The Edmonton Oilers and Detroit Red Wings made news recently by hiring new general managers, with Ken Holland joining the Oilers and Steve Yzerman returning to the Red Wings. Both teams have missed the playoffs the past few seasons, despite considerable talent on their roster, and so a change in management was deemed the best course of action.

It’s a common response by ownership to restructure the front office when a team fails to succeed after a long enough time. Generally, any change to a struggling franchise is seen as a step in the right direction. The results of such moves, however, are much more varied. Some teams see a change in direction almost immediately, while others take much, much longer.

History always seems to repeat itself, so I’ve gone and found two teams comparable to both the Red Wings and Oilers who eventually turned things around. Their stories offer some insight and guidance as to what the current struggles might lead to, and how to fix them.

Chicago Blackhawks

The Oilers’ hiring of Holland has been one of the most scrutinized moves during the 2018-19 offseason. The team has had four different GMs – including interim Keith Gretzky – since their last Cup Final appearance in 2007, yet nothing seems to have changed. Times are desperate in the NHL’s northernmost city, with patience wearing thin from management, fans, and players.

Still, the Oilers are nothing compared to the 1990s Chicago Blackhawks.

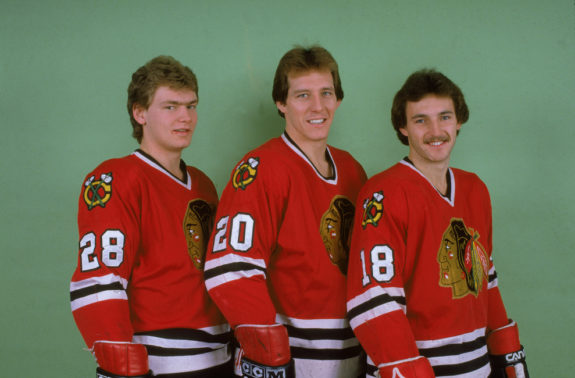

In 1988, the Blackhawks were frustrated. Despite several All-Stars and a future Hall-of-Famer, Chicago hadn’t been to the Final since 1972-73, and hadn’t won a Cup since 1961. Their current GM, Bob Pulford, had been behind the scenes since 1977, but with little else than some division titles. Thus a plan was put in place by the core leadership to transition Pulford into senior management and find a new GM to give the team a new vision.

Hiring Keenan as GM

That man would be Jack Adams winning coach Mike Keenan, who had just led his Philadelphia Flyers to the Stanley Cup Final. He joined the Blackhawks as their coach, replacing Bob Murdoch who coached just a single season, but Keenan knew that this was not the end goal.

On June 3, 1990, Keenan was named the Blackhawks’ fifth general manager, while retaining his coaching duties, and Pulford took on the new title of Senior VP of Hockey Operations. The move paid instant dividends as the Blackhawks won the Presidents’ Trophy in 1990-91, then made the Cup Final in 1991-92, only to fall to Mario Lemieux and the powerful Pittsburgh Penguins.

Keenan looked like the future of the franchise more so than any player, so owner Bill Wirtz offered Keenan the job of full-time GM in 1992, along with a five-year extension. Keenan had some reservations, as he’d always been a coach first, but he accepted, no doubt after seeing the strength of his team over his first four seasons. His first move, then, was to hire a new coach, and he chose former player and assistant coach, Darryl Sutter.

“I love to coach, and I have the ability to do a good job. It’s been a difficult transition for me to leave coaching this season, but I’m prepared to do what I have to do. I made the decision to hire Darryl, and, hopefully, it will work out.”

Mike Keenan on the change of direction (from ‘Keenan makes change in plans, decides future is with Chicago’, The Baltimore Sun – Oct 18, 1992)

However, everything backfired almost immediately. Not a month later, Keenan rejected the position, claiming he wanted to return to coaching, but also citing that a power struggle with Pulford and Wirtz left him as an insignificant player. Pulford returned as GM, rather than rush a new hiring that could hurt the team.

Suddenly, the Blackhawks had no plan, despite the years of planning and preparation. Pulford remained GM for five more seasons, but the team regressed, only appearing in the Conference Finals once. During that stretch, stars Jeremy Roenick and Ed Belfour were unhappily moved in cost-saving trades. By the time a new GM was hired, there were few stars left, and had sunk to near the bottom in the Western Conference.

Bob Murray was the new choice in Chicago; a former player and assistant GM with the team, he had the credentials, but it didn’t really matter. The Blackhawks missed the playoffs in 1997-98 and 1998-99, and Murray was fired midway into the 1999-00 season. Once again, Pulford returned as interim GM, while actively looking for a replacement who could offer what Keenan had nearly a decade earlier.

Related: 5 Worst Trades in Blackhawks History

Next came Mike Smith, hired in Sep. 2000, who had recently served as the general manager for the New York Rangers, but had previously been with the Blackhawks organization as a scout. With a team lacking any sort of momentum, Smith only lasted until midway through the 2002-03 season, when Pulford was forced to release him in order to keep coach Brian Sutter happy, leaving Pulford yet again as the team’s de facto GM.

By 2005, the storied Blackhawks were a mess. No matter who was in charge, the team seemed doomed to fail. Part of that was due to the people who were actually in charge – Pulford and Wirtz. Neither had shown the ability to adapt with the times, which angered former stars like Chris Chelios and isolated fans with cost-cutting moves. So, when Dale Tallon was hired as GM in 2005, there was little hope for any real change.

