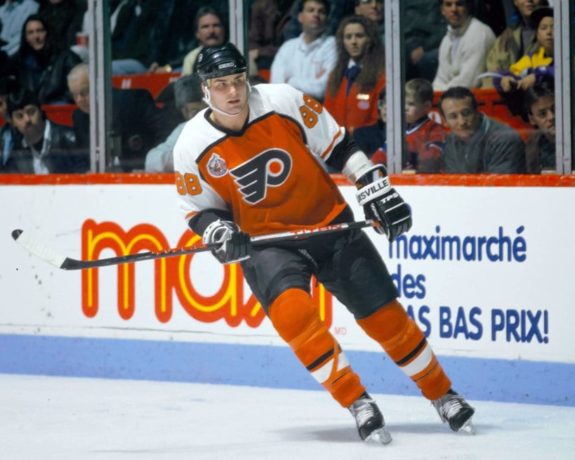

Everyone has heard of Eric Lindros. He was the first overall pick in 1991 and started his career with a bang, refusing to sign with the Quebec Nordiques, the team that drafted him. That forced them to trade him to the Philadelphia Flyers, where he went on to be one of the biggest stars of the 1990s. Although concussions and other injuries derailed his career, he still earned a place in the Hall of Fame in 2016.

However, far fewer fans have heard of his younger brother, Brett. At one time, they were mentioned in the same sentence, with a (very) select few proposing that the younger Lindros could even be better than his All-Star sibling. But then he disappeared into obscurity, earning the infamous title of the draft bust. Yet that title is undeserved, especially in the years following Eric’s induction into the Hall of Fame. Brett’s career had an eerily similar trajectory to his older brother, with the major difference being that it ended before it even started.

Everyone Wanted the Next Lindros

The NHL was a very different league in the 1990s than it is today. Players were getting much bigger than they had been in the 1970s and 1980s, but they were also more skilled than ever before, resulting in a much bigger emphasis on defensive skills. Suddenly, the rink felt a lot smaller, which gave rise to a new strategy that prioritized shutting down opponents before they could even enter the offensive zone. The high-flying game that had up to eight goals a game on average slowed down to a crawl, dropping to over five goals a game in 1997-98.

To succeed in that landscape, players needed to be big, powerful, and skilled, and in 1994, few were better than Brett Lindros. In his first two seasons with the Ontario Hockey League’s (OHL) Kingston Frontenacs, he scored 15 goals and 32 points in 45 games while racking up over 250 penalty minutes. He also played on the touring Team Canada and was the youngest member of the team in both 1992-93 and 1993-94. During those two seasons, he put up eight goals, 21 points, and 151 penalty minutes over 55 games.

It was clear that Lindros had the potential to become a dominant NHL player. While he wasn’t as gifted offensively as his older brother, he certainly made his presence known on the ice, and NHL teams started to take notice as they prepared for the 1994 NHL Draft. The Los Angeles Kings and Tampa Bay Lightning, who owned the seventh and eighth picks, had shown significant interest in the burgeoning power forward, but Lindros made it clear that he had no interest in joining either team due to their place in the standings. Rather than put themselves in a difficult position, they decided to pass on him.

That left Lindros ripe for the taking ninth overall, but the Nordiques, who had acquired the pick in the original Lindros deal, had no desire to go through that again. That piqued the interest of the Toronto Maple Leafs general manager Cliff Fletcher, who had just received the 10th overall pick after trading away long-time fan favourite Wendel Clark to the Nordiques just moments before. He had aggressively pursued Eric two years earlier but had come up short, so he made a pitch to Quebec.

Unfortunately for the Leafs, the Nordiques had other plans, sending their pick and Ron Sutter to the New York Islanders for Uwe Krupp and the 12th overall pick, leaving Toronto on the outside looking in once again. But Islanders general manager Don Maloney had big plans for their new pick, saying, “We finished the season last year on such a down note that we were looking for a new identity, a new beginning. He was a symbol of what we lacked: some size, some toughness.” (from “Lindros building his own identity,” Tampa Bay Times – 28/01/95).

Brett Lindros’ Early Dominance

After the draft, the Islanders were eager to bring him aboard, signing him to a five-year, $7.5 million deal before he even played a game, but the 1994-95 lockout prevented them from bringing him aboard immediately. So, instead, Lindros returned to the Frontenacs, where he went on a tear to start 1994-95. In 26 games, he scored a career-high 24 goals and 47 points, proving to everyone that he wasn’t just some thug. It was also enough proof to show that he was far too good for junior, and at 6-foot-4 and 215 pounds, few players could stop him.

