’s first double holdout.

The Great Holdout

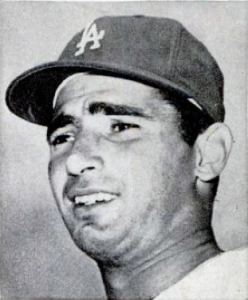

In 1966, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Don Drysdale joined teammate and, far and away, the best pitcher in Major League Baseball, Sandy Koufax, in what is known as either the Great Holdout or the Double Holdout. They approached Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi together and said, ‘Sign us both on our terms or you’ll get neither of us.’

Unlike Adams’ reaction, Bavasi was caught entirely by surprise and agreed to talk things over.

Initially, Koufax and Drysdale wanted a three year contract worth $1 million, or $166,000 each for three years. In 1965, Drysdale made $80,000 and Koufax, $85,000, so this represented a substantial raise demand.

Additionally, one year contracts were the norm. The idea that a player should have anything beyond one year struck many baseball people as absurd. As Bavasi put it, athletes sell their physical ability, and nobody can possibly guarantee that ability in three years’ time.

Bavasi flatly rejected the offer, so the two pitchers made a new one, what would have been the first front-loaded contract in sports: $200,000 for both 1966 and 1967, and $100,000 for 1968.

Bavasi said no.

Negotiations continued until the very last moment in the spring of 1966. Finally, the two sides agreed on one year contracts for each player, with Drysdale receiving a $30,000 raise, up to $110,000 and Koufax, $40,000, up to $125,000. Instantly they represented the biggest raises in the history of baseball.

Bavasi said that it worked for two reasons: one, they caught the Dodgers by surprise, and two, because it involved the game’s greatest pitcher.

Enter Bobby Orr

Of course this is a tenuous connection and in fact the similarities are few, separated as they are by over a decade. As for why Howe and Lindsay didn’t put up a fight, we can only speculate. But one important difference between the two Double Holdouts can be found in a man named Bill Hayes. Hayes was Sandy Koufax’s lawyer and he acted as the agent for both Drysdale and Koufax. Despite that role, Bavasi was adamant that not once during those negotiations did he ever exchange a single word with Hayes, and he had a very good reason for not doing so:

If I did that, I opened the door to more trouble than baseball ever dreamed in its worst nightmares. If I gave in and began negotiating baseball contracts through an agent, then I set a precedent that’s going to bring awful pain to general managers for years to come, because every salary negotiation with every humpty-dumpty fourth-string catcher is going to run into months of dickering.

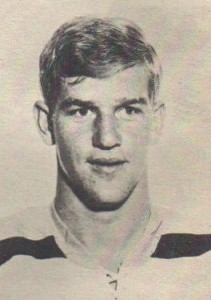

In September 1966, five months after Drysdale and Koufax signed, Toronto lawyer Alan Eagleson had Boston Bruins GM Hap Emms over a barrel in negotiations regarding young Bobby Orr’s first NHL contract. In securing (relatively) big money for Orr, Eagleson ushered in the era of agents negotiating contracts.

What Buzzie Bavasi had done for pro sports owners in April, Hap Emms forever undid for them in September.

At the time, Orr expressed some concern that hockey’s rank-and-file would be headhunting him for holding out and earning such a high salary before playing a single game, but Orr wasn’t all that worried.

“I think I did something that will be good for all the players someday,” he said. “I just stood up, eh? I don’t think they can mind that.”

Sources:

Bavasi, Buzzie and Olsen, Jack. “The Great Holdout.” Sports Illustrated, 15 May 1967

Deford, Frank. “A High Price for Fresh Northern Ice.” Sports Illustrated, 17 October 1966

Swift EM. “And On And On And…” Sports Illustrated, 17 January 1980