by Jas Faulkner, senior correspondent

author’s note: Stick taps to Andrea Lindgren and Phyl Good for catching that Ryan Kesler is actually American by birth (a Canuck by the grace of the Hockey Gods.) ::sigh:: It had to be the naked one…

Sidney Crosby’s return to the ice is a cause for celebration for not only his immediate circle of friends and family and the Pittsburgh sports community, but for everyone involved with hockey. His recovery provided the league with hope that the right kind of care can mitigate what could have been a career-ending injury.

Crosby’s comeback raises some interesting questions about the nature of stardom in the NHL. What does and doesn’t pass muster when public images are made and marquee names are ingrained into the popular imagination? Before the concussion that put him on IR, Crosby was considered the face of the NHL by some and a spoiled infant terrible who was given a pass for behaviour unbecoming of a sports hero by others. By the numbers, it is beyond argument that Crosby is that good on the ice. As a talking head and pitchman, he is by all appearances reticent, almost reluctant, compared to many members of the NHL, including his arch-rival, Alexander Ovechkin. With so many personable, talented players who are more willing to step into the spotlight, what is it about Crosby that elicits such intense emotion?

They Might Have Been Kings

In the months following Crosby’s concussion, the Broadcast Powers That Be needed something to offer viewers to replace the Alex ‘n Sidney Show. Since they were no longer relegated to being spear carriers and supporting players in the Ovechkin-Crosby saga, a hand full of athletes began to catch the attention of the viewing public. Anaheim’s Cory Perry and the Canucks’ Ryan Kesler are Western Conference hot shots, marquee names in their own cities who became familiar faces to more casual fans. Both are big, good looking young men who emerged from the same “Leave it to Beaver” suburban bliss as Crosby. Their drama-free leadership on and off the ice and their teams’ playoff runs gave them more media exposure than they (or their counterparts in earlier seasons) might have received. Young, talented players such as Edmonton’s Jordan Eberle, Taylor Hall and Devan Dubnyk showed what they could do and garnered new respect for the often

underrated Alberta franchise. In Raleigh, Jeff Skinner continued to generate interest in the fortunes of the Hurricanes. A little further south, Tampa Bay’s Steven Stamkos and Martin St Louis reminded North America and beyond that Florida had more to offer than sandy beaches and pastel architecture.

Meanwhile, the other half of the starcrossed rivalry that fueled the imagination of the league for three years was, if not languishing, at the very least having a year that was relatively speaking, less than remarkable. By all rights this should have been Alexander Ovechkin’s time to shine. Often cast as the less cuddly half of the NHL’s most heated personal rivalry, the player who launched a thousand arguments between “Team Alex” and “Team Sidney” spent too much time sidelined by injuries and disciplinary sanctions to pay much attention to the fight for the limelight.

The Big Picture – Historically Speaking

The roots of the NHL are found in men who painted houses, worked in factories, and sold insurance in the off-season so they could afford to spend the winter months on the ice. The cloistered environment and developmental pre-NHL incubation period that can sometimes stretch into half a decade for today’s players would have been completely unthinkable to the league’s first major star, Newsy Lalonde.

Born Edourde Cyrille Lalonde on Halloween in 1887, he was the first “Flying Frenchman” to wear a Habitants sweater and the first to put a puck in the net for the Canadiens. Like many players from the early Twentieth Century, Lalonde’s nickname was a reflection of the life he led off the ice and before his years as a household name. Lalonde was a runner and line worker in a newspaper plant as a very young man, which led to his nickname, “Newsy”. Lalonde’s moniker belied the professional success he experienced as a member of Canada’s newest and fastest rising team, the Montreal Canadiens, and his place in the Canadian media’s popular firmament as the country’s leading lacrosse player. In spite of the glaring differences in their entrances into the league, Sidney Crosby has far more in common with Newsy Lalonde than some of his more contemporary counterparts.

Like Crosby, Lalonde was an exceptional, almost otherworldly talent when he was on the ice. He was identifiable to the Canadian public as the face of the game in a way that went beyond the ken of hockey’s loyal fan base. Just like Sid the Kid, Newsy was apt at exciting both adoration from his fans for his skill as a player and ire from followers of the opposing teams due to the perception (warranted or not) that his sins were being overlooked. Reporters and fans characterised his play as “stick-happy”. Failure on the part of the officials to come down hard on Lalonde for his errant swings led some to believe that his premature lionisation as a legend precluded any objective evaluation of his value as a player.