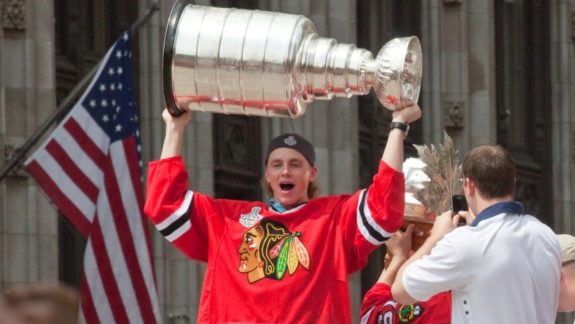

However, in 2007, the organization was shook. After a brief struggle with cancer, Wirtz died, transferring ownership to his son ,Rocky, who started his new job by making some sweeping changes. Suddenly, Chicago began to make drastic improvements, and were able to break their 49-year Cup drought in 2010.

“I loved my dad, and he was a wonderful businessman, but if you are not in front of big changes, you are going to be left in the dust.”

Rocky Wirtz, Chicago’s Comeback

Related: Irrelevance to Prominence: The Revival of the Blackhawks Franchise

Pittsburgh Penguins

When you think of modern-day hockey dynasties, two teams probably come to mind: the Red Wings and Penguins. The Red Wings dominated the early 2000s, winning four Cups in 11 years, while the Penguins have won three in the past eight. Yet there was a time that it looked like there wouldn’t be a Cup in Pittsburgh ever again.

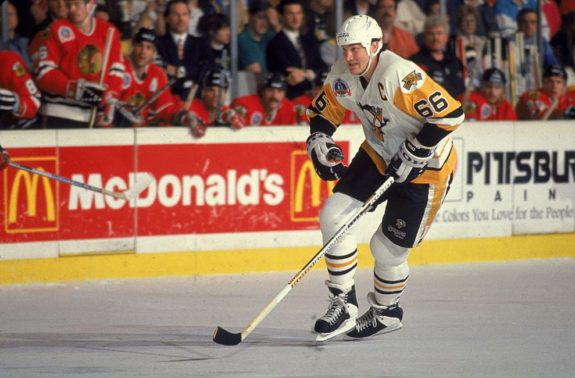

General manager Craig Patrick had built a monster in the early ’90s. Along with superstar Mario Lemieux, he also brought in Joe Mullen, Ron Francis, Ulf Samuelsson, Rick Tocchet, Larry Murphy, Paul Coffey and drafted a hot-shot Czech kid named Jaromir Jagr. That core captured back-to-back Stanley Cups in 1991 and 1992, and looked ready to keep winning for the next decade.

However, a roster full of stars also requires a lot of money, and at the time, the Penguins were one of the highest paid teams in the NHL. Jagr, Francis, Murphy and Tom Barrasso all had huge raises, ranging between $1 and $5 million, but none was bigger than Lemieux’s. In 1992, the superstar signed an eight-year, $42 million contract, one of the highest in the league, and would pay him over $11 million in 1996-97.

This was a major issue for owner Howard Baldwin, who was losing money left, right, and center. The massive deal to Lemieux, along with the huge raises, left Baldwin strapped for cash. Matters were made worse in 1994-95, after the lockout-shortened season sapped him of much of his revenue. Patrick was forced to strip down the roster in order for the team to be able to pay its players, which it still couldn’t do.

Then, the biggest bomb to the franchise dropped in 1997, when Lemieux announced his retirement due to cancer treatment. It was the final nail in the coffin. Attendance dropped, and in 1998, the Penguins declared bankruptcy. Baldwin had already been asking players to defer their salaries, with Lemieux still being owed more than $30 million a year after retirement, and there was still an arena deal to finalize.

Super Mario Saves the Team

Thankfully, Lemieux offered to purchase the Penguins and transfer his deferred salary into equity. But there was still the issue of paying off debts, and Patrick was forced to strip the roster even more: Francis left via free agency in 1998, Barrasso was traded to the Ottawa Senators in 2000, and Jagr was traded to the Washington Capitals during the 2001 offseason, all for practically nothing. Pittsburgh had officially been gutted.

Expectedly, the Penguins plummeted in the standings, missing the playoffs the next four seasons. Not all hope was lost, however, as Patrick was able to grab top prospects in the draft like Marc-Andre Fleury, Evgeni Malkin, and Sidney Crosby, but still relied heavily on veterans. In 2006, the time had come for the Penguins’ long-time GM. Patrick was let go after the 2005-06 season.

Ray Shero took over after Patrick. A former assistant GM with the Senators and Nashville Predators, Pittsburgh would be his first time as the GM. He inherited a great team, which Patrick had a large part in constructing, but also the financial issues. Problems getting a new arena deal was forcing the team ever closer to relocation, and more financial constraints were causing the problem to stretch deep into the season.

With Crosby becoming the new face of the NHL, however, both sides realized Pittsburgh would be profitable…eventually. With a fresh perspective, Shero knew the team just needed some time. He couldn’t have been more right. In 2009, Crosby, Malkin and Fleury helped the Penguins win their first Cup since 1992 and become one of the most dominant teams of the 2010s.

Back to Edmonton and Detroit

So, how do these tales relate to the new GMs in Detroit and Edmonton?

Like the early 2000s Penguins, the Red Wings have been struggling due to the retirements of Henrik Zetterberg and Pavel Datsyuk, sinking lower and lower in the standings. Like Patrick, Holland has received criticism for giving too many expensive, long-term deals to middling players. But a strong core exists, albeit not as talented as the one in Pittsburgh, and the best strategy may be patience.

Edmonton is a bit more complicated. Like the Blackhawks, their owner has been criticized for being a bit too involved in hockey operations, such as insisting Nail Yakupov was taken instead of Ryan Murray in 2012. But there’s little that can be done about that. The hiring of Holland does seem to be a step away from the ‘old boy’s club’ stereotype, but only time will tell if the Oilers can stop getting in their own way.