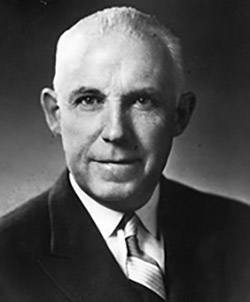

The father of the NHL draft would probably have trouble comprehending his creation today.

When then-league president Clarence Campbell instituted the draft, first held 59 years ago, it was a simple and not particularly relevant affair in which the best young hockey talent didn’t participate due to an archaic, unbalanced system which allowed teams to lock up future stars early. Yet the draft’s form and relevance in 2022 would be sure to both shock and evoke admiration in Campbell, who introduced it as a means of doing away with the old ways, giving birth to what became a layered, complex and comprehensive mechanism of distributing the sport’s youthful prodigies equitably throughout the league.

Perhaps Campbell, who died in 1984, would be more wowed by an NHL made up of 32 teams, rather than the Original Six era over which he partially presided during his 31-year tenure. Yet it’s undeniable that Campbell, who was instrumental in the league’s expansion, would be amazed by what began as such a modest endeavor in 1963.

Today’s draft utilizes a lottery system that’s gone through several incarnations, all of them focused on the enduring idea of forging the fairest method of access to the top young players. The driving force behind that is the ongoing battle to disincentivize “tanking” in order to guarantee a shot at a generational talent, which the NHL identified as a threat to the integrity of its product nearly 30 years ago and began to adjust accordingly.

Modern NHL Draft Had Very Humble Beginnings

As foreign as today’s draft process would seem to Campbell, a look back at the 1963 draft is equally disorienting for the present-day fan: Four rounds, 21 total selections, most of them no-names – and all of them Canadian. The only ones of note? Second overall pick Peter Mahovlich, who recorded 773 points in 884 games and is the brother of Hockey Hall of Famer Frank Mahovlich; and defenseman Jim McKenny, who enjoyed a 604-game NHL career and was the only player in that draft besides Peter Mahovlich to earn All-Star honors. Five of the original 21 picks made it to the NHL.

It’s been quite the journey from those days to the seven-round, 225-player, two-day fully televised event of 2022 that’s scheduled to take place July 7-8 at Montreal’s Bell Centre. For instance, the draft order 59 years ago was determined by giving teams the choice of where they would select, starting with the club that had the worst record the season prior. In the ensuing drafts, the teams would then move up one spot in the order – regardless of season record.

The cellar-dwelling Boston Bruins, for some reason, chose to pick third instead of first. The Detroit Red Wings opted not to make their third- and fourth-round choices, and the Chicago Black Hawks (then spelled out as two words) elected not to draft a player with their fourth-round selection.

Yet as alien as all of that must seem today, the first draft marked the beginning of tearing down the inequitable process of player procurement that was in place. Campbell’s genius was in his correct assessment that the system was a dinosaur that had to go for the NHL to grow into the type of mass-appeal league that it is now – one in which a handful of powerful teams couldn’t hoard future stars and thus, largely prohibit long-term success for all but those select few.

Prior to the inception of the draft, the very best prospects were spoken for early. NHL teams did that by sponsoring amateur teams and players, which through contracts tied those players to the team sponsoring their amateur clubs, thus giving NHL organizations total control over their pro future. For example, Hall of Fame defenseman Bobby Orr, who would have almost certainly been the first pick in the draft, signed with the Boston Bruins in 1962 at age 14 after they had paid $1,000 in Canadian dollars to sponsor Orr’s minor team the year before. Fellow Hall of Famer Phil Esposito, with whom Orr teamed to make the Bruins into a 1970s powerhouse, was signed as a teenager by the Black Hawks and played four seasons with them before being traded to Boston in 1967.

Campbell instituted the draft precisely for the next phase of transformation that began July 1, 1967, with the direct sponsorship of lower-level teams by NHL clubs to be phased out going forward, and sponsored players being prohibited from signing deals that tied them to NHL teams. The first draft conducted after the full elimination of that system occurred in 1969 – which came two seasons after the league had doubled in size to 12 teams, making the new rules timely in leveling the talent procurement playing field for the new clubs – and was perhaps the first that bore some resemblance to the drafts of today.

