There is mounting evidence that NHL players are preparing for a lockout with countless tweets, blogs, and articles hinting that escrow may be the final straw. There is no doubt that escrow is a growing concern, with some calling it the “dirtiest word in hockey dressing rooms.” How will it be the major cause of a lockout?

Escrow Defined

Escrow is when money or assets are placed into an account or held by a third party pending a completed transaction. A wide range of items can be held in escrow including cash, securities (stocks or bonds), and other tangible assets like the title to a car.

The most common use of escrow is when people purchase a home. Here the down payment, or purchase price, of the home is placed into an escrow account along with the title to the property. Once contractual conditions, like inspections, are completed the payment is transferred to the seller and the title is passed to the buyer. It is also not uncommon as part of a mortgage agreement for the bank to set up an escrow account to cover taxes and insurance on the home, including contributions to the escrow account as part of the monthly mortgage payment.

Something important to remember is that the amounts collected in these accounts for things like taxes and insurance are based on a projection of what the homeowner will owe at the end of the year. Because the amount is only a projection and not exact the homeowner may pay more or less than they actually need to over the course of the year. If the actual bills are lower than projected there will be a refund issued. Conversely, if the estimates were too low the homeowner may owe money.

In the NHL the same principles apply. A percentage of NHL player salaries are deducted each pay period and deposited into an escrow account. At the conclusion of the season that money is disbursed to the owners or players based on conditions in the NHL Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA).

Escrow and the Salary Cap

To understand why these escrow accounts are necessary it is vital to understand how the CBA allocates money earned by the league throughout the season.

For the players, their share of Hockey Related Revenue (HRR) is allocated as salary. This is outlined very specifically in the CBA. “Article 50 creates a fixed relationship between League-wide Player Compensation and Hockey Related Revenues, and provides that League-wide Player Compensation will rise or fall in direct proportion to a rise or fall in Hockey Related Revenues.” Section 50.4 (b) goes further, making it crystal clear that under no circumstances can the players’ compensation be more or less than the specified 50 percent share.

At the end of every season, a full accounting is done of league financials and the HRR is calculated. These revenue totals are used to establish the salary cap for the following season.

To calculate the salary cap, the HRR for the previous season is multiplied by 50 percent to establish the players’ share and projected benefits are subtracted from that amount. Benefits in this instance include, but are not limited to, pensions and retirement plans. That value is then divided by the total number of teams in the league.

To project for growth in league revenues, that number is increased by between zero and five percent, often referred to as the “escalator clause”. The new total is established as the Adjusted Midpoint of the payroll range. Once the Adjusted Midpoint is established, the CBA defines the upper limit (the salary cap) and the lower limit (salary floor). These values are achieved by adding 15 percent to the Adjusted Midpoint to determine the upper limit and subtracting 15 percent from the Adjusted Midpoint to set the lower limit.

#NHL and #NHLPA announce next season’s salary cap is set at $79.5 million. Could have gone up to as much as $82 million, players opted for 1.25% growth inflator this season.

— Frank Seravalli (@frank_seravalli) June 21, 2018

To clarify, here is an example with hypothetical figures: The NHL reports HRR of $1.4 billion and projects $80 million in player benefits. The $1.4 billion HRR number is then multiplied by 50 percent to determine the players share of $700 million. Then, the projected benefits of $80 million are deducted for a value of $620 million. This is then divided by the number of teams, 31, for $20 million. The last step is to increase this by five percent, or $1 million, to $21 million which is the Adjusted Midpoint of the payroll range for the following season. Adding 15 percent, or $3.15 million, would determine an upper limit of $24.15 million and a lower limit of $16.85 million.

Why Escrow Is Necessary for the NHL

If the salary cap is based on the percentage of HRR that players are supposed to receive, why is escrow necessary? It is unlikely that player salaries, even if based on historic HRR, will perfectly match the players’ share of HRR for the following season. Escrow ensures that all parties receive the correct share of HRR even when salaries do not perfectly match the players’ share.

There are several important factors that create the disparity, including the manner in which revenue growth is projected. The CBA establishes an increase of 5 percent, with the option for either the league or NHLPA to propose an alternate amount. This “escalator clause” has frequently been modified by the players.

In the season immediately following the implementation of the current CBA, the players voted for a five percent increase. Since then, the growth rate has not been a foregone conclusion. A business cannot predict revenue growth with certainty. Because the salary cap is established based on an imperfect projection then player salaries will differ from 50 percent of HRR.

The growth factor (or cap escalator) was set at just 0.5%, so the NHL's cap growth this summer was driven almost entirely by higher revenues. Playoffs in particular were big I'm told.

A lower growth factor will help control escrow, which is still an issue for some players.

