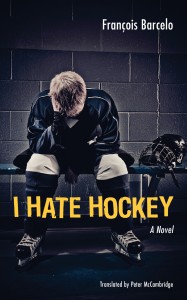

Governor General Award-winning author Francois Barcelo and translator Peter McCambridge have combined to produce a brisk and often disturbing piece of fiction in I Hate Hockey. At fewer than 100 pages, Barcelo’s fortieth novel, and his first available in English, is the literary equivalent of a sudden-death shootout – tense, unpredictable, and over before you know it.

Ostensibly, the story unfolds as a standard whodunnit, with a dead hockey coach at the center of an increasingly sinister set of circumstances. Readers are kept guessing until the end, but Barcelo plays fair and none will feel cheated when the final secrets are revealed.

When the story opens, the death that drives the plot has already occurred. Readers meet Antoine Vachon, divorced father, unemployed car salesman, and self-professed hockey-hater, who is cajoled into replacing the recently deceased bench-boss. After all, it is his son’s team.

From there, the reader is sped through a series of events that include an on-ice brawl, a 230 kilometer bus ride, allegations of sexual abuse, misguided escapes, and discoveries of grisly murder details, before the plot climaxes in dramatic fashion.

But while there is plenty going around Vachon, no where is the story more active than inside his head. The reader is treated to the protagonist’s quirky and politically incorrect musings on a bizarre topics, ranging from the type of people who drive Saturns, to how his town became “Quebec’s Capital of Exotic Cooking”. On occasion these soliloquies go on for too long, but they do not take away from the story’s momentum.

Even the writing style employed by Barcelo keeps the action centered on Vachon by limiting dialogue and using dashes in lieu of quotations to indicate Vachon’s verbal interactions.

Other reviews have noted that Vachon is unlikely to be adored by readers. His views on immigrants, women, gays, and the world at large prevent anything like adoration. Vachon’s self-centeredness and refusal to take responsibility for his actions are thematic, and crucial to the plot.

“I don’t think [Vachon] learns very much over the course of the novel at all. Which is, of course, the source of the tragedy. And the comedy.” Peter McCambridge, translator of Francois Barcelo’s I Hate Hockey

But the bumbling Vachon’s self-deprecating humor makes him winsome in moments, and it’s hard to hate someone so completely inept. As described by McCambridge, who read the book multiple times while translating the work, “I don’t think [Vachon] learns very much over the course of the novel at all. Which is, of course, the source of the tragedy. And the comedy.”

Readers will recognize classic Shakespearean comedic devices such as disguised genders, mix-ups, and relationship coincidences borrowed directly from works such as Twelfth Night. And only the most puritan of readers won’t crack a smile at some of the Vachon’s more outrageous observations. The book is genuinely funny.

But the book is also disturbing.

Not because of the horrific acts it contains (although these are significant enough to have attracted some criticism), but instead because of Vachon’s reactions in the face of such horror.

At one point, Vachon admits that he’s “no good at dealing with other people’s feelings anyways. I can’t remember holding Johnathan against me since he was, I don’t know, seven or eight. Or six.”

When confronted with the likelihood that his teenage son has been sexually abused, Vachon’s first reaction isn’t rage or sorrow, but instead he concludes that “no wonder he’s playing centre for the best left-winger on the team”, and it isn’t long before Vachon is back thinking about himself, pondering his chances at remaining on as head coach.

Or consider how Vachon works through the possibility that his teenage son may have committed murder. “As I walk back to the motel, I try to imagine Johnathan hitting a man over the head with a baseball bat. I can’t do it, because I don’t know where the murder took place. And it’s hard to imagine something when you don’t have a clue what the crime scene looked like.”

These statements betray something underdeveloped, or missing altogether, in the Vachon character. His detached reactions go beyond an inability deal with others’ feelings – his inner dialogue suggests that Vachon is devoid of an emotional response.

In this regard Barcelo pays tribute to Albert Camus’ The Stranger. In that famous work, the titular character Meursault fails to understand why others see emotional significance in the death of his mother, his girlfriend’s love, or even when he takes the life of another man. By the end, Meursault is deemed inhuman, a dangerous stranger unrecognizable to the rest of us, and is executed as an unrepentant murderer.

Vachon’s responses, though almost always humorous, display this same lack of emotional awareness.

Ultimately, despite its weightier elements, I Hate Hockey remains a fast-paced and entertaining read that delivers a satisfying conclusion that will keep readers thinking even after the final page is turned.

It’s attention-grabbing title notwithstanding, Barcelo’s story isn’t about hockey, but he uses it as a bridge to lead us into a dark world; one populated with heinous acts and monsters, some of whom are hiding in plain sight. But at least he gives fair warning – I mean really, what kind of person hates hockey?

More info can be found at the I Hate Hockey Facebook page, or the Baraka Books website.

Thanks for such an insightful review, Brent. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. I particularly liked your comparison to Meursault. It made me think of a line from Camus’ novel, something along the lines of Meursault “refusing to play the game.” Most people know Camus was a big soccer fan, but I can only assume he meant hockey here.

I would also add that I think Antoine’s isolation from society is largely caused by his divorce from hockey. Hockey is the one thing that brings all Canadians together and instead Antoine finds himself distanced from his wife, his won, his boss, everyone around him…

But as you say, what kind of person doesn’t like hockey anyway?