Introducing The Hockey Writers’ Countdown to Puck Drop series. From now until the puck drops on the 2019-20 NHL’s regular season on Oct. 2 when the Toronto Maple Leafs host the Ottawa Senators, we’ll be producing content that’s connected to the number of days remaining on that particular day. Some posts may be associated with a player’s number, while others will be connected to a year or length of time. We’re really excited about this series as we take you through the remainder of summer in anticipation of the return of NHL hockey.

With 34 days remaining, we look back to one of the most dominant teams of the 20th century, the original Ottawa Senators. Existing from 1883 to 1934, the team was one of the founding members of the NHL in 1917 and is credited with 11 Stanley Cup victories, including a four-year unbeaten streak from 1903 to 1906 and another three from 1920 to 1923. If they were ranked among the modern NHL records, they would have the third-most Cup victories – the same as the Detroit Red Wings.

But in 1934, the Senators were finished. It wouldn’t be until 1992 that the city would see NHL hockey again, and though the two franchises share separate histories, the two teams will forever be connected. The Senators were instrumental in many developments, including the forming of the NHL, and so today, we look back at the rise and fall of the original Senators, hockey’s first dynasty.

The Early Years of Hockey

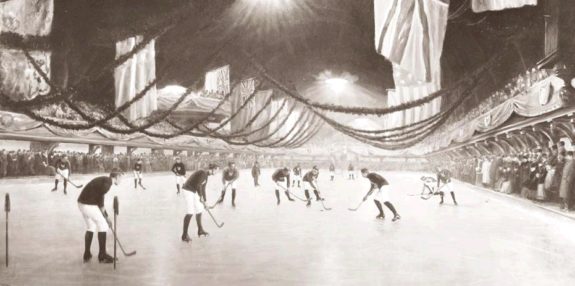

While versions of the sport had been played on frozen rivers and ponds almost 200 years, the first organized hockey game was only played in 1875 at the Victoria Rink in Montreal. It was organized by students at McGill University, prompting a few other rinks to host their own teams.

In an attempt to jump on to the growing popularity of the sport in the city, the Montreal Winter Carnival introduced its first hockey tournament in 1883, which consisted of three teams: the Victorias, McGill University, and the Quebec City Hockey Club.

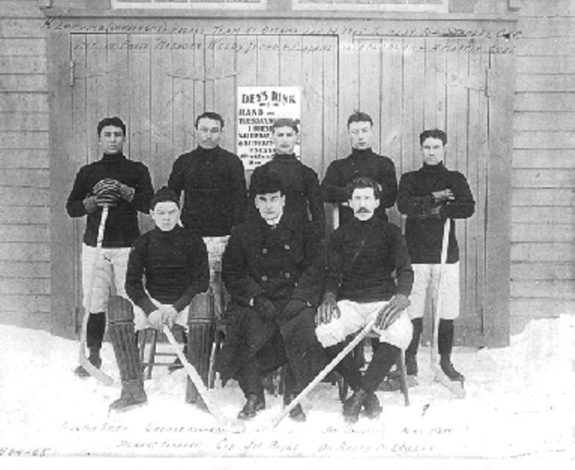

Among the crowd at the first hockey tournament were a group of hockey enthusiasts from Ottawa, who would get the idea to start their own team. They would call themselves simply the Ottawa Hockey Club (HC), and it would be the first organized hockey team in Ontario. They played their first game on Feb. 4 at the 1884 Winter Carnival, where they made the finals, but lost by a score of 1-0 to the Victorias.

Soon, teams were popping up all over Eastern Canada and it made sense to begin developing a hockey league. The Victorias invited both Quebec and Ottawa to join the teams in Montreal, but only Ottawa responded. So, with four teams in Montreal, and a lone representative from Ontario, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC) was formed in 1886. It operated very differently from the modern NHL, holding a challenge series each week from Jan. 1 until March 15, with each week’s winner taking home the championship.

