Patrick Kane’s seven seasons in the NHL have had more highs than many players experience in careers that last twenty years, but he has also been through more than his fair share of low times. The Kane that Blackhawks fans see today is starkly different from the wide-eyed and immature 19 year-old he was in 2007-08, both on and off the ice.

Such changes, of course, do not occur overnight; Kane had several hiccups along the way, most of them around the middle of his career. We begin with his rookie season.

2007-08: Patrick Kane and the Rebirth of a Franchise

The Blackhawks were less than an afterthought prior to 2007-08, absent from the playoffs for four straight seasons and having failed to qualify for eight of the last nine. Chicago’s management team had driven the team into the ground, and continued to dig the hole deeper with each and every terrible season and non-televised home game.

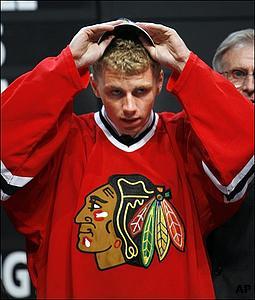

An influx of young talent was on the way, fortunately; namely, a certain captain who would wear No. 19 as well as a future Stanley Cup-winning goal scorer to whom the number 88 has become nearly synonymous. 2007-08, or the beginning of Jonathan Toews and Patrick Kane’s NHL careers, marks the true beginning of the Blackhawks’ return to relevance.

Chicago won the 2007 draft lottery — Kane’s draft year — despite having just an 8.1% chance of doing so; perhaps this was some karmic retribution for losing out on Evgeni Malkin in 2004. The then-rather-diminutive Kane was immediately a standout in the team’s prospects camp, held in July less than a month after the draft.

Kane began the 2007-08 season by promptly erasing any questions about whether or not his small stature would preclude him from NHL success, compiling 13 points in his first 9 games. Playing in a 10th game would mean a year being burned off his entry-level contract, not unlike the present situation with Teuvo Teravainen.

Needless to say, sending Kane back to the OHL’s London Knights wasn’t even discussed.

He finished the year with 21 goals and 51 assists, and ran away with the Calder Trophy as the league’s best rookie. Chicago just missed out on a playoff spot, but saw its attendance spike midseason. Fans were returning to the United Center again, not only due to the death of long-despised owner Bill Wirtz but also because of the fresh, exciting product the suddenly interesting Blackhawks provided on the ice.

2008-09: Patrick Kane’s Successful Season, Disastrous Offseason

The 2008-09 season constituted an enormous step forward for the franchise. No longer an afterthought, the young Blackhawks — led by Toews and their most dynamic offensive player, Kane — became one of the hottest tickets in Chicago just as they remain today. Two years prior, suggesting Chicago as a host for the Winter Classic would have been anathema; in 2008-09, it was a brilliant idea and smashing success.

On the ice, Kane didn’t progress in terms of raw production, but he was a much more consistent scorer; he went through far fewer lengthy goal and point droughts than he had in 2007-08. Kane’s defensive play took a small step forward, as he no longer flew the defensive zone looking for a breakaway pass — a nasty tendency from the previous year — and was a slightly better positional winger. Still, he remained likely the worst own-zone player on Chicago’s roster, and his defense would become a sort of pet project for Joel Quenneville.

Chicago had its best season in more than a decade, easily qualifying for the playoffs and ranking as one of the league’s top teams in nearly all measures. Kane was probably the team’s best forward during that postseason, establishing himself as a big-game player almost immediately.

On the first video: Here we have a fun, forgotten storyline… something that was a hot topic in the media at the time but has since been buried in hockey’s vast historical archives. After Game 1 of the Canucks/Blackhawks series, Vancouver defenseman Willie Mitchell said, “where [Kane] is going to do his damage is on the power play. He is not a guy who is really going to hurt us [at] even strength.”

Naturally, then, all three of Kane’s goals in the series-deciding Game 6 came at even strength. Celebrating in the locker room afterward, Kane exclaimed how happy he was to have gotten “a wake-up call from old Willie Mitchell over there.” A star was being born.

On the second video: It depicts a game which would ultimately be the last of the 2008-09 season for the Blackhawks, a Game 5 loss to the Detroit Red Wings. They were outclassed by the far more experienced Wings, and it was evident from the start of the series. Kane was one of the few forwards on Chicago’s roster that managed to make a noticeably positive impact.