Six future All-Stars emerged from those selections, including Hall of Famer Bobby Clarke of the Philadelphia Flyers in the second round. There was also Butch Goring, a cornerstone of the New York Islanders’ early-1980s dynasty who was chosen in the fifth round by the Los Angeles Kings, and standout center Ivan Boldirev, who recorded 866 points in 1,053 career games. That draft included five non-Canadian players, more than all of the previous drafts combined.

Draft Started to Undergo Major Changes as NHL Grew

The draft’s evolution continued. The rules were changed again in 1979 to allow players who had previously played professionally to be drafted, and a new name came along with that – the NHL Amateur Draft taking on its current moniker, the NHL Entry Draft. Starting in 1980, any player between the age of 18 and 20 became eligible to be drafted, with any non-North American player over the age of 20 also able to be chosen.

Yet another major shift occurred that year, with the draft becoming a public event, taking place at the Montreal Forum after previously being held in Montreal hotels or league offices in private. Four years later, the draft was televised live for the first time, by the CBC in English and French, and in 1987 was held in the United States for the first time, at Detroit’s Joe Louis Arena.

Speaking of Montreal: Though it hardly benefited the Canadiens (contrary to popular myth), the team that built a dynasty that stretched from the late 1960s through the late 70s briefly enjoyed an agreement with the league that allowed them to draft two French-Canadian players before any other team, an arrangement in place for the first seven NHL drafts. The Habs didn’t add any significant pieces to their storied ranks through the clause, though; in fact, they didn’t even use it for the first five years. That’s because most top-tier prospects were still unavailable due to the sponsorship pacts.

Montreal’s real advantage, of course, flowed from the system that Campbell had worked to eliminate. With extensive sponsorship agreements, the Canadiens had built a feeder program which they used to control most of the elite prospects in their talent-rich home province of Quebec – and in other parts of North America as well. The seven-year French-Canadian agreement with the NHL was a compensatory move for the Habs losing that vast infrastructure, though it ended up having little to no impact on their roster.

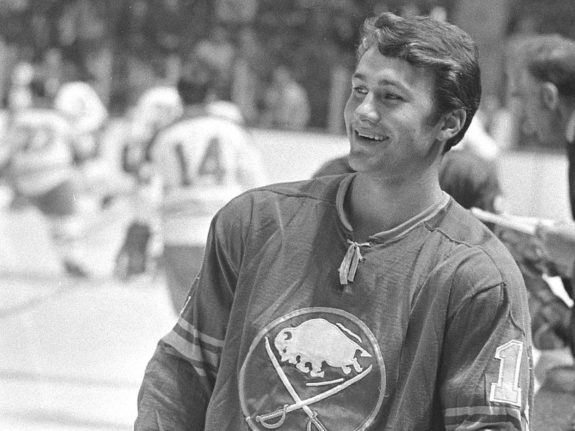

However, had that agreement not expired after 1969, the year that the sponsorship system was fully eliminated, the Canadiens surely would have leveraged the privilege to grab future Hall of Fame center Gilbert Perreault in 1970. Perreault was instead drafted first overall by the expansion Buffalo Sabres, for whom he starred for 17 years – a textbook example of the egalitarian talent distribution Campbell hoped to foster with a draft, one that would nurture new members of a rising league.

The draft was doing just that, morphing and developing with the times, both in concert with political events and the natural growth of the NHL. One of the most significant periods of change occurred in the late 1980s and 1990s, when the fall of the Iron Curtain in Europe and the NHL’s expansion into non-traditional markets – seven teams were added between 1991 and 1999 – increased the importance of the draft. It fed the league’s new reach, eventually placing stars such as the San Jose Sharks’ Patrick Marleau, the Ottawa Senators’ Alexei Yashin and Marian Hossa, the Tampa Bay Lightning’s Vincent Lecavalier and Paul Kariya of the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim into new hockey cities in those franchises’ early days.

Related: 2022 NHL Draft Guide

The North American arrival of Russian and Eastern Bloc talent that began as a trickle toward the end of the Soviet Union’s days, and which accelerated with its breakup in 1991, forever changed the draft and the league. The European influence on the NHL, now more than 30 years along, has made the game faster and more skilled after Canadian players and their physical style had dominated the league since its beginning.

