On Friday night, Marc Bergevin will make the most important draft pick of his career as general manager of the Montreal Canadiens. Some would argue that already happened when he selected Alex Galchenyuk in 2012, his first year on the job. That said, people are more likely to forgive a rookie mistake than one made by someone with experience. After six years, and with the highest first-round pick he’s had since then, he is expected to bring a player to the team who will lift the Habs out of their slump and remind fans of the glorious history of their franchise.

It won’t be the first time a Hab executive will choose a player that will define his career. Fans old enough to remember the famous 1980 draft still speak with disdain about Irving Grundman, the Canadiens GM who chose Regina Pats’ star Doug Wickenheiser over local hero Denis Savard as the first pick that year. In retrospect, Wickenheiser was the more dominant player in juniors; if anything the Habs did not manage him well and like many talented kids, having to spend time in the press box instead of getting ice time may have ruined his confidence early on.

In 2005, the Canadiens had the fifth overall pick, their highest since that fateful 1980 draft. Instead of a skater, Bob Gainey shocked the hockey world by choosing goaltender Carey Price. The Habs already had a strong goalie in Jose Theodore but Gainey was unwittingly prophetic, as Theodore’s best years would prove to be behind him.

Besides, it wasn’t unheard of to select a goaltender with a high draft pick. Future Hab goaltender Al Montoya had been selected sixth by the New York Rangers the previous year, and Marc-Andre Fleury was the first pick overall for the Pittsburgh Penguins in 2003.

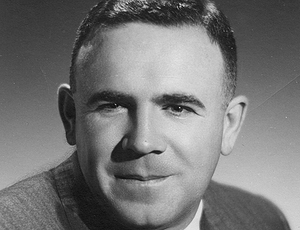

If we go back to the year I was born, 1964, a newly-hired Habs GM would also set the tone for much of his career with one pick. He was not unknown to the organization, having virtually developed their farm system over the previous decade-and-a-half, but Sam Pollock, known as “Trader Sam”, would begin a legacy of robbing other general managers by scenting young talent and exchanging them for veterans or prospects, propelling his team to another decade of dominance.

1964: The Bruins Reach Rock Bottom

The 1963-64 Boston Bruins were far from the class of the six-team NHL. In fact, they finished last in the league, winning only 18 of 70 games and scoring 170 goals, the lowest total in the league. Eddie Johnston, their stalwart goaltender and possibly their best player, was in goal for every minute of every game, becoming the last NHL goalie to accomplish this feat. Oddly enough, the Canadiens organization had given up on Johnston five years earlier, sending him to the Chicago Blackhawks, who would, in turn, deal him to the Bruins.

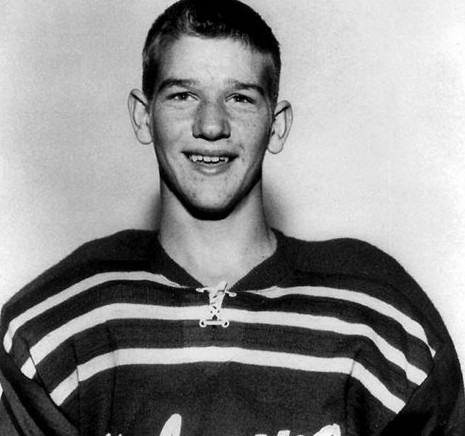

Perhaps sensing that Johnston needed the occasional rest, the Bruins chose a young goalie from the suburbs of Toronto as their third pick in the June amateur draft, held that year in Montreal.

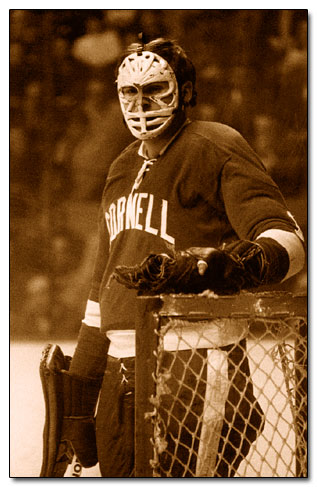

Ken Dryden was a cerebral kid, only sixteen, but already intent on pursuing a higher education. He would forsake the junior hockey system for college, attending Cornell University as a history major, while honing his skills playing varsity hockey. With Cornell, he would set numerous goaltending records and lead his team to the NCAA hockey championship in 1967.

