For more than a hundred years, hockey has been a Pennsylvania passion. Its people and teams have made an indelible mark on both the NHL and the sport itself, and fans on both sides of the state have had plenty to cheer, yell, hope, mope, and even cry about. From Hall of Fame classes to shatterproof glass, from Stanley Cups to fisticuffs, the Keystone State has made its mark on the game, and the game has returned the favor.

Pennsylvania Hockey’s Fiery Beginnings

Some of the earliest organized hockey in Pennsylvania was played by collegiate clubs. In the late 1890s, both the University of Pennsylvania and the unrelated Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh) both assembled teams to compete against other colleges and local athletic clubs.

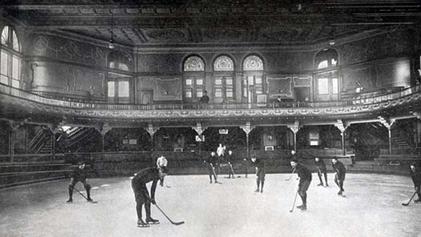

Pittsburgh, at the time, had better infrastructure. The city built the world’s first-ever artificial ice system to create the rink at Schenley Park Casino, which opened in 1895. Less than two years later, however, the system failed, causing an explosion that irreparably damaged the building in December 1897.

That same year, Philadelphia opened its first ice arena. The University of Pennsylvania team had been practicing on ponds and playing games in New York until the West Park Ice Palace opened at 52nd and Jefferson, and briefly hosted the Quaker City Hockey Club. It too met a fiery end, burning down for unknown reasons in 1901.

It would be more than two decades before Philadelphia replaced its first rink but Pittsburgh was well ahead. Just two years after the demise of the Schenley Casino, Duquesne Gardens opened its doors. The fabled building would be home to a number of firsts, not just for Pennsylvania, but for the sport itself.

The NHL’s First Foray into PA

Upon opening, Duquesne Gardens held the world’s largest indoor ice surface, more than 150% the size of a modern NHL rink. It would host countless games, including many from the revolutionary Western Pennsylvania Hockey League, one of the earliest semi-professional hockey organizations. It operated on and off from 1806 until 1909, and was revolutionary in many ways: It was the first league to hire its players and allow them to be traded.

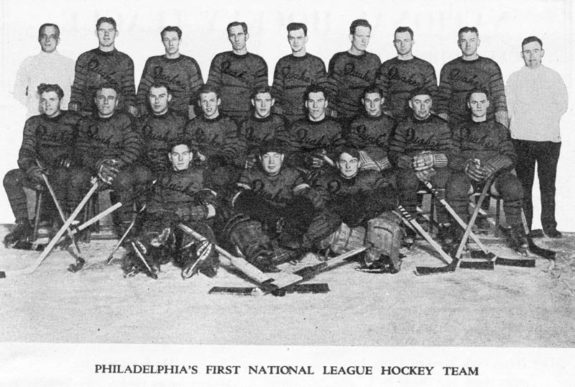

Duquesne Gardens would soon host Pennsylvania’s first ever NHL team. The Pittsburgh Pirates, named for the city’s baseball team, evolved from the Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets of the US Amateur Hockey Association. The Pirates joined the NHL for the 1925-26 season, one of just three American teams out of the seven in the league at the time. The team played five seasons, reaching the playoffs twice.

By 1929, the Pirates had fallen on hard times. They were sold to organized crime boss Bill Dwyer and in their final season, they fatefully switched from Pittsburgh’s recognizable black-and-gold color scheme to an orange and black look…and then packed their bags and headed East to Philadelphia.

The team became the Philadelphia Quakers, playing its lone season in the Philadelphia Arena at 45th and Market Street in West Philadelphia. The Arena had opened in 1920, the city’s first dedicated skating and hockey facility since the fiery demise of the West Park Ice Palace. The Quakers, however, were abysmal. They posted the worst-ever record in NHL history, with just four wins in 44 games (the 1974-75 Washington Capitals would later match that record), and folded a year later.

Both Duquesne Gardens and Philadelphia Arena would host different semi-pro and professional teams from short-lived leagues over the years with the Pittsburgh Hornets of the American Hockey League lasting the longest. For most of their history, they served as the minor league affiliate of the Detroit Red Wings.

The State Waits for the NHL’s Return

In 1940, Pittsburgh Plate Glass developed a form of shatterproof glass, which was eventually installed at Duquesne Gardens–and everywhere else in hockey–after some resistance. It replaced the chicken wire most buildings used above the boards.

Glass changed the way fans viewed the game, and also revolutionized the dynamics of gameplay: Think of how many pucks are cleared off the glass with the sort of predictable trajectory that would be impossible with wire fencing. It also made the referees’ lives easier: One mid-century official recalled that fans used to poke him through the wiring when he’d jump on the dasher to get out of the way.

