Phil Esposito hung up his skates for good 40 years ago today. On Jan. 9, 1981, he played his 1,282nd and final NHL game, earning an assist in the New York Rangers’ 3-3 tie with the Buffalo Sabres at Madison Square Garden.

The fact that Espo was wearing a Rangers sweater that night was remarkable in itself. Six years earlier, he’d gotten the shock of his life when the Boston Bruins, the team he helped carry to two Stanley Cup championships with offensive numbers the likes of which no one had ever seen, traded him. Not only did the Bruins send him away, but they also sent him to their most-hated rival, the Rangers.

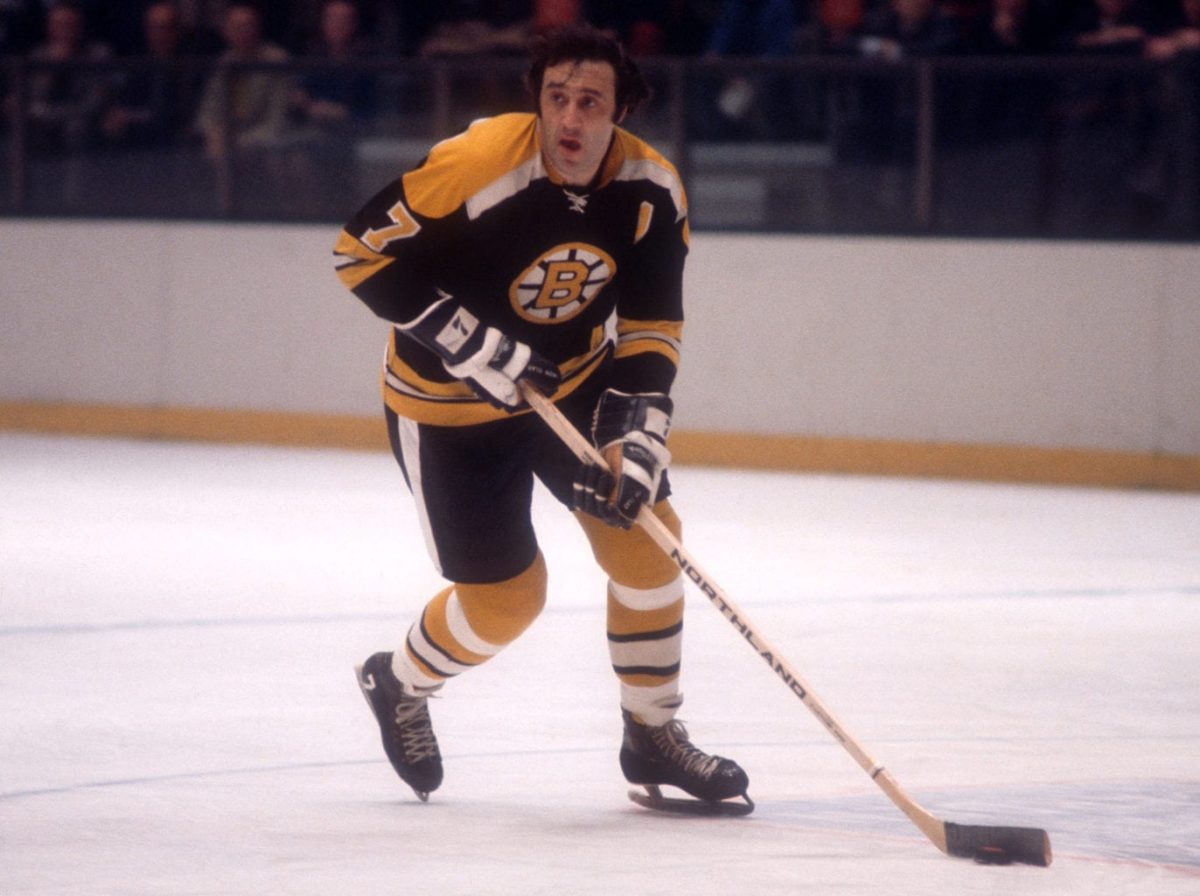

Esposito was hated in New York — the kind of player hatred that’s almost never seen today, and the rare player that even normally level-headed fans would curse at. He was a big man for his era (the NHL lists him as 6-foot-1, 205 pounds, but he looked and played bigger) in a league where the average player was about 5-foot-11, 190 pounds.

His straightaway speed was nothing special, but his quickness, strength and hands around the net were remarkable, and combined with his size and quick release (he popularized what we know today as the snapshot), Esposito made life miserable for opposing goalies to a degree unseen before him.

“I just plod along, nice and slow,” he once said, “though I get my goals.”

