The Olympics and its substance-related suspensions have brought to the forefront a common question in sports, one which hockey and NHL fans generally prefer to avoid contemplating. It is no secret that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and its notoriously harsh protocols regarding performance enhancing substance testing are substantially more restrictive than the NHL’s.

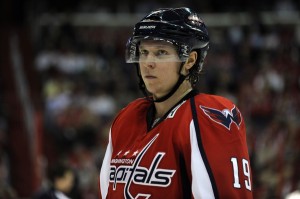

Nicklas Backstrom’s now-infamous failed test that was ultimately ascribed to allergy medication is, of course, not of any concern here for several intuitive reasons.

The case of Vitalijs Pavlovs, the Latvian hockey player whose expulsion from the Olympics occurred after his team had already been eliminated by Canada, is a little more disquieting. He tested positive for methylhexaneamine, a stimulant that is significantly regulated or otherwise illegal for safety-centric reasons in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and numerous other nations. In defending himself, Pavlovs claimed that a doctor for his KHL team in Latvia recommended a food supplement which happened to contain the drug.

It is exceedingly unlikely that we will ever discover whether or not Pavlovs was guilty of something more than simple negligence, but it does not necessarily matter. In a vacuum, Pavlovs’ case is unremarkable and unimportant; he is but one athlete amongst many, and while methylhexanamine is considered to be a performance enhancing drug, it is unequivocally on the low end of the spectrum.

Of course, matters have since become remarkable and important; the news broke on Friday afternoon that a second hockey player on Latvia’s national team tested positive for a banned substance. A one-time occurrence can simply be a fluke; a two-time occurrence is much more likely to reflect a trend.

2014 Olympic hockey is firmly in the rearview mirror, but the situation with Team Latvia brings to light a question that hockey fans would be foolish not to ask.

“Could use of performance enhancers quietly be a rife reality in the NHL?”

Compelling, isn’t it? The initial response of many fans is “absolutely not.” Those who hold such a position may (quite reasonably) cite that the NHL has had to hand out only one suspension for a banned substance with its PED program in effect1. Others in agreement may add that some PEDs unavoidably sacrifice agility in favor of strength, which would be a counterproductive exchange in light of hockey’s powerful emphasis on the former.

Before examining the question in depth, however, we first need to understand the present state of drug testing in the NHL.

The NHL PED Program

The league’s players receive yearly education regarding banned substances and the precise rules and regulations of the NHL’s substance program. Testing and any ensuing potential discipline cannot occur until the player has had one of these orientation sessions.

Every NHL team undergoes “team-wide no-notice testing” once during training camp as well as at a random point during the regular season. Throughout the regular season and playoffs, individual players are randomly tested without notice. These tests do not occur on game days.

During the offseason, a maximum of 60 randomized individual tests are conducted (note that this indicates the possibility of less than 60 as well). There is also a provision regarding the NHL’s right to initiate a non-random test if there is “reasonable cause” to suspect that the player in question used a banned substance within the preceding year2.

Addressing the NHL PED Question

The question itself one more time, for reference: Could use of performance enhancers quietly be a rife reality in the NHL?

It would be unjust and excessively partisan of me to launch into an explanation of why I believe the answer could be “yes” without first outlining the arguments of those who believe the opposite. We thus begin with a brief summary of the most common arguments in favor of the position that the NHL definitively does not have a problem with performance enhancing drugs.

The NHL PED Question: “Absolutely Not”

The chief contention of this school of thought has already been discussed. There has only been one suspension related to performance enhancers in the NHL, a far cry from the MLB (13 in the recent Biogenesis scandal alone), NFL (the eminently suspicious Seattle Seahawks), and even the notoriously lax NBA (8 in its history).

This line of thinking holds undeniable weight when taken at face value. The prevailing wisdom, asserts the “absolutely not” camp, is that there would be more than a meager one instance of a player getting caught if PED use was truly a problem. Even the NBA’s advanced notice tests have yielded eight suspensions; if this was even a small issue in the NHL, shouldn’t that number be at least a little larger than merely one?

An additional argument lies in the (non-perfect) inverse relationship between a common goal of PED usage and a generally crucial hockey skill; that is to say, the inverse relationship between strength and agility. A decline in quickness does not accompany every increase in strength by any means; indeed, under normal circumstances, it rarely does. But performance enhancers fall outside the realm of “normal circumstances,” and the inverse relationship becomes much more of a reality when the athlete is using unnatural means to augment strength. Whatever benefits PED usage would bring, then, would be outweighed by its agility-sapping costs.

A final bit of support sometimes offered by those holding the “absolutely not” attitude is the affirmation that NHL players are fundamentally different from the athletes in other sports in which banned substance use is more prevalent. To briefly depart from being charitable to the opposition’s argument, this particular stance is far too often fueled by outright racism. It has no means of justifiable support, and as a result I see no need to discuss it in the following paragraph3. A conclusion that stands on false premises is inherently valueless.

The NHL PED Question: Attacking the “Absolutely Not” Argument

The position as lined out above sounds deceivingly attractive. Counterpoints to each of its stances are readily available.

Taking the lack of PED suspensions as evidence of there being no PED problem is to fall victim to a fallacious trap of equifinality4. There are multiple means to the single suspension end, and “the NHL doesn’t have a PED problem” is simply one of many. Perhaps the lack of discipline is attributable to the fact that the league never used to test players during the offseason; indeed, this was the case for all offseasons prior to 2013. The NHL’s new CBA has taken measures to correct this, but they are limited; as discussed, only up to 60 substance tests can be conducted, which encompasses less than 10% of the league’s total players. There is also no guarantee that all 60 are used each summer.