Ottawa wasn’t satisfied, however. Despite the influx of teams from Quebec, Montreal and Halifax, they were still the only Ontario team, even though several clubs had formed since the formation of the AHAC. It prompted them to leave the AHAC in 1890 and form two new leagues: the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) and the Ottawa City Hockey League (OCHL). The OHA was one of the largest leagues at that time, consisting of 13 teams from Toronto, Ottawa, Kingston and Lindsay.

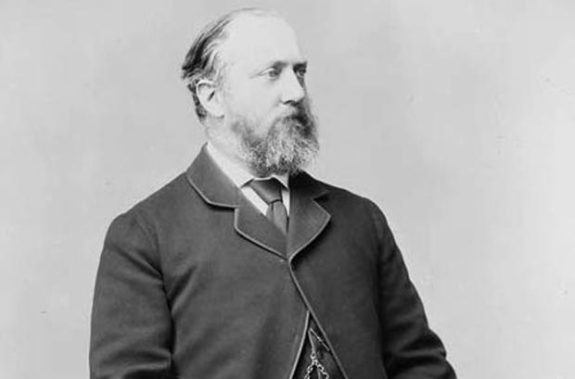

It seemed as though everyone had fallen for this new spectator sport, including the British-born Governor General of Canada, Lord Stanley of Preston. His two sons, Albert and Algernon, both played in the OCHL, allowing Lord Stanley to see many Ottawa HC games. Ottawa was clearly the best in the league, as well as the best in the OHA – they won both league championships in 1891 – but how did they compare with the AHAC teams?

A competition needed to be implemented, and with the help from his sons, Lord Stanley announced at an OHA meeting a new trophy for the 1892-93 season, which he titled the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup. The rules for winning ‘Stanley’s Cup’ were simple: any team could challenge the current holder for the prize, and the winner would either earn or retain the Cup. In order to accommodate the new challenge series, the AHAC changed it’s seasonal play to a round-robin style, on Lord Stanley’s suggestion.

At the end of the 1892-93 season, the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association won the most games (seven), one more than the second-place Ottawa HC, and were awarded the first Stanley Cup. Ottawa wasn’t pleased with this ruling, though. They had rejoined the AHAC in 1891, but remained in the OHA, where they were once again league champion, and believed they hadn’t been given an opportunity to challenge for the illustrious prize. So an adjustment was made to the rules, stating that the Cup could be won without a challenge if a team surpassed the current holder in the final league standings.

Lord Stanley would be called back to England in July 1893 to become the 16th Earl of Derby, and thus he would never see a challenge series for his Cup. But with the Stanley Cup now in the sights of every hockey team in Canada, a new era of hockey had dawned, and would soon be owned by one of the most formidable dynasties in pre-NHL hockey.

The Rise of the Silver Seven

Hockey continued to undergo many changes as the years progressed. Ottawa left the OHA in 1894, then left the AHAC in 1898 when another Ottawa-based team tried to join the league. The Ottawa Capitals had challenged the Victorias for the Cup in 1897 after winning their league, but were humiliated in the series 15-2. Many of the teams of the AHAC saw the Capitals as far weaker and undeserving of a place, but when they applied in 1898 after winning their league again, they were approved by a majority vote.

Rather than swallow their pride and accept the new team, Ottawa, Quebec, Montreal and the Victorias left the AHAC, effectively killing the league. The new league, titled the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL), shut out the Capitals and thus became the preeminent hockey league in Canada. Initially, the Montreal Shamrocks, who had joined the AHAC in 1895, were the top team in the CAHL, winning the Cup in the leagues’ first two years of operation. They were beaten in 1901 by the Winnipeg Victorias, who were beaten in 1902 by Montreal.