Je Ne Sais Quoi and a Dangerous Presence on the Ice

Few accusations of the sort would be leveled against the next big name in the game. Howie Morenz’ rise through the ranks of midgets to

minors to the NHL was marked by long years of hard work. Like many stars to follow over the century, he was an “overnight sensation”

ten (or more) years in the making. Morenz and everyone so annointed as a “Great One” would represent some variation of the big shouldered, hard working team leader who toed the line where the code was concerned but never failed to place a high value on winning.

With so many truly great players, it is sometimes easy to dismiss those whose names gain currency in the general popular canon. The nature of their fame causes a separation from the very thing that gave them their notoriety in the first place. We ask, “Why him? Why Gretzky? Why Orr or Howe or Richard or Lemieux? What is it about these men that make them stand out among so many others?” There is the phenomenal degree of talent. There are the iconic moments that are dissected and become components in the vocational toolboxes of the next generation of players. In some cases, the private lives of these men sometimes eclipse their accomplishments in the rink. This can make what happens between the initial puck drop and the final buzzer feel beside the point.

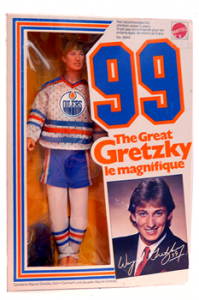

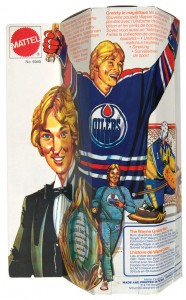

Wayne Gretzky may be the most extreme example of this process. Before everyone figured out that

most of the best television comedy in the US was written by Canadian ex-pats and the AOR radio public was assailed by the post-Francophone warbling of Celine Dion*, the best known Canadian export was a young centre who set Edmonton and the hockey-loving public on fire. Gretzky’s move to Los Angeles in 1988 was shocking to many. Among his fellow countrymen, there were rumblings that he was a traitor to his Canadian roots. As he began to find recognition beyond the sport as a public persona, it was easy to dismiss him as having “gone Hollywood”. The Gretzky doll, produced by the same division of Mattel responsible for Barbie and Ken and the appearances in television and in movies (including a brief stint on a US soaper, “The Young and the Restless”) did little to convince skeptics that there was more to Gretzky than the hype. To the hardliners who were devoted to Gretzky the hockey player, it was tantamount to losing someone who had been important to a very specific community to the larger general population. Wayne Gretzky no longer belonged just to hockey fans and in a way, was no longer one of the borderless nation who stood at both sides of the glass, united by a love of the game above all else.

Wayne Gretzky, Mario Lemieux and Steve Yzerman all die and meet in heaven…

God is sitting in his chair waiting for them. God says to the three legends, gentlemen before I let you in, you must tell me what you believe. “Mario we’ll start with you, in what do you believe?” “I believe hockey is the greatest thing in the world and the best sport in history”. To that God says “take the seat to my left”. God then turns to Steve and says, “Steve, in what do you believe?” To which Steve replies “I believe to be the best, you’ve got to give every ounce you’ve got!” To that God says “take the seat to my right”. God then turns to number 99 and says “Wayne, tell me what do you believe?” To which Wayne replies “I believe you are sitting in my seat.” -via Anonymous Internet Sports Joke Sites

Knowledgeable hockey fans may not be fond of the public personas. They may eventually come to scorn players they loved in an earlier time, but they never lose the excitement they felt the first time they saw how amazing they were/are on the ice. That someone as young as Sidney Crosby is experiencing this so soon in what looks to be a long career in the NHL says more about the nature of star-making within the NHL and celebrity in general than it does about the object of that attention. While Crosby (and to a slightly

lesser extent, Ovechkin) may have interests outside of the game, it’s what happens from the time their blades

touch the ice to the time they walk down the ramp that seems to motivate them the most.

Quicker roster turnovers and shorter professional lifespans necessitate some of the money-making activities that give the superficial appearance of having been seduced by the trappings of fame and wealth for its own sake. This is where today’s latest leading men have much more in common with the starring players of a century ago than they do with those who graced the covers of The Sporting News fifty, twenty-five, even ten years ago. The thing to keep in mind is that, at least for Sid and Sasha, doing what it takes to keep the revenues high and leaving the numbers to the suits so they can concentrate on the game is nothing more than smart business that will keep the machine running so theycan do what they do best, which is play hockey.

*So shoot me. I like her earlier French recordings.