Pollock Makes His Move

Two weeks after the draft, the Bruins dealt the rights to Dryden to the Canadiens for two coveted prospects, Guy Allen, a big defenseman, and Paul Reid, a forward. The Bruins also sent an earlier draft pick, Alex Campbell, to the Habs. At the time, college players were a rarity in the NHL and most did not transition well to the pros.

As it turned out, neither Allen, Reid, nor Campbell played even a minute in the NHL. The Bruins weren’t shattered; a teenager they selected in 1962 would soon rewrite the book on playing defense and become the blueprint for every mobile defenseman who would succeed him.

Naturally, the Habs were also interested in Bobby Orr but the Bruins convinced the young phenom to sign with them, even sponsoring his hockey team in Parry Sound, Ontario.

An Inconsequential Trade

While Dryden was in upstate New York, making saves and studying war and revolution, the Canadiens spent the rest of the 1960s winning four Stanley Cups in five years, beginning with 1965, their first Cup win since 1960 under their new general manager. Goaltending duties were shared competently between Charlie Hodge, Gump Worsley, and Rogatien Vachon, so little thought was given to the tall kid they traded for in 1964.

Vachon inherited the #1 job in 1969-70, the year the Habs were denied a playoff spot for the first time in two decades. The following year looked more promising; the team was in third place through most of the winter, comfortably ahead of the Toronto Maple Leafs who held on to the final playoff spot. After he was beaten badly by the Los Angeles Kings in early February, backup goaltender Phil Myre was relegated to the bench, while Vachon played a long streak of consecutive games.

Dryden Makes His NHL Debut

On March 8, the Canadiens decided to bring up a goaltender to help Vachon. Dryden, now a law student at McGill University, was juggling time between legal books and playing for the Habs’ AHL affiliate, the Montreal Voyageurs.

Dryden gave Vachon the break he needed, starting six games at the end of the regular season and winning them all while posting a 1,65 goals-against average (GAA). In the playoffs, the Habs faced the seemingly unstoppable Bruins; they had broken team and NHL records and seemed like an easy bet to repeat as Stanley Cup champions. Dryden was a surprise starter and contributed heavily to upsetting the team that once drafted him, even beating Eddie Johnston, the goaltender he was originally drafted to replace.

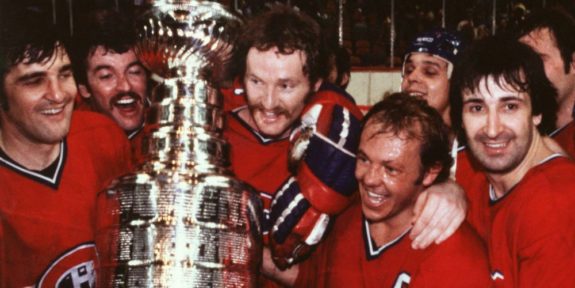

Dryden’s Legacy Was Also Pollock’s

The remainder of the decade belonged to Dryden. After their first-round victory, his Conn Smythe-winning performance led the Habs to an unanticipated Stanley Cup. He would win five more Cups in seven years, taking a year off to article at a law firm after a contract dispute before the 1973-74 season. There would be more victories against the Bruins, and more opportunities to showcase the brilliance of his general manager, who assembled a team of stars around him through crafty trades, and wise draft choices.

In 1978 Pollock retired, followed by Dryden a year later. The Habs won only two Cups in the next 40 years, as seven general managers attempted in vain to replicate the successes of their predecessor.

Sam Pollock’s small trade at the beginning of his career seemed insignificant at the time. Even Ken Dryden only found out he was drafted by the Bruins in 1974. However, his decision to use his hockey instincts and knowledge of young talent, coupled with an uncanny ability to see into the future, proved to be the gold standard he would follow for his entire career as the NHL’s greatest GM.