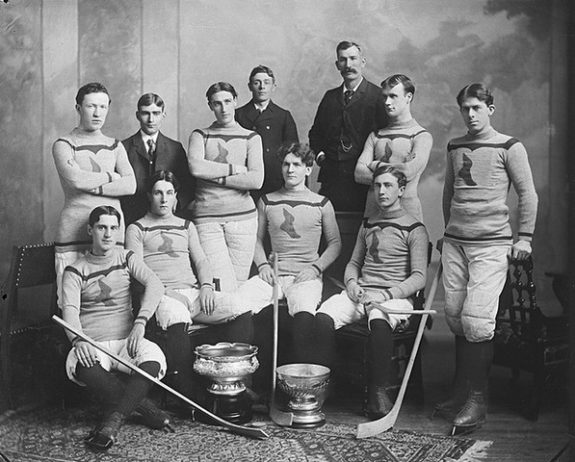

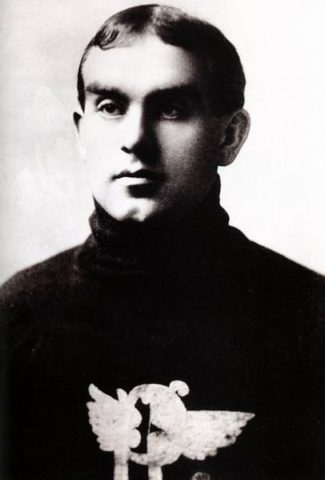

In 1903, after several players moved on to other teams, Frank McGee joined Ottawa. Just 21 years old, he had lost sight in his left eye during a hockey game in 1900, giving rise to the nickname ‘One-Eyed’. Yet what he lacked in vision, he made up for in pure skill. He quickly became the team’s star and one of the best players in the league, leading the team in goals with 14. With him, Ottawa claimed the CAHL championship in 1903, earning their first Stanley Cup.

Days after their victory, the Rat Portage Thistles challenged them for the Cup. Ottawa soundly repelled the challenger, outscoring the Thistles 10-4, with McGee scoring four goals alone. After the game, a local jeweler gave each of the seven Ottawa players a silver nugget, giving birth to the nickname the ‘Silver Seven’.

As the Silver Seven, Ottawa was practically unbeatable, and McGee got better every season. His most notable game came in 1905, when the Silver Seven were challenged by the Dawson City Nuggets, who traveled over five days and 4000-plus miles to Ottawa for the series, arriving just in time for the first game. They were talented, having several players on their roster who had formerly played for AHAC and CAHL teams, but tired after a long journey. However, Ottawa refused to change the date and beat the Nuggets 9-2.

McGee was uncharacteristically quiet, scoring only once in the game, causing one of the Nuggets’ players to remark that McGee wasn’t all that good. It struck a chord with the sniper and he erupted the following game, scoring 14 goals in a final score of 23-2. In the modern NHL, the highest single playoff game tally sits at five.

McGee would retire in 1906 after losing the Stanley Cup to the Montreal Wanderers, led by a young Lester Patrick, during the league finals. The two teams had tied in the standings, and after a two-game playoff, the Wanderers won by a two-goal differential. His career stats would sit at 134 goals in 45 matches, totals almost impossible to compare to modern players. With Ottawa, he would successfully defend the Cup ten times. McGee would go on to join the Canadian military and would be called up to fight in World War I, where he would die in the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Hockey Turns Professional

It was becoming apparent that the game of hockey had huge potential for profit. Teams had already begun charging for tickets and moving to larger arenas, and still, the fans kept coming. It prompted some leagues to abandon their strictly amateur status; the International Hockey League (IHL) based in Michigan had begun to pay all its players, which convinced some Canadian stars to turn professional and travel south.

In order to adapt to the changing landscape of the game, the CAHL merged with another amateur league to become the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association (ECAHA) in 1905. Although technically amateur, it allowed teams to hire professional players as long as the details were published. This change allowed the Kenora (formerly Rat Portage) Thistles to upset the Wanderers in 1907 for the Stanley Cup. The Thistles had employed professional Tommy Phillips, a star on par with the likes of McGee.

The Wanderers reclaimed the Cup just three months later, but Phillips had made himself a hot commodity in the ECAHA. He was offered a lucrative contract in 1907 from the Wanderers, but he decided to sign a cheaper deal with Ottawa instead, believing the Wanderers hadn’t delivered on all their promises. Still, Phillips became the highest-paid athlete in the country, making $1500 for a single season.