Another possibility involves a far simpler approach: maybe the NHL’s testing is just easy to beat. It is impossible to say for sure, but this is precisely the point; it is equally impossible to label the lack of suspensions as an indication of a PED-free culture. All I intend to do is purport the possibility of PEDs being more widespread in hockey and the NHL than some want to believe, and this is enough to cast doubt upon the “minimal suspensions means minimal PEDs” line of thinking.

The argument based on the dichotomy of strength and agility is also flawed. While I would grant that it likely crosses muscle mass and strength-building anabolic steroids off the list (in spite of Sean Hill), this is only one sector of the PED industry. Blood doping, human growth hormone, and erythropoietin are but three examples of performance enhancers that would offer significant gains without notable accompanying declines in on-ice agility or mobility. Make no mistake, there exist a slew of hockey-relevant PEDs. The question is not one of availability.

Having illuminated the shortcomings of the “absolutely not” response, we can now delve into a discussion of why the use of performance enhancers could conceivably have a niche in the NHL5.

Answering the NHL PED Question

Could use of performance enhancers quietly be a rife reality in the NHL?

At this point it is patently obvious that the most appropriate answer is “yes, it could be,” or any other derivative of “maybe.” There are many ways to justify this.

To begin with, we have already discounted the “absolutely not” hypothesis. Logically speaking, if the answer “no” is out of the equation, then every remaining possibility involves varying levels of “yes.” Put differently, by showing that “absolutely not” cannot be the case, “could be” is necessarily the case6.

There are, of course, much more interesting avenues to discuss than logic. Let us move on.

The NHL does not currently test for human growth hormone (HGH), and it is not presently known exactly when it will start to. Concerning the matter, the league’s deputy commissioner Bill Daly said, “While this is an issue that we are committed to working through with our Players’ Association, it’s not an area that we believe we have any material issues or problems with, and it’s certainly not an issue that we feel compelled to be ‘leaders’ on.”

A somewhat disturbing attitude, would you not agree? “Blasé” and “apathetic” come to mind — not exactly confidence-inspiring. As long as HGH remains untested, it constitutes an enormous question mark.

We have also seen a number of NHL players recover from heinous injuries at an almost superhuman rate, against all odds returning to the ice before or at the very beginning of their already-optimistic injury timetables7. One or two of these situations is not necessarily suspicious, but they are becoming more common seemingly by the year8. Needless to say, a laundry list of substances could be responsible9.

Of PED use across the league, Jonathan Toews has said, “…it would be naive to say that there’s no one in the NHL that is trying to get the edge in that fashion.” This coheres with what we know to be true at a general level of professional athletes: the vast majority are incredibly competitive, and performing well relative to one’s peers almost inevitably yields superior financial compensation. We can presume that nearly all NHL players are constantly seeking to acquire a competitive advantage, after all. Performance enhancers offer such an advantage, and the potential benefits are not inconsiderable. Does it not seem plausible that some decide to take the risk?

In his autobiography, former NHL player Georges Laraque declared that he had knowledge of a number of players who used PEDs while he had been playing.

Richard Pound, once the president of the World Anti-Doping agency and a former IOC member, made headlines in 2005 when he stated that he believed past or present use of performance enhancers stretched to as much as 33% of the league’s players. I would be remiss not to mention, however, that he based his opinion largely on anecdotal evidence.

The issue of PEDs in the NHL is, suffice it to say, incredibly murky.

But could they quietly be a significant part of the NHL player culture?

Unquestionably.

—————————————————————————————————————

1 Sean Hill tested positive for the anabolic steroid boldenone and was subsequently suspended for 20 games in 2007.

2 All information was paraphrased and found in the NHL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement, which can be accessed here if you have an undying love for incredibly dense legal documents or are just curious.

3 If anyone wishes to debate the merits of the “NHL players are different” claim and has a genuine, quality reason to offer, I am open to doing so via some other medium. After consideration, I thought it best to remove any such discussion from the article itself.

4 “Equifinality” might be my favorite word in the English language.

5 I want to emphasize that I am speculating only. Suggesting that PED use could be commonplace in the NHL is vastly different from asserting that it definitely is. You’ve probably noticed my aversion to using absolutes in this piece — there’s a reason for it!

6 LSAT preparation leaves an indelible mark on all who undertake it.

7 This is not restricted to just the NHL by any stretch.

8 In keeping with the spirit of footnote #5, I don’t think it’s appropriate to directly reference the players’ names.

9 Insulin-like growth factor 1, an ingredient in deer antler spray, was discussed ad nauseam in 2013 in the context of injury recovery.

Follow Sean Sarcu on Twitter or add him to your network on Google.

Defensible yes, convincingly so, I’m not sure. But I doubt baseball has ever cared about the health consequences of PEDs, I think the major affront was in the dismantling of their treasured record book. Hockey doesn’t have those sacred numbers like 61. Although would it be troublesome if we learned that say Marty Broduer juiced his way to so many slots in the record books? Goalies who he passed who hadn’t juiced might be more than a little upset.

Well done Sean. For years and years you could hear people in baseball– from executives to fans– say that PEDs wouldn’t help a guy play baseball better, they wouldn’t help a guy hit the ball further, that in general they offered nothing towards the sport’s necessary skill set. We now know just how ludicrous that line of thinking is. And that’s every reason to throw out any argument that PEDs would somehow detract from a hockey player’s game because they’re the kinds of a priori arguments that simply give everyone a box of sand to bury their heads in.

Thanks Ross.

Yep, don’t think there’s any doubt there exist plenty of performance enhancers that would fit their namesake as far as hockey is concerned. It seems like the league is happy to largely leave the issue alone and stay out of the news, which is probably defensible.