As the Pittsburgh Penguins enter a new NHL season, having five Stanley Cup championships to their credit, being a consistent postseason contender, and boasting current and alumni rosters with names like Mario Lemieux and Sidney Crosby, it’s hard to imagine the city of Pittsburgh as anything less than a hockey town.

However, in 1975, the Pittsburgh hockey scene in general was sparse, and youth hockey programs, especially, were few and far between. Back then, the majority of indoor ice rinks and outdoor frozen ponds catered to recreational and figure skaters. Two rinks were known for their involvement with hockey: the Mt. Lebanon Ice Complex in Mt. Lebanon, Pa, and the Rostraver Ice Garden in Rostraver, Pa.

It was the latter that the mid-70s Penguins franchise, in danger of folding or being sold to another city, turned to during a time of desperation.

History of the Rostraver Ice Garden

The Rostraver Ice Garden, known throughout the area simply as “Rostraver,” opened in 1965 as a 5,000 seat multi-purpose arena with one ice surface, a small stage, an upstairs pub, and not much else.

Over the years, Rostraver has hosted concerts and comedy tours, served as a venue for Extreme Championship Wrestling, been a filming location for the 2008 movie Zack and Miri starring Seth Rogen and Elizabeth Banks, functioned as the home arena for the Pittsburgh RiverRats indoor football team, and home ice and a practice facility for a variety of hockey teams at all skill levels, including the Penguins.

Pittsburgh Penguins bring the NHL to Rostraver

On the ice, the 1974-75 Penguins looked somewhat respectable, finishing in third place in their first season in the Norris Division, and fifth place in the Prince of Wales Conference. They qualified for the playoffs for the third time in their eight seasons in the NHL, ultimately losing the first round in seven games to the New York Islanders after blowing a 3-0 series lead.

Off the ice, the franchise was a mess. Owners Tad Potter and Peter Block couldn’t pay the team’s $6.5 million debt that included $500,000 in federal taxes and were forced to file for bankruptcy on June 13 after the Internal Revenue Service padlocked their offices and seized the club’s assets.

Newspapers had been reporting that the Penguins would be relocated to Seattle following their sale at a bankruptcy auction. However, the purchasing group of Albert Savill, Otto Frenzel, and Wren Blair fought to keep this from happing by purchasing the club for $4.4 million at auction and keeping them in Pittsburgh.

Despite the change in ownership, the club still didn’t have enough money to go around to finance additional expenses, like holding training camp at the Brantford Civic Center in Brantford, Ontario, as they had in the past.

The solution they came up with was simple enough: hold training camp locally, in Pittsburgh, rather than in Canada.

On Aug. 17, 1975, the Pittsburgh Press reported that “for the first time in history,” the Penguins would hold a nine-day training camp in the area, hosting 30 players at Rostraver, 20 miles and a 40-minute drive from their home ice venue, the Civic Arena.

Related – The Ice Rink: A Brief History

Though this decision was made by finances, not of pure choice, the practice of hosting local training camps became a team standard in Pittsburgh that is still the custom today. The Penguins used Rostraver off and on for camp and skills clinics through the 70s and 80s and continued to use other local rinks – like the RMU Island Sports Center on Neville Island, and the IceoPlex at SouthPointe in Cecil Township, Pa. – for practices, camps, and events until the completion of their new practice and training facility, the UPMC Lemieux Sports Complex, located in Cranberry Township, Pa., in 2015.

Rostraver Among the First Rinks in Pittsburgh’s Youth Hockey Scene

Prior to hosting the Penguins in 1975, Rostraver had made a name for itself around the Pittsburgh region. It was one of the few area rinks that provided ice time for youth hockey games and served as a place where lifelong dreams were realized.

Just ask former Philadelphia Flyers goaltender and general manager Ron Hextall.

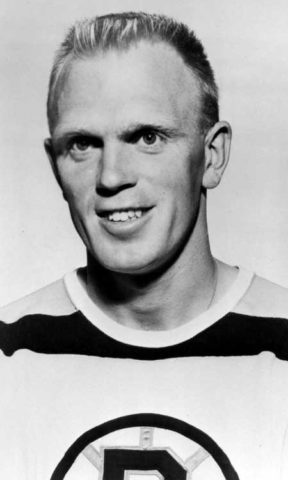

According to a 1989 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article by Chuck Finder, then-eight-year-old Hextall got his first start in net in 1972 at a midget hockey game at Rostraver. He and his family were living in Pittsburgh while his father, Bryan Hextall Jr., was playing for the Penguins.

Ron played forward at the time, as encouraged by his father, but when his team’s goaltender was unable to play that day at Rostraver, Ron stepped between the pipes for the first time, unaware that he would be a Vezina and Conn Smythe Trophy winner, set an NHL record for the most penalty minutes by a goaltender in a single season (113), and be the first goaltender in NHL history to score a goal in the regular season and the playoffs by taking a shot.

Rostraver was among the first rinks in the area to offer these types of experiences to Pittsburgh-area children, though many of them did not go on to have notable careers like Hextall.

When the interest in youth hockey in Pittsburgh began to grow in the 90s with the successful career of Lemieux and the Penguins back-to-back Stanley Cup titles, the lack of available ice still tamped down the town’s dreams of becoming a hockey hotbed.