He joined two other high-profile professionals in Ottawa: Fred ‘Cyclone’ Taylor, one of the fastest players to ever lace a pair of skates, and Marty Walsh, who would go on to lead the league in scoring with 28 goals. Phillips would chip in 26 goals himself, while Taylor would be named the best cover-point (comparable to an offensive defenseman) in the league. Yet their efforts weren’t enough to surpass the Stanley Cup champion Wanderers, who went unbeaten in ten games to defend the trophy.

Phillips and Taylor left the following season, but Taylor returned in 1909 to Ottawa, who were now fully professional. The status change had caused some players to relocate to other leagues in order to retain their amateur title, leaving spaces for fresh talent. With the restructured roster, Walsh cruised to an incredible 38 goals, and the team scored 117 goals in total, 25 more than the second-place Wanderers. In the new professional era, Ottawa was untouchable, and they were Stanley Cup champions again in 1909.

There was only one problem. In 1910, the Wanderers came under new management who wanted to move the team to a smaller arena. Ottawa opposed the move, since it would result in smaller profits for visiting teams, but the new owners were undeterred. So, Ottawa convinced two other ECAHA members to leave the league and form the Canadian Hockey Association (CHA), which would no doubt be the more profitable league.

In response, the ECAHA renamed itself the National Hockey Association (NHA) and recruited some incredibly wealthy owners to support new teams. With the new money, Taylor was signed away from Ottawa for an unprecedented $5250, making him the highest-paid athlete in the world. They also added a new, purely francophone team in order to generate interest from the French-speaking public of Quebec, and called them Les Canadiens.

Ottawa, meanwhile, was struggling with the new CHA. Fans had remained loyal to the former ECAHA, resulting in low attendance and even lower profit margins. After seven weeks, Ottawa approached the NHA to see about a merger. The thriving NHA decided a full merger would hurt the league, so they instead accepted Ottawa and fellow defector, the Shamrocks. The loss of the two biggest teams caused the CHA to subsequently fold, leaving one league as the dominant source for hockey.

Forming the NHL

With the NHA, Ottawa decided to adopt a new nickname – the Senators. The moniker had been used unofficially for some time because of their location in Canada’s capital, but in the NHA, it finally became official. What didn’t change, however, was their rivalry with the Wanderers. The Wanderers topped the NHA in it’s first season, stealing away the Cup from the Senators, but the Senators claimed it back in 1911. Walsh put up one of his best seasons yet, scoring 35 goals in 16 games, on a team that outscored it’s opponents nearly two to one. In one challenge series, Walsh scored 10 times, nearly surpassing McGee’s record.

But once again, problems within the league began to emerge. In 1912-13, the NHA added two Toronto-based teams, nicknamed the Blueshirts and the Ontarios (later Shamrocks). Although they began under separate ownership, by 1915, they were owned by the same man – Eddie Livingstone. This did not sit well with the NHA, and even less so when Livingstone allowed the Shamrocks to go dormant, transferring several of the players to stock his depleted Blueshirts.

To even out the league, the NHA replaced the Shamrocks with the 228th Battalion, made up of players serving in the Canadian Army. They were the highest-scoring team in the league and beloved by the fans, but did not get along with Livingstone, as they were embroiled in a dispute over who owned star Duke Keats, further souring the owner to the NHA. It didn’t help his case when Livingstone accused Ottawa of tampering, claiming the owner had recruited Blueshirts’ star Cy Denneny during the summer, even helping him get a job in the city.

While the accusations were not unfounded, the fight lasted half the season, causing the NHA to tire of Toronto’s stubborn, cantankerous owner. When the 228th Battalion dropped out mid-season due to deployment overseas, the NHA decided to temporarily suspend the Blueshirts rather than have an odd number of teams. Livingstone responded poorly to the suspension, and when his team was reinstated at the end of the season, he launched into a series of ridiculous demands and lawsuits.