— James Mirtle (@mirtle) June 21, 2018

The most important variable is how teams spend. The only way for the cap structure to allocate the players’ share of HRR precisely would be if the league spent, on average, the exact amount of Adjusted Midpoint. However, on average teams do not spend exactly the Adjusted Midpoint. In fact, the majority of teams spend in excess of the Adjusted Midpoint.

As of July 29, only 12 teams currently have projected payrolls below the Adjusted Midpoint of $69.15 million. Once all NHL rosters are set for opening day there will likely be even fewer. The median NHL team is projected to spend $71.12 million for the 2018-19 season, and the average team payroll is north of $70 million. With the majority of team payrolls outpacing the Adjusted Midpoint, an overage is guaranteed.

Effects and Player Opinion

Paychecks in the NHL contain deductions including for pensions, benefits, and taxes as well as any portion that might go toward agent fees. However, on top of these common deductions, they also include large deductions that go into the escrow account.

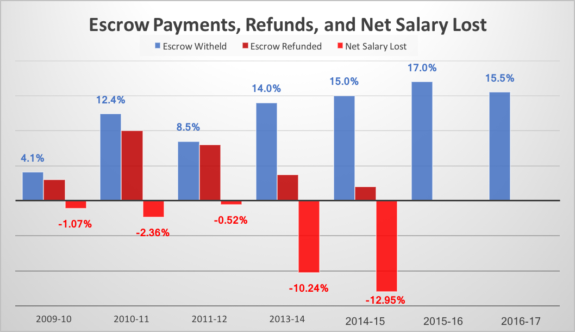

The sticker shock of seeing a drastically reduced payday is hard to swallow, but is even more so when considering how the money in the escrow account is distributed. In years when there is an overage, some percentage of the escrow account is distributed to the owners to ensure the appropriate HRR split. In every year the current CBA has been in place, players have not seen the full amount they paid into escrow returned to them. In fact, in some seasons, players have had as little as 1.6 percent returned to them, with only one season reaching a double-digit percentage return.

Even though this structure is in place to guarantee players and owners get exactly the amount accorded by the CBA, it also creates a perception problem. Because players are not receiving a full refund from the escrow amount, it seems like they are not making the full salary specified in their player contract. It is understandable that a player who is contracted for an amount but, because of escrow, is actually paid roughly 10 percent less, would view this as not getting what they were promised.

Another point of contention for the players is how HRR is calculated. The CBA describes exactly what revenue sources are considered when calculating HRR. Section 50.1 (b) (ii) states that HRR does not include, “revenues from the relocation or sale of any existing Club (or any interest therein) or the grant of any new franchise.”

So, any expansion fees collected by the league, like the $500 million from the ownership group of the Vegas Golden Knights, go to the owners and players still had escrow cut into their pay. Perception is key, and it could seem like players were losing out on money not just once but twice.

What’s Next?

All signs point toward a lockout in 2020-21, especially according to the players. And while escrow may not be the only reason, it is going to be a significant contributing factor. For the players, the current situation is untenable and any new agreement cannot be reached without some significant changes. So, what can be changed to eliminate these concerns?

One option would be to remove the growth factor, the escalator clause, from the salary cap structure. If the salary cap for a given season was determined not by a projection of expected revenue but rather the actual revenue from the previous season, the need for such an extensive escrow would be reduced.

Although, not all players may like this change. Free agents, in particular, would see a significant loss. Without the escalator, the cap would likely increase at a slower rate, allowing teams less cap space to offer big contracts to players on the open market. This disconnect between players has already been a challenge when the NHLPA has had to decide what the escalator should be in a given year. There is no reason to expect unity on the matter during upcoming CBA negotiations.

Another option that would appease some players, but not others and certainly not the owners, would be to use the revenue projections to set the upper limit instead of the Adjusted Midpoint. If calculated this way, the likelihood of players being overpaid relative to their share of HRR is reduced and, therefore, so is the need for escrow. For players under contract, this means they will have significantly smaller escrow deductions.

Just like removing the escalator altogether, free agents would see smaller contract values since this would likely mean smaller increases to the salary cap, making it harder for teams to hand out large salaries. The league also may not be keen on this, as it would increase the odds of a season when players are underpaid relative to their share of HRR and would force owners to write checks to make up the difference.

Yet another option to reduce or eliminate the need for escrow is to remove the link between player salaries and HRR altogether. For players, this would make the value of their contracts absolute. But because revenues are impossible to perfectly predict, both sides would risk losing out significantly as the league’s financial health ebbs and flows.

Regardless of what may happen going forward, for the time being, escrow is here to stay and undoubtedly, will be one of many contentious elements of the current CBA that could contribute to another lockout.