PHILADELPHIA — Dan Craig sleeps maybe four hours a night leading up to outdoor games. He only goes out to dinner because he can check the status of the ice on his phone.

“Your mind’s always going,” said Craig, the NHL’s vice-president of facilities operations.

After staging outdoor games in a deep freeze (Edmonton) and summerlike warmth (Los Angeles), the NHL seems capable of taking hockey outside just about anywhere in the U.S. and Canada knowing the ice will be almost as good as the sheets found inside.

When the Flyers host the Penguins on Saturday night, it will be the 27th NHL outdoor game since 2003. Next season’s Winter Classic is at the Cotton Bowl in Dallas, where the average high on Jan. 1 is 56 degrees (13.3 Celsius).

No worries, hockey fans.

“We put the parameters out there as into what we feel the challenges are going to be at a certain climate in a certain area and this is what we’re going to run up against,” said Craig, who has worked all but two outdoor games. “And if we have to go to get different equipment, we go get different equipment. If we need more staff, we just go get more qualified people to come in and give us a hand to make sure that everything works the way it’s supposed to.”

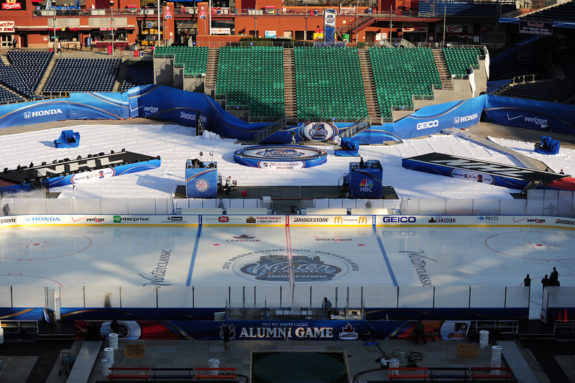

Weather is the biggest hurdle that can’t be controlled. It is instead managed by Craig, his son Mike, senior facilities operations manager Derek King and the 100-person crews that work each game. As he sat on the boards Thursday at Lincoln Financial Field, Craig pointed to the sky and acknowledged the swirling wind was on his mind.

Still, improved technology and techniques learned over the past 15 years have helped perfect the science and execution of making and maintaining outdoor ice.

It starts with a 53-foot refrigeration truck that feeds coolant into aluminum trays set up on the field, and while indoor facilities have ice typically an inch or so deep, outdoor rinks go beyond 2 inches to protect the surface from the elements. Smaller Zambonis have less impact on the ice, and covering the surface with heat-reflecting insulation tarps helps. The ice can be monitored with sensors that provide real-time readings to a smartphone app.

The ideal ice temperature is 22 degrees (-5.5 Celsius), but all was fine in Denver in 2016 when it was 65 (18.3 Celsius) because officials can just turn the A/C up.

“When we’re monitoring the air temperature we’ll just make the sheet colder,” King said. “If we can keep it in the in the mid-40s, it would be great. But we’ve got a lot of control. … We have a lot of control of the truck, so we can manipulate our temperatures on the sheet with the air temperature.”

Craig remembers the 2014 Winter Classic at Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor: The snow shovelling started at 5 a.m. and never really stopped. The sun has been just as big an impediment — it delayed the 2012 Winter Classic in Philadelphia because the glare was considered a danger to players. The ice at the 2011 Heritage Classic in Calgary had to be covered because it was so cold there were worries the surface would crack, the most concerned Craig has ever been.

The tarps with air bubbles inside became a mainstay beginning in 2014 at Dodger Stadium to combat the Southern California sun as temperatures soared to almost 80 (26.7 Celsius) in the days before the game.

“Sun was a huge issue for us in just the temperature on the ice, so we kind of came up with a system of how to cover the ice and reflect that sun,” King said. “We still use those same ideas anywhere we go.”

The Dodger Stadium experience showed the NHL’s ice crew it could adapt to just about any situation. Previous weather dilemmas also taught Craig and his staff they couldn’t just leave snow on the ice like so many nature-made rinks in cold climates, which paid dividends this week in Philadelphia when snow turned to sleet and then rain.

“Everybody’s looking at us like, ‘Why don’t you just leave the snow?’ Well, it’s going to cause us 18 hours of work if we don’t get the snow off, like, right now,” Craig said. “(If) it happened to rain, the top is going to freeze and then the bottom is going to be nice and soft. Well, no. Where we were, it just goes all the way through and then it freezes to the bottom. Those are the types of things that we have learned over time: how to manage the different circumstances that were put into.”

There are three more outdoor games next season — in Regina, Saskatchewan, Dallas and the Air Force Academy in Colorado — and trips to Nashville and maybe even Las Vegas could be coming someday.

Craig doesn’t see any challenge as too daunting and he is focused on giving players an unforgettable experience.

“They step out there for the first time and they do about three laps around and the grins and their eyes are just phenomenal,” he said. “They’ve always been in organized hockey, they’ve always been indoors, they’ve always travelled and all of a sudden they get their chance. That’s when you see the guys and you just see them, they’re beaming because this the first time, they’re getting paid for it, they’re playing a game that they love and they’re playing it outdoors where we started.”

___

More AP NHL: https://apnews.com/NHL and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

___

Follow AP Hockey Writer Stephen Whyno on Twitter at https://twitter.com/SWhyno

Stephen Whyno, The Associated Press