Unfortunately, matters did not stay rosy for Kane for very long. Vague rumors of an immature kid with a weakness for the party lifestyle were difficult to miss. Anecdotal stories from Chicagoans labeling Kane as, behaviorally speaking, little more than a spoiled child popped up with a disturbing degree of regularity.

These rumors and stories gained no real traction; such is usually the reality of things based purely on hearsay. Most if not all likely had no basis in fact whatsoever; for that reason I see no justification for lending credence to them by specifying their contents.

Still, where there was smoke, there was fire. Kane was arrested in Buffalo on August 9th, 2009, alleged to have punched a cab driver when he claimed not to have twenty cents in change to give back to Kane for the $14.80 fare. The situation turned into an unmitigated mess, and the details of what really happened have never been made clear; there was speculation that the driver, Jan Radecki, may have locked the doors to keep Kane (and his cousin, also present) from leaving the car before paying, speculation that Kane (underage) was intoxicated, and speculation that if any punch occurred, it may have been the cousin who threw it and not Kane himself. Radecki himself did not have a sparkling clean criminal history.

Let me stress again that the details remain incredibly murky, and that I am in no way claiming anything I have labeled “speculation” to be fact. Ultimately, the public will be left in the dark as to precisely what happened, why it happened, and who was actually at fault, but one thing is true regardless: Kane put himself in a difficult position, and he paid for it.

His reputation was sullied for a number of years. Bizarre rumors rose out of Chicago that the Blackhawks were looking to trade Kane to Pittsburgh. A small faction of Blackhawks fans turned on Kane entirely, not wanting to see a “cabbie puncher” don the jersey ever again.

Whatever really happened in the cab that night, the hockey world thereafter viewed Kane in a considerably more negative light. He was no longer just an exciting young forward, but an exciting young forward with imposing off-ice questions, a dubious work ethic, supposed “behavior and self-control problems,” and a party obsession.

It sounds overdramatized, but this is the story just as it transpired. The court of public opinion is not kind and is exceptionally prone to sensationalizing. Kane made a mistake and he paid for it ten times over.

2009-10: Shirtless in Vancouver and a Stanley Cup Winner

2009-10 was Kane’s best statistical 82-game campaign to date, as he racked up 30 goals and 58 assists for a career-high 88 points. He seemed primed to shatter those numbers at one point earlier this year, but a long slump followed by a knee injury have combined to eliminate that possibility.

Of special note in 2009-10 is that Kane’s previously terrible defensive game (comparable to what present-day Alex Ovechkin offers) made a titanic leap up to “average.” I speak with no sarcasm here; the difference a year made was utterly striking. A player who just the previous year had been one of Chicago’s worst along the boards in his own zone was now one of the best. Laziness on the backcheck turned into genuine exertion, perhaps evidenced no better than by his Herculean effort to take a scoring chance away from Sidney Crosby in the 2010 Winter Olympics (regrettably, there doesn’t seem to be a readily accessible video of the play).

If it hadn’t happened already, the 2009-10 playoffs were Kane’s true coming-out party as a game-breaking, unequivocal star; he compiled 28 points in 22 games and belonged in the discussion for the Conn Smythe Trophy every bit as much as its eventual winner (Toews). A majority of his 10 postseason goals came in the biggest and most important of moments.

Many forget how close the Blackhawks came to facing elimination in the first round in the 2010 playoffs. If Kane doesn’t score that goal, Chicago heads back to Nashville for Game 6 down 3-2 in the series. They may still have pulled it out in 7, but that was a very solid and underrated Predators team; the odds would have been decidedly in their favor. Fortunately for the Blackhawks, Kane made any such discussion moot.

There was another memorable goal that spring. You may have seen it.

On second thought, never mind. Almost nobody did.

And the parody too, because why not.

Kane permanently cemented his status as a “clutch” performer, and effectively became a legend in Chicago sports. It was the Blackhawks’ first Stanley Cup win since 1961. A franchise that had suffered through a long and brutal dark period matched in severity only by Harold Ballard’s Maple Leafs had finally escaped the sticky vortex of insignificance.

