When the Erie Otters dusted off the Mississauga Steelheads in five games to win their second OHL title, no one was surprised. In fact, some expressed surprise that the series was as close as it was, with the Otters outscoring the Steelheads just 17-12 and Mississauga pushing Erie to overtime in the decisive game in addition to claiming their one win.

Despite Mississauga’s strong showing, the 2017 OHL Final was just another instance of what has become one of the most reliable trends in the modern OHL: the Eastern Conference simply cannot compete with the Western Conference.

The West is Best

The Otters’ triumph marked the 14th time in 16 seasons that a Western Conference team took home the J. Ross Robertson Cup as OHL champions. But it’s not just the playoffs. This year saw the Western Conference put together its most dominant regular season performance ever. The league’s top five teams in points and goal differential (GD) were all in the West, while the conference outscored their Eastern Conference opponents by 299 goals in 216 inter-conference games.

This is a massive disparity. If we adjust that goal differential to a standard 68-game OHL season, the average Western Conference team in 2016-17 would have had a plus-94 goal differential if it only played Eastern Conference opponents. For comparison’s sake, last year’s 105-point, first overall Otters club had a goal differential of plus-86, while this year’s London Knights squad (99 points) finished at plus-95.

Amazingly, these stats aren’t only skewed by the West’s top teams. Consider the Kitchener Rangers, who finished sixth in the West, who had a minus-7 GD on the season overall, but against the Eastern Conference was a robust plus-22 in 20 games. That prorates to a plus-75 GD over a 68-game season—not quite the 2015-16 Otters, but still excellent. Kitchener’s success wasn’t just on paper, either: they put together a 16-3-1 record against the Eastern Conference this year despite playing below .500 (20-24-4) versus the West.

The Saginaw Spirit, who missed the playoffs in the West, were 12-5-3 against the East with a plus-15 GD. Even the woebegone Guelph Storm, who finished last in the West with a paltry 49 points, went a respectable 10-9-1 against the East.

Two Decades of Dominance

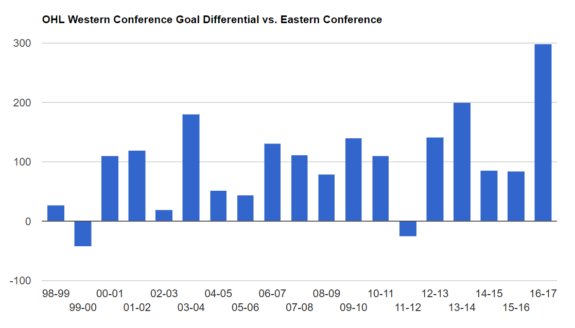

An examination of the goal differential numbers since the 1998-99 season—the beginning of the twenty-team, two-conference OHL—shows that while this year’s results are a historic outlier, the previous few years weren’t much better:

The West has outscored the East in 17 of the 19 seasons since the two conferences were formed, and often by a considerable margin. (For the morbidly curious, the Western Conference has outscored the Eastern Conference by 1868 goals in total.)

While there have been scattered seasons where the disparity was relatively small, these were almost all clustered in the first half of the timeframe. Five of the six best performances in the East were in the first eight seasons of the format (through 2005-06), with the surprising 2011-12 season as the only exception, in which the Eastern Conference outscored the Western Conference by 26 goals.

In other words, the West’s incredible run of championships isn’t just a case of the East choking in the Final. Western Conference teams have also won the Hamilton Spectator Trophy, which recognizes the team with the highest regular season points total, in 17 of the 19 years of the present format. And the disparity is worsening.

This trend is more apparent once we consider the historic ineptitude of the Mississauga IceDogs, who joined the league in 1998-99 and promptly put together an aggregate record of 16-168-11-9 over their first three seasons. The IceDogs were a collective minus-243 against the Western Conference over that period, including a ridiculous minus-95 in 24 games in 1998-99. By comparison, the Brampton Battalion, the IceDogs’ expansion cousins, were just minus-30 against the East that year and made the playoffs in their second season.

Much of the inter-conference disparity in the first few seasons of the two-conference format can be chalked up to the IceDogs, who were putrid. For example, if we were to remove the league-worst IceDogs and the Battalion from their respective conferences for the 1998-99 season, the East’s margin over the West would shift from minus-27 to plus-20. This suggests that the West’s GD margins against the East in the late 90s and early 2000s are something of a mirage, a product more of the quirks of league expansion (and perhaps then-IceDogs owner Don Cherry, who famously refused to allow European players on the team for the first three years of its existence).

In contrast, the last eleven years of Western Conference dominance look real. While there have been a handful of weak teams over the past dozen-odd years, none of them was as overmatched as those turn-of-the-millennium IceDogs squads, and some of the worst, such as the 10-win, 2011-12 Erie Otters, hailed from the Western Conference.

Beyond the Numbers

There’s no question that there’s been some luck involved in the West’s amazing streak. The Mississauga Majors outscored the Owen Sound Attack 28-21 in the 2010-11 OHL Final but lost three games in overtime and the series 4-3. The Barrie Colts lost Game 7 of the 2012-13 OHL Final on a last-second goal by London’s Bo Horvat to blow a 3-1 series lead. Both series could have gone either way.

As the GD data makes clear, though, the conference imbalance is so much more than just the OHL Final. It’s real, it’s pervasive, and it has wide-ranging implications for the League, from the perspective of competitive balance to fan engagement to player recruitment. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be looking at why this imbalance is so severe, what kind of impact it’s had on the League, and what can be done to fix the problem. Commissioner Branch, take note.