Mutual Dislike

The antipathy between Esposito and New York was mutual. He hated the city, hated the Rangers, hated Madison Square Garden and the area around it. One of his happiest moments in hockey was beating the Rangers in Game 6 of the 1972 Stanley Cup Final at the Garden, giving Boston its second championship in three seasons.

Esposito was 33 in the fall of 1975 and had recently signed a four-year contract worth $200,000 a season (huge money in the mid-1970s). He was coming off five consecutive seasons that saw him score at least 55 goals and 127 points, and he’d put up six goals and 16 points in Boston’s first 12 games of the 1975-76 season.

But the Bruins and Rangers were coming off respective Preliminary Round losses in the 1975 Stanley Cup Playoffs, and neither was off to a good start; Boston was just 5-5-2 in its first 12 games, and the Rangers were 5-7-1 in their first 13, their worst start in more than a decade.

The Rangers had already traded one veteran goalie (Gilles Villemure, to the Chicago Black Hawks), seen another claimed on waivers (Ed Giacomin, by the Detroit Red Wings) and looked like a team that was starting a teardown. Instead, they turned to their biggest rival during the previous decade and made a trade that seemed almost incomprehensible: Esposito and defenseman Carol Vadnais for center Jean Ratelle, defenseman Brad Park and minor league defenseman Joe Zanussi.

‘Please Don’t Say it’s New York’

Esposito was in Vancouver preparing for a game against the Canucks on Nov. 7, 1975, when coach Don Cherry came to his hotel room to tell him the team had traded him.

“I said, ‘Please don’t say it’s New York, please, because if you do I am going to jump out the window,” Espo told Cherry, whose lunch-pail ethic didn’t mesh with his now-former center’s approach. “He says, ‘Close the window!’

“Of all the places I didn’t want to be was New York.”

To say the trade came as a shock to Esposito would be an understatement. He had come to love Boston after being traded to the Bruins by Chicago in May 1967 and wanted no part of leaving.

“I loved Boston and I loved the Bruins,” he recalled years later. “We were really a team. We played hard and we hung out together and we won Stanley Cups together. I think if I had stayed we would have won a couple more. The last place I wanted to be traded to was the Rangers because they were our enemies.”

Those enemies quickly became friends. Esposito hopped a plane to Oakland and, wearing No. 5 instead of his customary No. 7 (which belonged to Rangers icon Rod Gilbert), scored two goals and assisted on another in a 7-5 loss to the lowly Golden Seals. He was scoreless the next night in a 3-1 loss to the Kings in Los Angeles, missed a week with a knee injury, then returned and began putting up points — though not the way he had in Boston.

Esposito finished 1975-76 with 29 goals and 67 points (and a minus-38 rating) in 62 games for the Rangers, who missed the Stanley Cup Playoffs for the first time in a decade. They missed again in 1976-77 despite Esposito’s 80 points (34 goals, 46 assists) in 80 games — numbers that in the high-scoring 1970s were only enough to tie him for 17th in the NHL in scoring.

His 81 points (38 goals, 43 assists) in 1977-78 were good for 15th in the scoring race and helped New York get back to the playoffs, though they lost their Preliminary Round series to Buffalo in the third and deciding game.

Meanwhile, the revamped Bruins remained among the NHL’s elite teams. They reached the Semifinals in 1976 and lost the Stanley Cup Final to the Montreal Canadiens in 1977 and 1978.

