On a chilly late October evening outside the doors of the Eric Maclean Center for the Performing Arts on the campus of Loyola High School in Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (NDG), a line of people is starting to form. Some of them are wearing now ill-fitting Montreal Canadiens hockey jerseys emblazoned with the names and numbers of hockey legends such as Lafleur, Richard and Béliveau. Others are carrying pieces of memorabilia crested with the famous logo of the Habs – magazines, banners, flags, even parts of seats from the Montreal Forum. A wide range of age groups are represented in this growing group of die-hard hockey fans.

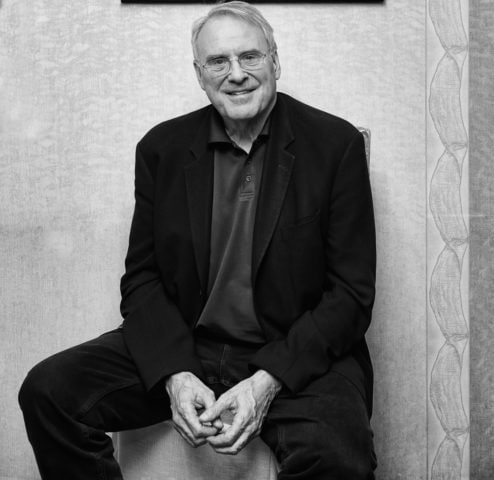

There is a palpable sense of excitement among these early arrivals hoping for a signature on their prized possessions. But for most of the people braving the chill of this windy fall evening, they are here to listen to two hockey legends. In a few hours they will be riveted by the stories of two icons of the sport speaking about a unique hockey life, that of Scotty Bowman as described by Habs Hall of Fame goalie, Ken Dryden.

As part of a tour promoting Dryden’s new book entitled Scotty – A Hockey Life Like No Other (published by McLelland & Stewart), the two hockey legends are preparing for an evening in Montreal’s west end to share with fans, young and old, the highlights of the unique hockey journey of one of the most successful coaches in all of professional sports.

A Book Dryden Needed to Write

This is Dryden’s fourth book where hockey is the main topic. He had been thinking about writing Bowman’s story for close to ten years. Ironically, he was also hoping that another author would take up the project. However, when no one did, he took on the challenge. He contacted his former coach with whom he, along with players like Guy Lafleur, Steve Shutt, Jacques Lemaire, Larry Robinson, Serge Savard, Guy Lapointe and others, dominated the NHL in the latter part of the 1970s.

The book is not a compendium of anecdotes and stories from an old coach. That is not what Dryden wanted to do in telling Bowman’s unique story. He wanted to put his former coach in the position where he has always been the most comfortable – behind a bench.

I needed to write this book for very different reasons. Scotty and I shared a time together – the most important of my hockey life, and one that surely matters to him too. But more than that, Scotty has lived a truly unique life. He has experienced almost everything in hockey, up close, for the best part of a century – and his is a life that no one else will live again. It’s a life that had to be captured.

Dryden on why he wrote the book – excerpt from Scotty, p. viii

Dryden applied a creative approach in developing the narrative of Bowman’s story. While most coaches love to tell colorful stories, this is not the case with his main subject. Bowman is different. “He is shy, and he is not a storyteller,” Dryden writes (Scotty, p. 14). “He’s a coach. He never stops being a coach. He’s too practical and focused, and storytelling is too fanciful.”

Therefore, Dryden gave Bowman an assignment. He asked him to pick the eight greatest teams in NHL history and to tell us why. Dryden would thereafter use the selected teams, chronologically, to weave in elements of Bowman’s own personal life and career story.

Then, in the latter part of the book, Bowman would create a bracket, playoff style, matching his selected teams against one another until an ultimate greatest team emerges. Dryden is, in fact, making Bowman a coach again, sharing his insight on players, strategies, tips on how he would coach with and against these players and lines combinations. Dryden creates an observation deck from which we can watch how someone with the expertise of 60 years in professional hockey analyses the game, taking into account the very different eras in which it was played.