Penguins Organization Works To Keep Youth Hockey Alive in Pittsburgh

By 1990, more than 100 hockey leagues had been founded in Pittsburgh. High schools that could barely round up enough players for one club team in years past had full varsity and junior varsity rosters. Though the interest was growing, rink development was not.

According to a 1990 Pittsburgh Press article by Scott Newman, there were only 10 functioning rinks within the Pittsburgh region at that time, and only two – Golden Mile rink in Plum, Pa. and Rostraver – were privately funded, without relying on money from the state to stay operational. Without plans to build new rinks, the Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League (WPIAL) and the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association (PIAA) were turning down requests to sanction hockey teams due to costs and lack of venues.

Related: Shattuck-St. Mary’s School – Center of Hockey Excellence

But Penguins head coach Bob Johnson felt that all hope was not lost for the youth hockey scene in Pittsburgh. Johnson was the former head of the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States and had received criticism when the organization wanted to build a second ice rink in Minneapolis, Mn. He told Newman:

They wondered why we needed another [rink in Minneapolis]; they told me that we already had one. But now look at it, they have 60 rinks. Little towns in Minnesota have two rinks. It’s hard to believe. But hopefully, the same thing will happen here, (from ‘Youth hockey growing beyond capacity of rinks,’ Pittsburgh Press – 12/9/90).

Johnson did not live long enough to see the youth hockey system in Pittsburgh grow, and the impact that future Penguins players, the franchise as a whole, and the Pittsburgh Penguins Foundation would have in shaping the culture as we know it today.

As of 2019, youth hockey is thriving in Pittsburgh. There are 62 high school hockey teams registered with the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Hockey League (PIHL); a multitude of peewee and midget leagues, like the Mon Valley Thunder based out of Rostraver, operating in the region; amateur hockey organizations like the Pittsburgh Penguins Elite team that has a list of notable alumni including Brandon Saad, J.T. Miller, Vincent Trocheck, and John Gibson; and a variety of college teams ranging from club level through Division I that host their home games at one of the city’s local rinks.

One player partially responsible for the current hockey boom in Pittsburgh is, of course, Crosby, but not just because youngsters idolize his on-ice performance. His Little Penguins Learn to Play Hockey initiative, founded in 2008, was the first of its kind in the area. The program provides free head-to-toe equipment and low-cost on-ice practices and camps for youth at a variety of rinks across the region, including Rostraver.

Out of this original effort, other programs aimed at bringing hockey to local Pittsburgh children blossomed, like the Learn to Play Dek Hockey program that began in 2017, USA Hockey’s “Try Hockey Free” days that are held in conjunction with Hockey Weekend Across America, and the YMCA Junior Penguins group designed to bring street hockey to city neighborhoods.

The Pittsburgh Penguins Foundation also sponsors a variety of leagues for children of all skills levels and abilities. The Mighty Penguins, Steel City Icebergs, Pittsburgh Inclusion Creates Equality (I.C.E.) and Envision teams were created to allow physically, developmentally, and vision impaired children, as well as those with financial constraints, to experience and enjoy the game of hockey.

The area’s new rinks and programs have allowed the game of hockey to reach many more children, but one piece of Penguins and youth hockey history almost did not make it to the current developmental hockey boom, one of the few that started it all: Rostraver.

Rostraver Is An Example of Pittsburgh Hockey Resilience

On Feb. 14, 2010, following a days-long snowstorm, a 100-by-200 foot section of the roof at Rostraver collapsed during a youth hockey tournament between Canadian and U.S. teams. The sounds of the support beams cracking gave enough notice to evacuate the building and no serious injuries occurred during the incident.

It was all but assumed that the collapse signaled the end of an era, but Rostraver wasn’t going to go down without a fight. After various fundraisers, like bake sales and a car show, and a few generous donations, the old wooden roof was replaced with a new metal structure, and Rostraver reopened on Oct. 21, 2010, just shy of the beginning of most high school hockey seasons.

Seven years later, California University of Pennsylvania junior and hockey team equipment manager Chris Kostick nominated Rostraver for the Kraft Hockeyville USA competition to win $150,000 in arena upgrades. The old barn could no longer stand up to state-of-the-art facilities with multiple ice surfaces, regulated temperature control, and heated locker rooms.

Thanks to fan voting and support from Penguins players like defenseman Ian Cole, Rostraver won the competition, making them eligible for the upgrade money and to host a preseason game between the Penguins and the St. Louis Blues.

While the Zamboni was equipped with laser-cutting technology, and protective netting was added to shield fans from flyaway pucks, the preseason game never materialized. The NHL deemed that Rostraver was “not equipped” to host such a game, but specific reasons why were never given. The game was moved to the UPMC Lemieux Sports Complex, though the Penguins did hold their morning skate at Rostraver on game day, as well as hosting three days of activities at the Ice Garden for fans.

The place that at one time was one of the only hockey-friendly ice rinks in the city and good enough for training camp in the 70s was relegated to a place that needed improvements and wasn’t good enough to host a professional game, albeit a preseason one. Despite the change in its role, Rostraver is a testament to Pittsburgh hockey culture as a whole, its growth, struggle, and resilience. Like Pittsburgh, the old Garden has made its mark on the NHL, and been a place to create memories for countless players throughout the years.