While 2009-10 was a decisively positive year for Kane, he nevertheless made the news a handful of times for some less-than-desirable reasons. In late January during the regular season, Kane — along with John Madden and Kris Versteeg — had a somewhat infamous night out in Vancouver while in town for a game against the Canucks, which the Blackhawks lost 5-1.

The whispers, always there but quieted somewhat due to Chicago’s success on the ice, reared their head once again. Words like “maturity” and “professionalism” once again became part of the everyday Kane-related vernacular. Certainly, there is nothing terribly wrong about a 22 year-old having some fun out on the town… but this was Patrick Kane, not some average, senseless college student. He — as with any professional athlete who has had past troubles — was and is held to a lofty standard, and any behavioral departure from these expectations is breaking news. That this standard is grossly unfair is hardly surprising; John Madden, who I mentioned as being part of the group’s adventurous night, was married with two children at the time (and still is, presumably). There wasn’t so much as a peep about him.

The double standard is cruel, but it undeniably exists. Numerous players were clearly intoxicated at Chicago’s Stanley Cup parade in June 2010, but Kane was the only one who received a hefty amount of press for it. To some degree — indeed, a large degree — he had only himself to blame, but our society’s hawklike focus on those who have erred in the past is poisonous and reeks of confirmation bias.

While Kane appeared to be more or less the same somewhat immature young adult as ever off the ice in 2009-10 (what a crime, huh?), we should not understate the substantial leap forward he took on the ice that same year.

2010-11: Patrick Kane’s Status Quo

This was, biographically speaking, the most unremarkable season of Kane’s career. His production (27 goals and 46 assists in 73 games) didn’t quite reach the heights of 2009-10, but it was still quite strong especially in light of the fact that scoring across the league was trending downward.

Defensively, he stayed largely on the same level as the previous season, albeit with slightly less consistent effort on the backcheck. The playoffs came and went quickly, with an overmatched Blackhawks team falling to their rivals from Vancouver in a Game 7 that would have been a blowout if not for Corey Crawford. Point-wise, Kane’s postseason wasn’t bad, but he wasn’t anywhere near as impressive as the prior spring and seemed intimidated at times by the Canucks’ Alexander Edler.

Of note is that for the first time in three seasons, Kane stayed completely out of the “troubled athlete” spotlight. Some professed that maybe he had finally reached that nebulous stage of societally-defined “maturity,” that maybe he had achieved a newfound level of respectability and honor. Maybe the worst was behind him.

Putting aside any qualms about society’s trite expectations and demands, there is at the very least no doubting this: the worst was not behind Kane.

2011-12: Out of Position, Out in Wisconsin

There’s no sugarcoating it — 2011-12 was a dreadful year for Patrick Kane, both on and off the ice.

His 66 points in 82 games coincided with by far the lowest single season points-per-game ratio of his NHL career. What’s more, Kane would go weeks at a time without making an appreciable difference in games; the points he did manage to pick up during those stretches were often due more to the work of teammates than himself.

Kane played more than half the season at center instead of on the wing, out of position due to Chicago’s dearth of talent down the middle after Jonathan Toews. It was an experiment that was by all accounts spearheaded by Joel Quenneville, who believed that Kane would be able to handle the defensive duties and would benefit from the position switch because he would have the puck more.

The results of the experiment were mixed at best, destructive at worst. Kane proved Quenneville correct in that he was certainly capable of playing center at the NHL level and was still a net positive presence on the ice. Still, the added responsibilities in the defensive zone inherent to playing center rather than wing forced Kane to alter his offensive game. He no longer got to lead attacking rushes as the puck handler, because his positional duties essentially mandated he be the trailer instead. The problem with this is obvious; Kane is at his best with open space and options, and those two things come into play most significantly on rush opportunities. Take away those rush opportunities, and Kane’s best assets are rendered mostly useless at even strength.

To his credit, Quenneville realized that the experiment wasn’t working, and Kane was slotted back at wing around the middle of the 2011-12 season. Unfortunately for everyone involved, however, Joe Thornton punched Toews in the back of the head during a scrum (an uncharacteristically dirty play by a usually respectable player), and Chicago’s captain was knocked out of the lineup by the aftereffects several games later. By necessity, Kane was moved back to center, and the offensive problems persisted.