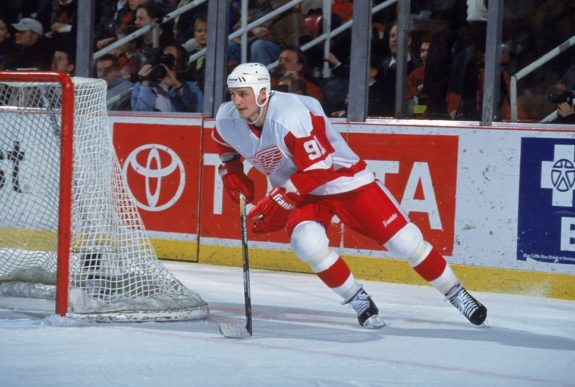

Teams that were quick to recognize the opportunity Eastern European players presented benefited early through the draft. Most notable were the Red Wings, who selected Sergei Fedorov in the fourth round and Vladimir Konstantinov in the 11th in 1989 and Slava Kozlov in the third round in 1990. Along with fellow Soviet stars Slava Fetisov and Igor Larionov, they formed the Russian Five, which helped the Wings to two Stanley Cups and played a significant role in sparking the sea change in the league’s style of play.

The New York Rangers similarly benefited during that time, with Alexei Kovalev (15th overall in 1990), Sergei Zubov (fifth round, 1990) and Sergei Nemchinov (12th round, 1990) playing critical roles in the Blueshirts’ ending of a 54-year Stanley Cup drought in 1994. Kovalev, Zubov, Nemchinov and defenseman Alexander Karpovtsev became the first Russians to have their names engraved on the Cup.

Desire to Eliminate ‘Tanking’ Greatly Influences Current Draft Form

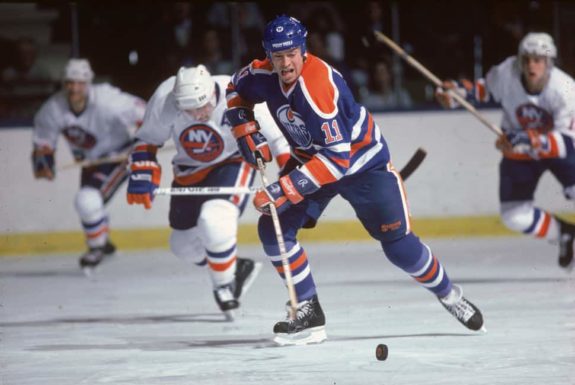

Along the way, the draft has produced the type of anticipation, missed opportunities and lore that fans love to debate and discuss, adding a rich chapter to the NHL’s history. There were No. 1 overall pick busts like Alexandre Daigle, Patrik Stefan and Nail Yakupov, and incredible steals like Nicklas Lidstrom (third round in 1989), Brett Hull (sixth round, 1984) and Henrik Lundqvist (seventh round, 2000). Wayne Gretzky wasn’t drafted, joining the NHL when the World Hockey Association folded in 1979 and his Edmonton Oilers were absorbed by the NHL. Artemi Panarin, among the best offensive players in the league today, never heard his name called during the 2010 draft.

There was the star-studded 2003 draft, among the most talent-laden in history, and the 1979 edition that even without Gretzky produced seven Hall of Famers and numerous other stars who would shape the NHL for the next 20-plus years. There were bleak drafts which delivered few future stars, such as 2012 and the famously talent-bereft first round of 1976.

Gary Bettman, the first man to hold the position of NHL commissioner and who has been in the job since 1993, has never been shy about tinkering with the draft in a quest to keep it as fair as possible. Since the inception of a weighted lottery in 1995, that system has undergone numerous tweaks and adjustments, a reaction to events such as what appeared to be an obvious tanking battle between the Pittsburgh Penguins and New Jersey Devils during the 1983-84 season to get in position to draft phenom Mario Lemieux first overall. The Penguins’ “winning” of that race to the bottom laid the foundation for Stanley Cups in 1991 and ’92.

While the motivation for bad teams to play as badly as possible in order to secure a higher draft position will always provide temptation, the lottery system has done its best to discourage it. The crucial disincentive has been the chances of any team that misses the playoffs, albeit much smaller that that of the bottom feeders, to jump up to one of the top spots – such as the Rangers in 2020, when after a 37-28-5 season, they won the lottery and the right to draft consensus No. 1 prospect Alexis Lafreniere with the top pick.