The end result is a fascinating hockey history lesson given through the vision, interpretation and real-life experience of a legendary coach narrated by another hockey legend and famed writer. In the spirit of Dryden’s image as a thinker and compelling creator of colorful prose, the book is also an intellectual portrayal of the mind of the most successful coach in hockey and possibly all of sports. Dryden effectively intersects Bowman’s life story with some of the game’s key historical moments that will satisfy the most studious of hockey historians along with the coach’s thorough analysis of the best teams in the history of the NHL.

Bowman’s Top 8 Teams of All Time

- Detroit Red Wings, 1951-52

- Montreal Canadiens, 1955-56

- Toronto Maple Leafs, 1962-63

- Montreal Canadiens, 1976-77

- New York Islanders, 1981-82

- Edmonton Oilers, 1983-84

- Detroit Red Wings, 2001-02

- Chicago Blackhawks, 2014-15

The mix of teams selected by Bowman is eclectic in historical terms. Canadian and American teams, Original Six and post-expansion teams, before and after the introduction of the salary cap. Two of these teams he coached himself. In the process of writing and researching the book, Dryden took a hands-off approach in the selection. “I didn’t know which ones Scotty would pick, nor which matchups he would set,” Dryden writes (Scotty, p. 333). “I didn’t want anything to get in the way of the questions I would be asking him about each team.”

Out of respect for those who will want to read the book and follow Bowman’s thinking step-by-step, the results of the matchups will not be divulged here. Part of the pleasure of reading this book is learning about Bowman’s life through the performances of these teams and then, getting a chance to benefit from his deep knowledge of the game to fully understand his final selection.

As for Bowman’s colorful life and career path, we now explore some of the main highlights raised by Dryden.

Verdun and the Development of a Hockey Mind

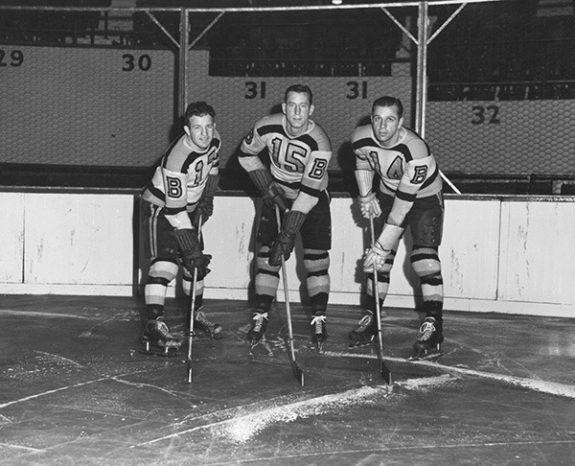

Bowman was born on Sept. 18, 1933, in Verdun, Quebec, a borough of Montreal situated along the St. Lawrence River. He grew up in an area called “the Avenues” where he was active in many sports and after-school activities such as Wolf Cubs and Boys Brigade. Hockey started to fill his imagination at the age of six when radio signals from Boston reached Verdun and he could hear the play-by-play of games being broadcast on the radio out of Boston Gardens. It was the 1939-40 season and, as a result, the Bruins became Bowman’s favorite team.

He was a good all-around athlete growing up. The young Bowman played baseball, soccer, and was a quarterback in football. In hockey, he was known as a good offensive player, a scorer. At the age of 14, playing midget on a Montreal Canadiens-sponsored team, he enjoyed the benefits of a great perk – a standing-room pass to the Montreal Forum where he could watch the Habs play anytime he wanted. He saw players such as Maurice Richard and Gordie Howe play live and become the legends they are today.

However, his dream of playing professional hockey ended in March 1952, when, playing for the Junior Canadiens, he suffered a fractured skull in a game played at the Forum. It was a life-changing event. He could no longer do all the activities he did before. While he recovered sufficiently to play hockey again, now with the Montreal Junior Royals, he was not the same player on the ice. “I was no longer a prospect,” Bowman laments (Scotty, p. 49). He painfully concluded that professional hockey was not a career option for him going forward.

Bowman was a decent student but it was not his calling. He refused a partial scholarship to attend Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in Troy, New York. The Canadiens also offered to pay his way through university but he decided instead to attend Sir George Williams College (now part of Concordia University). He also started to coach Canadiens-sponsored teams who played at Willibrord Park in Verdun. “This way he could do what he had always done, what he knew – go to school, and be involved in hockey – in the ways that were still open to him,” Dryden writes (Scotty, p. 63).