The playoffs that year were the worst ever for both Kane and the “post-resurgence era” Blackhawks. His four points in the six-game series loss to the Phoenix Coyotes — an unimpressive total in its own right — actually understate just how invisible Kane was. It may very well have been the worst six game stretch of his NHL career.

In fairness, most of the team was every bit as bad. Patrick Sharp had one point and was shooting wide of the net like clockwork, Marian Hossa didn’t register a goal or assist in three games before beginning his offseason early due to an egregiously predatory hit by Raffi Torres, and Corey Crawford — typically a great playoff performer — had one of the worst playoff series by a goaltender in recent memory. Still, the fact that most of the team fell flat hardly excuses Kane for falling woefully short himself. Things would devolve only further that offseason.

2011-12 Offseason

Kane celebrated Cinco de Mayo (May 5th) in Wisconsin, engaging in a notorious bender and leaving behind plenty of picture evidence of his very obvious and very public inebriation. As you might expect, a slew of eyewitness accounts flew in, many of them describing Kane in various embarrassing positions as well as one that even claimed he became violent towards a woman. As always, of course, I would be remiss not to note that the truth of such anecdotal stories is and will always be questionable. Nonetheless, some facts were abundantly clear: Kane was embarrassingly drunk, acted with profound recklessness, and his behavior reflected horribly on the Blackhawks as a franchise.

It was one thing to snap a picture or two with a few women in the back of a limousine, shirtless or not. Kane’s adventure in Wisconsin was quite another. Two months afterward, he called the ordeal “embarrassing” repeatedly at Chicago’s team convention, acknowledging that “things probably got a little bit out of control.”

According to Adam Jahns of the Chicago Sun-Times, the Blackhawks were fed up, and some within the organization were calling for Kane to seek help for a (presumed) drinking problem. A source from inside the organization said, “[Kane’s] obviously got some issues. How many more times can these things happen? It’s a much bigger thing than some photographs in a 48-hour window.”

The fall from grace was startling. Less than two years earlier, this same person — this very same Patrick Kane — was almost larger than life; he had just scored a goal to bring the Stanley Cup back to a championship-starved city, completely revitalized a dying franchise, and guaranteed himself nearly legendary status in Blackhawks lore… the cabbie incident notwithstanding.

Yet here he was, reduced to a bungling mess, coming off an exceedingly disappointing season, and forced by his own ill-conceived actions to talk far more about his offseason drinking romps than what he did to improve as a player. Things could hardly get much worse.

Thankfully, they did not. It would seem that the proverbial light switch finally flipped on at this point. His comments after the Cinco de Mayo escapade indicate as much. Per Adam Jahns: “It’s not fun. That’s not really the person I am. I think the people that are closest to me really know who I am and what I’m about and what I want to bring to this world. That’s definitely not something I want to pride myself on, and the image that I have right now is something I can only strive to get better. That’s not who I want to be. I want to be someone who can be a role model to kids and to everyone for that matter.”

As for what Kane needed to do himself: “I’m not going to really get into details, but there are definitely some precautions that you want to take, and I’m handling that myself.”

By all accounts, Kane has been the equivalent of an off-ice angel since (as much as a hockey player can be, anyway). If we are going to blame him for his past mistakes — and we are — then we also need to praise him for owning up to them, growing past them, and becoming a better person for it. Too often, our society focuses exclusively on the negative side of the equation; there is no room given for redemption or improvement. Kane’s mistakes were silly and wholly unnecessary, but they were also a far cry from some of the more morally reprehensible things that professional athletes in the same position as him have done.

With all that said, we can now move on to discussing Kane’s role on a historically great Blackhawks team.

2012-13: Patrick Kane’s Unwavering Focus

Unwavering focus on hockey, that is. From the first game of the shortened campaign against Los Angeles until the last tilt against the Boston Bruins in Game 6, Kane was quite plainly locked-in. Had it been a full 82-game season, he would have had a great shot to break the career high in points (88) that he set in 2009-10. In any case, he led the entire (stingy) Western Conference in scoring with 23 goals and 32 assists in 47 games.

The Blackhawks had a season for the ages, going an absurd 21-0-3 (with the three “losses” coming via the shootout) in the first 24 games of the year. Kane started hot, putting up 9 points in the first 5 games. He was consistently productive, ending up on the scoresheet in 35 of 47.