For the NHA, it was the final nail in his coffin. In a secret meeting in 1917, the rest of the teams decided to form a new league, one without Livingstone and his Blueshirts, which they called the National Hockey League (NHL). Although it started with five teams, the Quebec Bulldogs were forced to suspend operations before the season began, reducing the league to four. A temporary Toronto franchise was added to balance the schedule, but then Ottawa players began protesting their contracts, arguing they were only paid for 20 games, not the full 24. They were eventually placated, but not before they delayed their first game 15 minutes.

“Now that we got rid of Livingstone, we can get down to the business of making money.”

Ottawa owner Tommy Gorman after the formation of the NHL

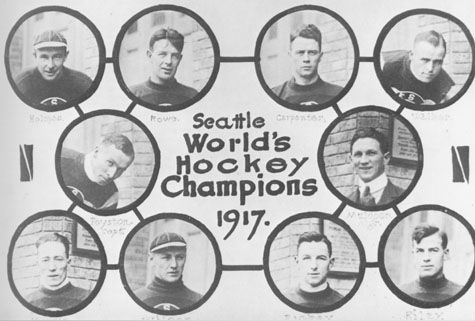

Then, midway through the season, the Wanderers’ arena burnt down, leaving them without a home and forced to also suspend operations. Too late to add another team, the NHL continued with three teams. Montreal’s Joe Malone would lead the league in scoring with 48 points, followed closely by Denneny’s 46, and Toronto would be the first league champion, although they’d lose the Stanley Cup to the Seattle Metropolitans.

Related: The Start of the NHL

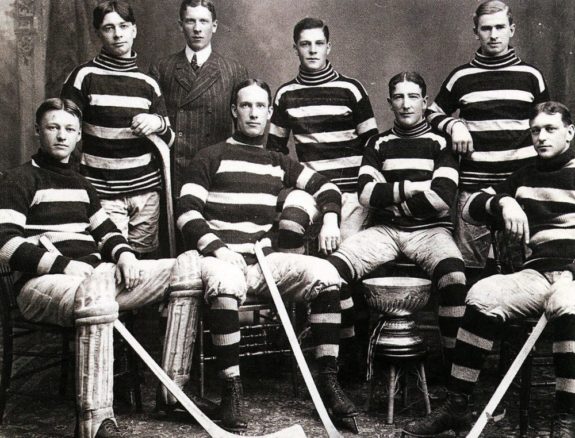

The Super Six Dynasty

In the early years of the NHL, there were two major differences from the modern game: first, the season was divided into two halves, and the winners of both halves would face each other for the championship; and second, the NHL champion would have to face the western champion for the Stanley Cup.

By 1920, the Senators had found their secret to success in goaltender Clint Benedict. He had put up an incredible season, putting up five shutouts and a 2.66 goals-against-average (GAA), despite the schedule adding four games to accommodate the reinstated Bulldogs. The next highest goaltender record was a 4.20 GAA with no shutouts. He led the Senators past the Western champions, the dominant Metropolitans, for the Senators first NHL Stanley Cup.

Although the Senators boasted offensive stars like Denneny, Frank Nighbor, and Punch Broadbent, their strength was Benedict, so they would leave both defensemen in their zone along with an extra forward. That strategy made them the toughest team to score on, and they successfully defended their Cup against the Vancouver Millionaires in 1921. They very nearly did so again in 1922, but lost to Toronto by a goal in the finals. In 1923, the Senators returned to the Cup Final against the Edmonton Eskimos, who they defeated 3-1.