Finally, on Jan 21, the Islanders were able to call up their top prospect and see what he could do. The hype for his arrival was somewhat muted, however, as many assumed he would have a minimal impact in his first season. “I don’t think he’ll make a big difference this year,” said Maple Leafs scout Pierre Page. “But he belongs here, and down the road, I can see him scoring 30, 35 goals and being a tremendous physical presence. And he’ll be a big draw.”

Related – Rick DiPietro: A Promising Career Cut Short

That’s exactly what the Islanders needed — a player who could put fans in seats and give the team a personality. Thankfully, Lindros took no time establishing that identity. Fifteen seconds into his first game, he flattened Florida Panthers defenceman, Geoff Smith. Three nights later, he faced off against his older brother and made the highlight reel again with a big hit.

That was all the Islanders needed to convince them they had found their next Clark Gillies, and Chris Gratton, his former OHL teammate, concurred, saying, “He’s an all-around package. With a player of his size, you take notice, but a lot of people don’t realize he has pretty good hands, too. The thing that caught everybody’s eye is the way he can dominate a game.”(from “Lindros building his own identity,” Tampa Bay Times, 28/01/95).

The comparisons were a bit extreme, of course, but the Islanders desperately needed someone they could build their franchise around, and Lindros promised to be that guy. He still had a long way to go in his development, but in the future, there was no question that he could have a similar impact to his brother on the defensive side of the game. This player could be the face of the franchise, and if he could add a bit of scoring, the Islanders could become unstoppable.

Concussions End a Promising Career

There were several drawbacks to the physical, clutch-and-grab style of hockey popular in the mid-1990s. Offence dried up to record lows not seen since the 1950s when there were only six teams, and it took a full-year lockout to sort out. But the most devastating impact was the increased number of concussions. Eric Lindros became the unofficial spokesman for concussion awareness after experiencing several throughout his career, many of which came due to his physical style of play, destroying his potential and forcing him to retire in 2007. Many others from that era have similar stories, but few are as drastic as his younger brother, Brett.

Brett finished his first season with the Islanders with a goal, four points, and 100 penalty minutes in 33 games while playing primarily on the second line. But he also sustained a concussion that season after a fight with Pittsburgh Penguins defenceman Francois Leroux that caused him to miss eight games. The event didn’t receive much attention; after all, he hadn’t missed any OHL games due to injury.

However, Lindros was not fully aware at the time that he had sustained at least five concussions in junior that went undiagnosed and untreated, creating a ticking time bomb inside his head. He started his sophomore season strong, putting up three points in 18 games, but then missed two games after an incident against the Kings on Nov. 16. When he returned on Nov. 24, he sustained another concussion, forcing him out of the rest of the season. That last concussion, reportedly his eighth or ninth of his career, was the final nail in the coffin; on May 1, 1996, the Islanders announced that their star prospect had been forced into early retirement due to injury. Lindros was just 20 years old.

“What was scary for me was each time it took longer to resolve — my last concussion before my 20th birthday took eight or nine weeks. Sometimes I had memory loss on the bench.”

Brett Lindros to the New York Times

Soon after his retirement, the Islanders claimed that they were not responsible for the remainder of his contract because he had not disclosed his previous concussions. That forced the two sides into a legal dispute that wasn’t settled until 1998, with Brett receiving the rest of the $7.5 million he was owed (from “Islanders Settle With B. Lindros,” Washington Post, 06/01/1998). He later went on to host segments for the NHLPA in the early 2000s and has since become successful in the investment industry.

Lindros’ Legacy Leads to Meaningful Change

When Eric was inducted into the Hall of Fame, he called up his brother to share the moment with him, saying, “I want to close this chapter of my life with you beside me.” It was a touching moment that reminded everyone in attendance how far the league had come since their careers ended. For years, the league has downplayed the severity of concussions, but after seeing the devastating effects it can have on former players like Wade Belak and Derek Boogaard, attitudes have changed around those who played through the dead puck era.

Therefore, if Eric can be a Hall of Famer, Brett doesn’t deserve to be called a bust. Both players had the talent to be effective NHL players, but the younger brother’s career was over before it began. In fact, Eric was more aware of the effects of concussions because of Brett, leading him to fight for a better diagnosis. Brett may be a footnote in hockey history, but his impact has spread throughout the sport.