To match Toews’ accomplishment from 2010, Kane nabbed the Conn Smythe Trophy in 2013 as Chicago won its second Stanley Cup in four seasons. Kane claimed that Crawford deserved the award more than him, something the “old” Patrick Kane probably never would have even thought to say (in truth, it could have justifiably gone to Kane, Crawford, or Duncan Keith).

And, because this is Kane we’re talking about, there were the big-game moments.

Another hat-trick, another series-ending goal for Patrick Kane. News at 11.

This is the best video I could find of the play, altough it’s not quite perfect (it starts a tad late). Kane’s role in Bryan Bickell’s game-tying goal in Game 6 isn’t talked about even close to enough. He weaves his way through four Bruins to establish Chicago control in the offensive zone (four!).

What happens if Kane doesn’t try to be the hero there? What happens if he makes the “correct” hockey play, dumping the puck in after he sees that he’s vastly outnumbered? There are no guarantees, but the odds are that the Bruins would have held on to win Game 6, setting up a decisive Game 7 in Chicago. Perhaps the Blackhawks don’t win the Cup at all.

Taken as a whole, 2012-13 went about as perfectly as possible for Kane, and the credit for that goes solely to him.

2013-14: To Be Determined

After going scorched earth for the first few months of the year, Kane entered an extended scoring slump that evened out what had previously been some crooked numbers. His regular season ended on a flukey, unfortunate play near the boards against St. Louis which resulted in a grade 1 MCL sprain. In the end, the production more or less matched Kane’s established career norm — 29 goals and 40 assists in 69 games, or one point per game. The real book for Kane’s 2013-14 will be written in the playoffs, where he will reportedly return for Game 1 of the almost-assured Blackhawks/Avalanche first round series.

Patrick Kane’s Career As a Whole

Kane’s career has followed a classic template: athlete introduced to millions of dollars and complete freedom runs wild, makes some mistakes, faces meticulous and often over-the-top scrutinization as a consequence of these mistakes, and eventually matures. A shocking and disturbing number of people in his position follow a more insidious template, allowing their lives to derail into uncontrolled and uninhibited messes and realizing their mistakes only when it is far too late.

Lauding the personal growth of a millionaire athlete who plays his favorite sport for a living may sound odd, but the maturation process is one that every person faces; job, income, and other such factors are irrelevant. Kane was ultimately able to push aside the many distractions and temptations he had and has available to him, and that is something to be respected and admired.

Kane is incontrovertibly brilliant on the ice. Such a characterization has become true of him off the ice as well.

Follow Sean Sarcu on Twitter or add him to your network on Google.

It is not my first time to go to see this web page, i am browsing this web site

dailly and obtain good information from here daily.

It’s going to be end of mine day, except before ending I am reading this impressive article to

improve my knowledge.

Didn’t Kane’s production pick up in during the 2011-12 season when he went to centre for the second time? And then drop off again during the playoffs when he went back to wing?

I don’t have the splits in front of me, but any uptick in production could probably have been attributed to better linemates (Toews out = better wingers left for Kane), an increase in ice time, or something of that ilk. He was clearly less efficient at center, unfortunately; it was a big story that year.

this is old but meh, it still annoyed me.

When Kane was at wing he was playing with Toews, so how exactly did Toews going out mean Kane got better linemates? And Kane was more productive point wise at C the 2nd time than he was at RW, so how is that “clearly less efficient”? It might have been a big story that year, but why not look at the actual data rather than just parrot the narrative? Kane’s production was down that year because of a shit PP, not because he was some awful C. Fancy stat wise he’s been the best 2C for Chicago since 2010, and outside of faceoffs he just spent a year playing 2C in all but name. Kane is bad at C is a meme at this point with no actual evidence to back it up.

Nice job! Kane has always been the most complicated of the Hawks stars. Kudos for talking about Kane’s role in the tying goal in Game 6 vs Boston. No one makes that play but Kane. The whole team deferred to him in starting that rush.

Thanks, James.

Yeah, Bickell deserves his due credit but the play was really Kane’s. Can certainly see why the team hands it to him on the breakout essentially every single time he’s on the ice – just an incredible player in space.