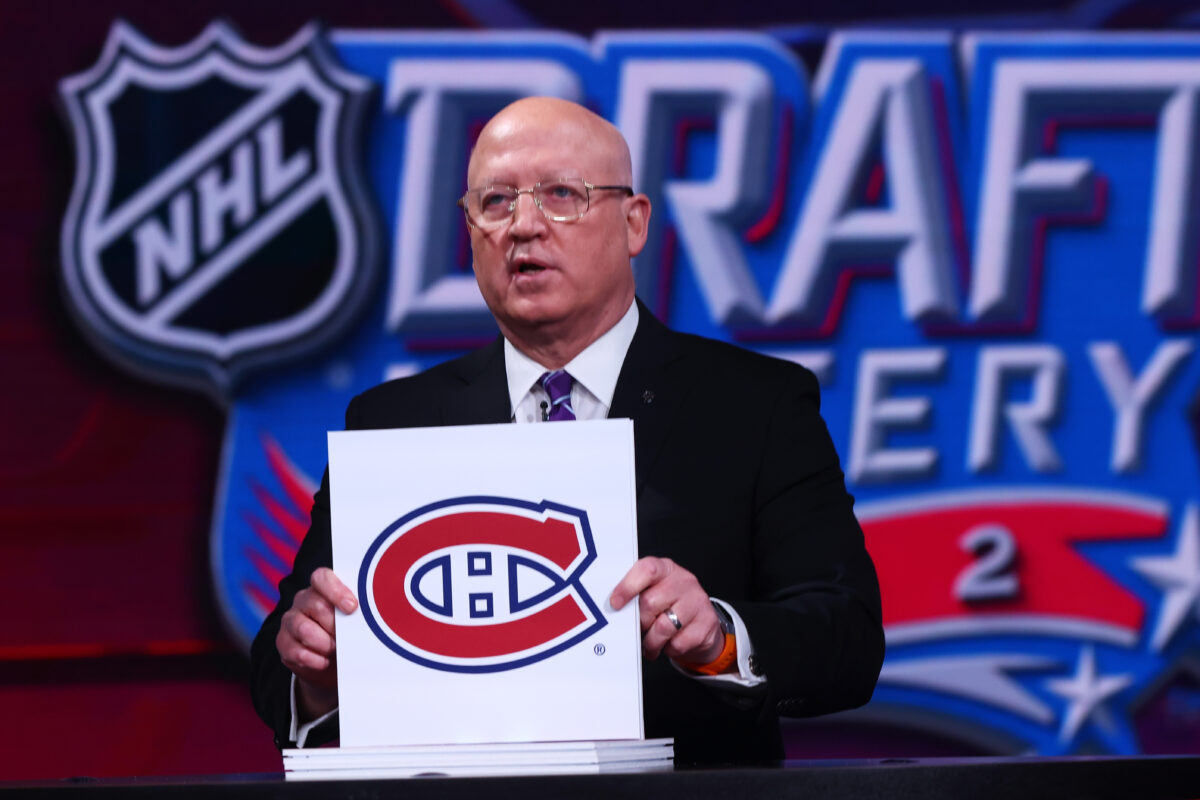

The latest manifestation of the lottery, which debuts this year in the 60th NHL draft, gives better odds and outcomes to the worst teams – in fact, the draft host Canadiens, who went into the lottery with the best chance to capture the top pick, did just that. Other new wrinkles for 2022, such as limiting the number of spots a team can move up to 10 and a prohibition on a team winning the lottery more than twice in a five-year period, speak to an NHL that understands the importance of the draft and is fully committed to maintaining Campbell’s vision: An even and just dispersement of the next generation of stars to its franchises.

The NHL draft will likely never approach the popularity of its NFL counterpart in pomp and viewership, given that league’s place in American culture. Yet the transformation of the NHL draft from what amounted to a mostly less-than-impactful administrative meeting in 1963 to its present-day model, one held in NHL arenas with fans present – and millions more watching on TV or online – is nothing short of remarkable. Reaching that point has been a result of the league’s rise and spread throughout North America, the onset of the media age and the recognized importance among front offices and fans of young building blocks to create a base for sustained championship contention.

Could Campbell have foreseen all of this? Probably not. It would have been difficult for even the most imaginative mind to make such a leap. Yet at its core, the NHL Entry Drafts of 2022 and beyond represent exactly what Campbell was trying to accomplish – forge a mechanism that would be central to allowing the league to become the major sports entity with huge reach that it is today.