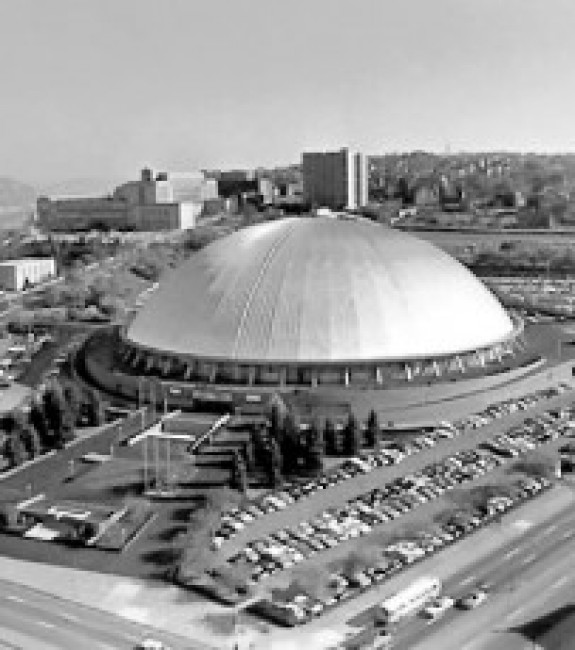

The Hornets inhabited the Gardens from 1936 until 1956, when it was demolished. They would return in 1961 with the construction of the Civic Arena, and that building’s own eventual replacement is named for the paint division of Pittsburgh Plate Glass.

NHL hockey, however, had nearly returned to the state in the 1940s. The once-great Montreal Maroons franchise had been dormant since 1938 due to financial troubles and the second World War. In 1946, Len Peto attempted to buy the rights to the franchise and organize the construction of a 20,000 seat arena (which would have been massive at the time) in Philadelphia.

The new Maroons arena was to be built at the site of the Baker Bowl, one-time home of the Phillies baseball team, which would have indeed placed that NHL franchise on Broad Street–albeit in North Philadelphia. Peto and his group failed to raise the necessary funding by the date set by the NHL, however, and the Maroons franchise folded permanently. The NHL would continue on with just six teams until 1967.

The Penguins and Flyers are Born

When the NHL famously chose to double in size for the 1967-68 season, both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia lined up. Owners from both cities’ beloved NFL teams–themselves once intertwined by the “Steagles” experiment–joined in on early ownership groups. Pittsburgh, with its gleaming new igloo-shaped arena, the Civic Center, and lengthy hockey history, was perhaps an easier choice for the league. Philadelphia was a toss-up, barely beating out a proposal from a Baltimore-based group, but the franchise won out and soon had its own modern arena, the Spectrum.

On Oct. 19, 1967, the Flyers and Penguins played their second games and the first regular season game in Pennsylvania in more than 45 years. In front of less than 8,000 people at the Spectrum, the Flyers skated away with a 1-0 victory. “I think it was the worst hockey game ever played,” Flyers President Bill Putnam said at the time.

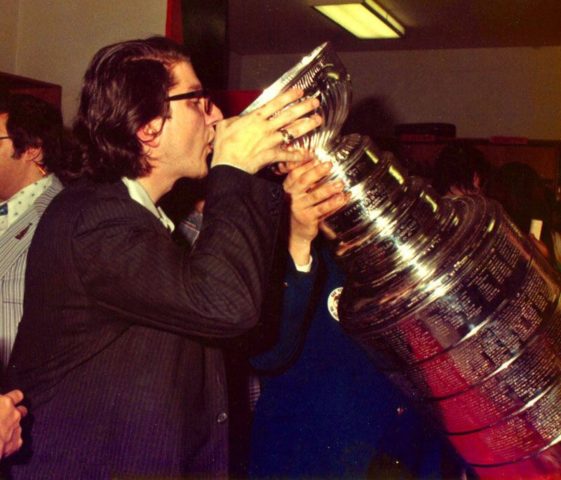

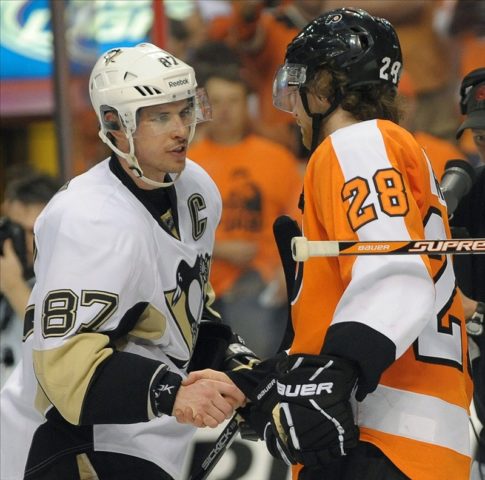

But things were about to get a whole lot better. Both the Flyers and Penguins have experienced soaring highs and crushing lows, with the Flyers winning two Stanley Cups in their first decade of existence, and the Penguins winning five in their last three.