The Calls From Sam

Bowman finished his business studies and continued to coach bantam and juvenile teams in Verdun that were part of the extensive farm system set up by Frank Selke Sr., the legendary general manager of the Montreal Canadiens. He also started working for Sherwin-Williams, the big paint company that had a factory in Montreal at the foot of Atwater Hill and, most importantly, within close proximity to the Forum.

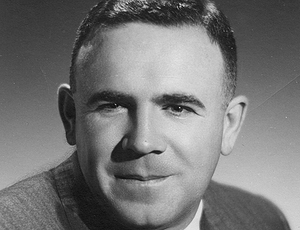

Strategically planning his lunch breaks from work, Bowman would watch practices run by head coach Dick Irving Sr. at the Forum. It was a unique opportunity to see up close how Maurice Richard practiced. “He didn’t joke around. He wanted to score goals. He wanted to score so much, even in practice,” Bowman remembers (Scotty, p. 72). His constant presence in the stands got him noticed, by the players, by Selke and also by Sam Pollock, an executive with the team and a person that was responsible for many of the activities and tasks required to operationalize Selke’s player succession plan. One day, he called Bowman.

Pollock gave Bowman his first full-time job in coaching when he asked the 22-year-old coach to become his assistant with the Junior A Canadiens. The team would begin playing in Ottawa. It was during this period that the tight relationship between the two really started to develop.

Later on, Pollock asked Bowman to coach the Peterborough Petes, a team that played in the Ontario Hockey League (OHL) and was also part of the Canadiens’ broad farm-team system. It was an opportunity to move out of an assistant’s role and be a head coach at a high level. It is also in Peterborough that Bowman learned a coaching approach that would serve him well later on in his career: “Know what you’ve got. Get your players to do what they can do. Find a way,” (Scotty, p. 121).

The environment in professional hockey is ever-changing. Soon, another opportunity within the broader Canadiens organization came up. At the request of Pollock, Bowman became the head scout of the Canadiens for Eastern Canada. While allowing Bowman to remain within the close orbit of the main team, it cemented his beliefs about his true calling. “During his years as a scout, Scotty learned two very big things. He learned that he didn’t want to be a scout. And he learned he wanted to be a coach,” Dryden explains of this period in Bowman’s rapid career development (Scotty, p.131).

When you’re a scout, even though you’re following the NHL and pulling for your team, you’re not involved. That’s the tough part of it. I had coached for five years, and when you’re not coaching it’s different. There’s a void. So I told Sam I wanted to coach.

Bowman on his stint as a scout for the Canadiens, excerpt from Scotty, p. 131.

The following season, 1963-64, Bowman became the coach of the Omaha Knights of the Central Professional Hockey League (CPHL). He was now coaching at the professional level. However, his first experience with coaching professional players did not last very long.

Dealing with Failure

Bowman quit his first professional coaching assignment after seven games. “He had arrived in Omaha at age 30, a wunderkind. He came back to Montreal not sure what he was,” Dryden explains (Scotty, p. 146). “Until this point, his downs had always been small ones, and his ups had been big ones, but this was failure.”

His own uncertainty increased and was compounded by the fact that Canadiens head coach Hector “Toe” Blake was not ready to leave. The situation created a lot of doubt in Bowman’s mind. What would he do next? Luckily, Pollock was there, again, to assist his protégé and assigned him as a scout in the Montreal area. He would also assist Pollock with whatever needed to be done.

By this time, Montreal was the site of a rich junior hockey scene. A fortuitous situation, a coach deciding to quit mid-season, allowed Bowman to get back behind the bench, this time for the NDG Monarchs of the Montreal Metropolitan Junior League. While the return to coaching in Montreal was a welcome outcome, it also came with another benefit. Bowman was now able to speak regularly and interact with Blake.

Off the ice, the Montreal Canadiens were also transitioning to a new era. Selke retired following the 1963-64 season, to be replaced by Pollock as the general manager. The NHL was in flux. Talk of a massive expansion was being heard more loudly.

