Warriors on the Ice: Hockey’s Toughest Talk

by Brian D’Ambrosio (2013: Jabberwocky Press. Kindle Edition. Pp. 229. $8.70.)

As human beings, we’re taught that every story has two sides – that people see things differently. In hockey, the ‘story’ that has surfaced and remained at the forefront for the sports’ discussions is the issue of fighting. Should it be allowed in the National Hockey League?

The league continues to institute rules in the hopes of reducing what some argue is an unnecessary part of the game – the instigator rule, the late-in-the-game coaches fine, and most recently the rule that penalizes players for removing their helmets.

We all hear the arguments from both sides – that fighting is a way of players self-policing their game, while others point out the long-term affects of a bare-knuckle brouhaha. But every once and a while, we witness incidents that force us to hold our breath and question fighting’s place in hockey all over again.

Brian D’Ambrosio’s book, Warriors on the Ice: Hockey’s Toughest Talk focuses on this long-debated subject. He uses interviews with some of the game’s all-time greatest tough guys to open up the conversation of how the role has changed over time – including references to recent incidents.

October 1, 2013

Throughout his book, D’Ambrosio and his interview subjects make reference to an incident that occurred on opening night of the 2013-14 season in Montreal. During a fight between Maple Leafs’ enforcer Colton Orr and Canadiens’ big guy George Parros, Parros was tugged down awkwardly by a falling Orr. Hitting his face on the ice, Parros was knocked unconscious and would miss a significant amount of time following that fight.

“It’s terrible to see a guy fall and hit his head. It’s completely accidental. You never want to see a guy go down like that, but I think it would change the game if you took fighting out, with guys taking liberties and things like that. It’s kind of like when you took the instigator out: You started to get the choppiness and more liberties taken, because you can’t go out and police it yourselves.”

– Derek Dorsett, regarding Parros-Orr incident and fighting in hockey

However, it’s not the first time the discussion has arisen. It certainly won’t be the last. As many of D’Ambrosio’s subjects suggest, rules are being put in place to shorten the existence of fighting in the game – or at least make it harder for those looking to participate in that sort of on-ice activity.

But what do the players think of this? What do those playing the game believe should happen to the skill set that put guy like Joey Kocur, Tie Domi and others on the map?

“In a 2012 poll by CBC and the NHL players’ association, 98 percent of players said they did not believe fighting should be completely banned. Even after the Parros incident, there has not been any player call for drastic change.”

– Brian D’Ambrosio in Warriors on the Ice

The problem for many is not the fighting itself, but how the role of the on-ice tough guy has changed. Warriors on the Ice is not just about former fighters. It’s about their struggle to stay afloat in the NHL and the evolution of the tough guy role.

In fact, it was about how one tough guy changed the role forever and how it’s never been the same since the days of the legend Bob Probert – a tough guy by trade with the ability to play hockey. And yet, the issues don’t just surround the players on the ice. As D’Ambrosio alludes to in his book, it’s the players’ health both physically and mentally that continue to be debated.

The League, The Role, And Player’s Health

Mental health has been under the microscope of hockey’s leaders for a long time. But it’s become more apparent and more discussed over the past decade. Unfortunately, hockey’s seen the passing of guys like Wade Belak, Rick Rypien, and Derek Boogaard in the past few years which has put the spotlight on the game’s enforcers.

D’Ambrosio subtly examines some of the game’s feistier players from the past using his interviews as ways to look at how these players are handling life after hockey. Is it the fighting that causes these bouts with depression? Or are there players in all roles who struggle with the silent disease?

“What troubles me is that some people say that fighting was the cause of these deaths – Wade Belak, Rick Rypien – and that it was related to their job as a hockey player. Most tough guys lead normal lives, and I think that they would have had problems whether or not they worked at a gas station or were CEOs. I don’t believe it was hockey that did it to them. All players face pressure, even guys who score face pressure.”

– Tim Hunter, regarding suspicious deaths of NHL tough guys

But it’s a concern that D’Ambrosio raises throughout his book and with each of the thirty former players that he interviews. Some of them talk about the anxiety they felt going into a game – the need to get their nightly fight out of the way. Others mentioned the need to stand up for their smaller teammates. But some of the players, like now-entrepreneur Ken Belanger simply pointed out that it was a job. It was a chance to play in the NHL and a way to stay in the show.

“My son is nine, and he is just at the age when it’s starting to come up. I’ve never showed him the fighting, but I’ll tell him and his buddies that it was my job. You build businesses around roles, and if you don’t do that role, you are out. If I was sent down to the minors, I’d have to also explain that to my kids.”

– Ken Belanger, on playing a role in the NHL

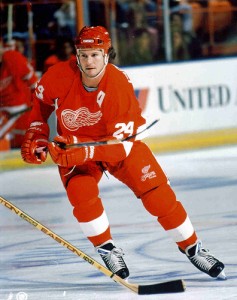

Bob Probert: Warrior on the Ice

The most noticeable recurring theme in D’Ambrosio’s book – the one that each player mentioned at some point – was the role of Bob Probert in the game of hockey. More specifically, they talked about his ability to play the game, engage others, and how the role of the tough guy has never quite been the same. In fact, it’s D’Ambrosio himself that suggests that Probert could be the last great warrior on the ice.

His uncanny ability to agitate, while being a big time player changed forever what the role was. And it’s never been the same. He was described in different ways by different players, but throughout Warriors on the Ice each player spoke of the legend with the same level of respect. He could score right after coming out of the box following a fight. He was the legend around the league – the guy every tough guy wanted to fight.

“I looked up to him. I was in awe of his career and all of the things he’d done.”

– Gordie Dwyer, on fighting Probert

D’Ambrosio uses thirty interviews of thirty former enforcers to detail how the role of the tough guy changed – with the addition of staged fighting and lack of hockey ability. The longevity of these role players hasn’t changed, so long as they can play the game. Probert lasted because he could score. Tim Hunter remained in the NHL because he knew how to change his game to remain there. Today, the best enforcer is Shawn Thornton. The length of his career is just proof of that.

Warriors on the Ice brings the focus back on the role of the tough guy in the NHL and whether there’s a place for them. D’Ambrosio gives perspective to the debate using interviews from some of the game’s best – including Riley Cote, Tim Hunter, Rocky Thompson, and Tony Twist among others. They deliver personal accounts in this narrative-driven book.

It’s not a book that’s meant to solve any debate, but bring light to questions regarding the hockey’s harder role. Each player explains why they did and how playing that role made the feel during and after their career in this eye-opening account of thirty NHL careers – short and long.

Questions or comments? You can follow Andrew on Twitter at @AndrewGForbes or on Google+.