Link: 5 Highlights from 50 Years of Flyers-Penguins Hockey

In the 49 Stanley Cup Finals played since the 1967 expansion, the two teams have combined for 14 appearances. No other state or province has been represented in the final round that many times, meaning Pennsylvanians have perhaps had more of a rooting interest than anyone else over the years: either cheering for their favorite team to win a Cup or praying that their bitter rival does not.

The NHL in PA: Two Success Stories

Fifty-two years later since the birth of its two NHL teams, and more than a century of organized play, it’s hard to call hockey in Pennsylvania anything but a resounding success.

Both fanbases have plenty to be proud of. The history of the Flyers has been one of remarkable consistency: They were the first non-Original Six team to reach 2,000 wins, though they’ve won just two of the eight championship rounds they’ve reached. They were the first non-Original Six team to win a Stanley Cup since the Montreal Maroons franchise that very nearly beat them to town, and they did so while redefining the sport’s relationship with violence.

The Penguins’ history has had high peaks and low valleys. The franchise has run into financial difficulties, twice flirting with or declaring bankruptcy, but those troubles are now a distant memory. The Western Pennsylvania group has had the good fortune to draft two of the greatest hockey players to ever live and assemble five terrific championship-winning squads around them.

Off-ice heartache has struck both franchises. In 1971, promising young Penguin Michel Brière was killed in a car accident after his rookie season, snuffing out a young life and potentially stunting the franchise’s path to prominence. Fourteen years later, the world lost young Flyers goaltender Pelle Lindbergh to the same fate. Neither Lindbergh’s #31 nor Brière’s #21 has been worn by a member of their franchise since.

Between the two organizations, there have been 24 Hall of Fame players and 10 builders, almost equally split. Two of them played for both teams: Paul Coffey and Mark Recchi. A third, Jaromir Jagr, will enter the Hall the second he formally retires.

When one of those greats, Mario Lemieux, returned to the ice after missing time for cancer treatment, he came back to a raucous Spectrum crowd in Philadelphia, one that greeted him with a standing ovation.

Pennsylvania Hockey Now and Beyond

Hockey is thriving in Pennsylvania, and not just at the professional level. Both the Flyers and Penguins have their AHL affiliates in the state, as do the Washington Capitals. Several college teams, an ECHL squad, and even Connor McDavid’s former OHL club play here.

Innovations are still occurring, too: Just recently, the same company that developed hockey glass, PPG, helped the NHL develop its first thermochromic pucks, whose paint changes color to reflect temperature.

To date, 36 Pennsylvanians have played at least one NHL game–most of them from the Pittsburgh area, though perhaps the most notable, former New York Rangers goalie Mike Richter, grew up outside of Philadelphia. Four Pittsburghers are active in the league: Vincent Trochek, John Gibson, Brandon Saad, and Matt Bartkowski. A number of others, like Ohio-born JT Miller and New Jersey-bred Johnny Gaudreau, grew up right across state lines rooting for their local PA team.

But that number will likely grow fast. Today, the state has over 32,000 registered amateur players, according to USA Hockey. That’s the sixth-most in the United States. And there are more than 300 active high school teams, more than any other state.

It’s also working to diversify the sport. Late Flyers chairman Ed Snider created and endowed a program, Snider Hockey, that combines academic mentorship with hockey programs, providing children in Philadelphia, who might not otherwise know the sport, with equipment and ice time, and it’s already iced dozens of teams and reached thousands of children. Pennsylvania’s USA Hockey membership also includes over 3,000 female players, another top-10 number nationwide.

Fittingly, Pennsylvania is also the only state that USA Hockey divides across two different counting regions: the eastern side is looped in with New Jersey and Delaware, while the western side is counted along with Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia, and Indiana. Philadelphia’s a huge, gritty Eastern seaboard city, separated by a mountain range from Pittsburgh’s more colloquial, near-midwestern flair. The two can’t even agree on whether it’s called “soda” or “pop” and most citizens of one have a passionate disdain for the other’s hockey team.

But fans across the state have plenty to be proud of, and even more to look forward to. Today, they get to enjoy the greatness of at least three more future Hall of Fame members in Evgeni Malkin, Sidney Crosby, and yes, Claude Giroux (it’s hard to imagine Kris Letang not getting the call, either). The Penguins’ Cup contention window is far from closed, and with a budding core of young talent, the Flyers’ will soon open.

Now, 124 years since the world’s first indoor artificial ice rink opened here, the state’s two storied NHL teams will take their rivalry outside again. Despite the novel setting, the 2019 Stadium Series game will likely resemble the previous 287 meetings: brightly-colored, often heated, always entertaining, and a great way to spend a few hours on a Saturday night in the Keystone State.

Enjoy more great hockey history and ‘Best of’ posts in the THW Archives