Expansion Creates Opportunity

Expansion did occur. Starting with the 1967-68 season, six new teams were added to the NHL – the St. Louis Blues, Los Angeles Kings, California Seals, Minnesota North Stars, Pittsburgh Penguins and Philadelphia Flyers. These teams were grouped to form a western conference.

Lynn Patrick, son of hockey pioneer Lester Patrick, was hired as the first head coach of the St. Louis Blues. He gave Bowman his first opportunity in the NHL by adding him to the team as an assistant coach. After 16 games in the team’s inaugural season, Patrick stepped down as coach and named his young assistant to replace him. At the age of 34, Bowman was now a head coach in the NHL.

Success and Challenges in the NHL

Bowman led the Blues to the Stanley Cup finals in his first three seasons with the team. Essentially this meant that the Blues were the best of the expansion franchises, who all played in the same division, but still a big step behind the Original Six teams in terms of performance and skills. The Philadelphia Flyers would be the first expansion team to win the Cup and that would not be before 1973. Bowman remained with the Blues for four seasons and took on the role of general manager during his tenure. He left due to a contract dispute.

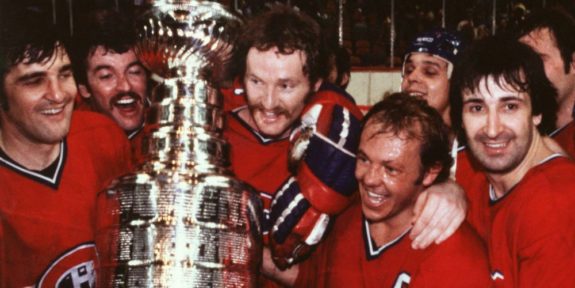

Changes were coming to the Canadiens after missing the playoffs during the 1969-70 season. It was another opportunity for Bowman who became the team’s head coach on June 9, 1971. The following day, Guy Lafleur was selected by the Canadiens as the first-overall pick of the draft, setting up part of the foundation of a team that would win five Stanley Cups in the eight years Bowman was behind the Canadiens’ bench.

Following the 1977-78 season and Bowman’s fourth Cup, his mentor Sam Pollock left the team. Expectations were high in Bowman’s mind that he would succeed him as the next general manager. When the position was given to Irving Grundman, the stage was set for an eventual exit but not before winning another Stanley Cup in 1979, Bowman’s fifth with the team and the Canadiens’ fourth in a row.

With a track record filled with successes, Bowman did not have to wait very long for his next assignment. The Buffalo Sabres offered Bowman the opportunity to also expand his portfolio by being both coach and general manager. The combined responsibilities were difficult to handle and it showed in Bowman’s and the team’s performance. It also reinforced, again, where his true connection to the game really was.

The toughest part when you’re doing both jobs is that when you’re not coaching you’re doing the phone calls, you’re doing the paperwork, and you’d rather be doing something else. When you’ve been a coach and you become a manager, you still have that coaching in you. Once you’ve coached and you’re not doing it anymore, the part of the game that is the most enjoyable is gone.

Bowman on having the dual role of head coach and general manager, excerpt from Scotty, p. 255.

Bowman was fired during the 1986-87 season. During his time with the Sabres, the team made five playoff appearances and missed the postseason once.

Interlude in the Broadcast Booth

Bowman was now 53 years old – not an easy age to redefine a brand new career path when your main expertise for so long has been leading professional hockey players. “He had been a player, a coach, a scout, and a manager, but throughout it all he had also been a hockey watcher,” Dryden writes (Scotty, p. 260). “That’s what he had been first as a kid, and what he had been all those years in St. Louis, Montreal, and Buffalo, and that’s what he still was and always would be.”

That ability served him well as an analyst on Hockey Night in Canada (HNIC). Now viewers from across Canada could benefit from his keen observations about the game, its players, and the strategies required to succeed. However, for Bowman, it did not give him the same satisfaction as coaching.

After doing the broadcasts for about a year, you start to get into a bit of a rut. It was nice coming to Montreal and watching the Canadiens play, but by the next year it all felt kind of empty because you’re not cheering for any particular team. You don’t care who wins or loses. The non-competitive part was hard. It wasn’t me. I didn’t like it.