Turning Boos to Cheers

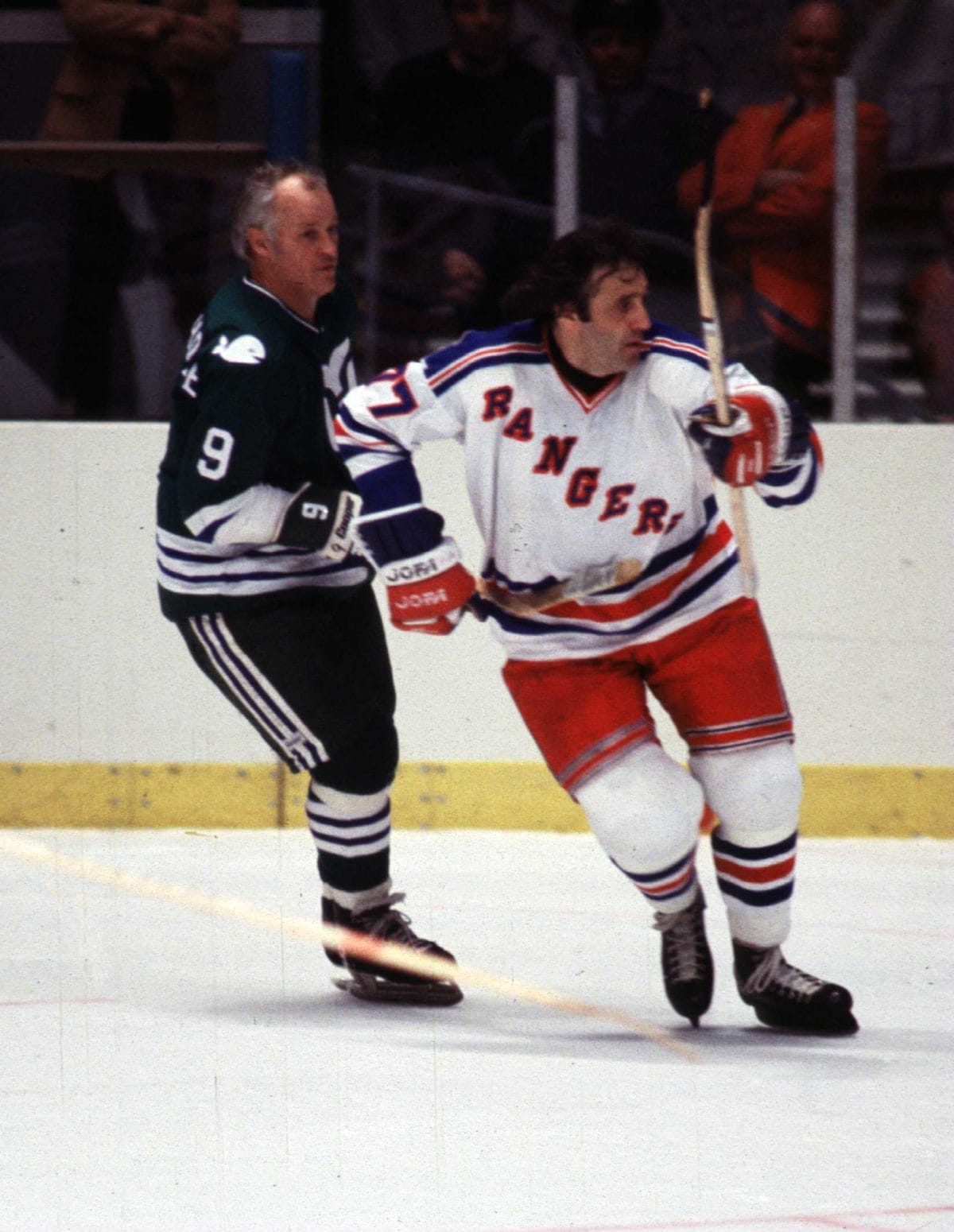

But a funny thing was happening to Esposito. New York, the city he couldn’t stand, had become home — and Rangers fans, who had loathed him, now cheered him as if he’d played his whole career in the Big Apple.

“All I knew about New York was between Seventh and Eighth avenues and 33rd and 34th streets, Madison Square Garden,” he once said. “When I did learn the city, it was … the greatest city and the greatest fans. We had some good years.”

Those cheers got even louder in 1978-79, when Esposito, centering for young wings Don Maloney and Don Murdoch, scored 42 goals, the most he would score as a Ranger. His line, dubbed “The Godfather and Two Dons,” helped the Rangers upset the regular-season champion New York Islanders in the Semifinals before losing to Montreal in a five-game Final.

Esposito and the Rangers made it to the Quarterfinals the following year, but by Christmas of 1980, he knew the end was near. After averaging more than a point-per-game in his first five seasons with the Rangers, he was putting up less than half that in 1980-81. He was 38 and looked every day of it. New coach Craig Patrick wanted to go with youth and speed; Espo had neither.

Saying Goodbye

His final point was the primary assist on a first-period goal by Dean Talafous in his last game. He nearly scored in the final seconds, but Sabres defenseman Mike Ramsay got a glove on his wide-open shot from the slot.

Esposito was the most prolific active player in the NHL when he retired; his 717 goals were exceeded only by the 801 scored by Gordie Howe (who played 485 more games) and are still sixth all-time. Esposito’s 873 assists gave him 1,590 points, second to Howe’s 1,049 and 1,850 at that time. He retired having won the Hart Trophy as MVP twice and the Art Ross Trophy as scoring leader five times.

There was no Maurice Richard Trophy given to the top goal-scorer in the league; if there had been, he’d have won six in a row, from 1968-69 through 1974-75.

His post-playing career has lasted more than twice as long as his time as a player and includes stints as a coach, general manager and broadcaster with the Rangers, as well as establishing and running the Tampa Bay Lightning (he’s still a broadcaster for the defending Stanley Cup champs).

That’s all well and good. But on the 40th anniversary of his retirement, don’t forget that Esposito was the most feared scorer of his era, a player who was a threat every time the puck was on his stick and set single-season records that it took Wayne Gretzky to break.