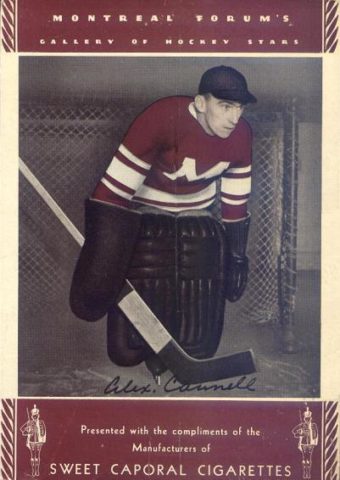

Finally, the NHL had enough of the Senators and president Frank Calder made a rule change for the 1925-26 season, dictating that no more than two defensemen could be in the defending team’s zone. But the Senators adapted, trading Broadbent and Benedict to the Montreal Maroons in 1924 and replacing them with Frank Finnigan and goalie Alex Connell. Nighbor became the first recipient of the Hart Trophy as the league’s most valuable player in 1924, as well as the Lady Byng Memorial Trophy in 1925, given to the most sportsmanlike player.

Related: NHL Dynasties: Which One is No. 1?

By 1927, all the western professional hockey leagues had disbanded, leaving the Stanley Cup solely to the NHL. However, now with ten teams, there was more than enough competition in the East, and it became the first season with divisional play. The Senators won the Canadian division, then defeated the Canadiens and Boston Bruins to claim their 11th Stanley Cup. Historians would dub these Senators the ‘Super Six’ as a call-back to the Silver Seven and in recognition of the NHL’s first dynasty.

The End of an Era

Despite their winning tendencies, the Senators began to lose money, largely due to their small market. After winning the Cup in 1927, the Senators had to seek financial relief from the league, as they had lost $50,000 on the season. In an effort to help generate income, the NHL allowed the Senators to play two “home” games in Detroit, where they would take the majority of ticket sales that night. For that reason, the Senators were able to turn a profit in 1927-28. It was also the season that saw Connell post a record 460-minute shutout streak, which still remains unbroken in 2019, yet the Senators would be upset by the Maroons in the first round of the playoffs

The following season, the Senators played two more games in Detroit, but were forced to sell players for cash to make ends meet. Denneny was sold to the Bruins, while Hooley Smith was sent to the Maroons. Predictably, the Senators missed the playoffs and continued to hemorrhage money. In 1929-30, the Senators played five home games abroad (two in Detroit, two in Atlantic City, and one in Boston). They made the playoffs, but were sent home early by the Rangers.

Related: NHL’s 10 Most Impressive Streaks

Nothing seemed to be able to keep money in Ottawa. By the time the 1930-31 season began, the Senators went on a selling spree which included sending Nighbor and Frank ‘King’ Clancy to Toronto, the latter for the incredible price tag of $35,000. Unsurprisingly, the Senators plummeted to last place for the first time since 1898. Then began the talk of relocation. First, an owner in Chicago offered to buy the team, but was blocked by the NHL’s Chicago Blackhawks who didn’t want another team in their territory.

Operations were suspended in 1930-31 due to financial problems, with some funds coming from loaning out players and other from the Bank of Montreal. There was also talk of moving to Toronto, as owner Conn Smythe wanted a second tenant in Maple Leaf Gardens. However, the Senators would have to pay Smythe a huge rent cheque, and so the deal was scrapped. The Senators returned for the 1931-32 season, but finished with the worst record in the league and often played to crowds of less than 4,000.

At the end of 1934, it was announced that the Senators would not return to Ottawa the following season. They were moved to St. Louis, where they became the Eagles, but the team was lacking talent after selling so many players, and the Eagles finished last in 1934-35. They suspended operations in the off-season and never returned to the NHL.

Professional hockey would elude Canada’s capital until 1972, when Ottawa would ice a team in the upstart World Hockey Association’s inaugural season, but would only last a single year. Then, in 1989, with the NHL reopening expansion talks, Ottawa launched the ‘Bring Back the Senators‘ campaign. The league would listen, and in 1990, the city was granted a franchise that would begin operations in 1992-93.

Although the modern Senators are not officially affiliated with the original team, the two histories are forever entwined. The 11 Stanley Cup championship teams are honored among the rafters of the Canadian Tire Center, and hopefully one day, the modern Senators will add their own Cup banner to hang with them.