Bowman on his time as an analyst for HNIC, excerpt from Scotty, p. 261.

In the summer of 1990, Bowman’s phone rang again. It was Craig Patrick, the general manager of the Pittsburgh Penguins. He had coached Patrick when he played for the Junior Canadiens. The Penguins were in the final stages of hiring Bob Johnson as their head coach and the team was looking to Bowman to be their director of player personnel. It was an arrangement that suited both Bowman and the needs of his family well.

He joined the Penguins in 1990. Following Johnson’s illness and eventual passing, Bowman was thrust again behind the bench of an NHL hockey team for the 1991-92 season. He led the team to a Stanley Cup, his sixth as a coach. Following the 1992-93 season, Bowman left Pittsburgh following a contract dispute.

Shortly after leaving the Penguins, Bowman got a call from his friend Jim Devellano from the Detroit Red Wings. Mike Ilitch, the owner of the team, wanted to talk to him about becoming the head coach. “It turned out to be the best move I ever made,” Bowman says of his move to Hockeytown (Scotty, p. 269).

Hockey was being transformed by globalization, a situation that would create a new challenge for Bowman and his coaching skills. Players beyond Canada and the United States were entering the NHL and creating new dynamics among players on the ice and within dressing rooms throughout the league. Bowman would need to adapt and merge different hockey styles on the same team from players who learned to play the game growing up in different countries such as Russia and Sweden.

Bowman’s time with the Red Wings would be his longest tenure with any of the NHL teams he coached, nine season, from 1993-94 to 2001-02 when he won his ninth and final Stanley Cup as a coach. He retired after that season.

Scotty Bowman: Hall of Fame Accomplishments

- Five Stanley Cup wins with the Montreal Canadiens as head coach (1973, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979)

- Two Stanley Cup wins with the Pittsburgh Penguins (as an executive in 1991, as head coach in 1992)

- Four Stanley Cup wins with the Detroit Red Wings (as head coach in 1997, 1998, 2002; as an executive in 2008)

- Two Jack Adams Awards (1977, Montreal Canadiens; 1996, Detroit Red Wings)

- Canada Cup Winner (1976)

- Inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame (1991)

- Three Stanley Cup wins as an executive with the Chicago Blackhawks (2010, 2013, 2015)

On Retirement

Echoing what he probably felt himself when he announced his own retirement, Dryden writes that “players and coaches think they retire when a season ends and they announce they are leaving. They don’t. They retire when the next training camp begins and they are not there,” (Scotty, p. 306). Bowman remained connected to hockey, still with the Red Wings at first, then with the Chicago Blackhawks. Retirement as a coach did not signify a separation from the game that had become synonymous with his life story.

In 2008, his son Stan, at the time the Blackhawks assistant general manager, was struggling with a recurrence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bowman’s fatherly responsibilities took over his hockey coaching instincts and compelled him to help the team as a senior advisor of hockey operations. His association with the team allowed him to experience more Stanley Cup victories in 2010, 2013 and 2015.

Final Thoughts

Dryden and Bowman receive a standing ovation following their talk in NDG. As I wait for an opportunity to get my copy of the book signed by the two legends, I reflect upon the stories and anecdotes that were shared that evening. The longevity of Bowman’s career in hockey intersecting with my own childhood memories of both him and his all-star goalie are still vivid in my mind even though they happened a long time ago. Just like the fans waiting outside prior to the event, we all have our hockey stories that have merged with the narratives of our own lives.

As I approach the table where the books are being signed, I recall a passage from Dryden’s acclaimed first book, The Game (first published by Macmillan Canada in 1983). Thinking about the many kids who would wait for their heroes at the players’ entrance of the Montreal Forum and noticing how they changed year after year, he writes: “In a life where games and seasons blend together, it is one of the few ways to know that time has passed,” (The Game, p. 28).

Handing Dryden my copy of the book to sign, I mention to him the passage from The Game I was thinking of and that I was surely one of the kids he was referring to when he wrote those lines. Looking up smiling, he says, “well, Steve, you have aged well.” We both laughed and as I left the amphitheater, thrilled to have interacted directly, ever so briefly, with two of hockey’s biggest names, I said to myself – “just like the amazing hockey stories in the book.”