What comes to mind when you hear the words “black and gold?” Most people will probably answer with either the Penguins, Pirates, Steelers, or even the Wiz Khalifa song “Black and Yellow.”

These colors have become synonymous with the sports teams that make up the “City of Champions”, but in January 1980, the Boston Bruins tried to put a stop to the Penguins’ use of the black and gold color scheme. The result was one of the sillier feuds in NHL history.

The Penguins’ Road to Black & Gold

In their inaugural season, 1967-68, the Penguins donnedpowder blue and white jerseys with the word “Pittsburgh” written diagonally across the front. The design was far from original, given that the New York Rangers had been wearing it since 1926. The color scheme, too, was nothing creative. At the time, six of the 12 teams in the NHL used blue as a primary or secondary team color.

Though the Penguins’ emblem changed throughout the years – evolving from lettering, to a circular logo with a Penguin inside, to the skating Penguin still used today – the blue and white color scheme remained the same for the first 12-and-a-half seasons, changing it up only by adding a darker navy blue to the mix.

By the 1979-80 season, the Penguins were ready for an even bigger change. Hoping to light a spark under a franchise that went through bankruptcy and barely staved off relocation to Seattle just four seasons earlier, management felt that tying the team to something greater than themselves would raise fan interest and push the players to perform at a higher caliber.

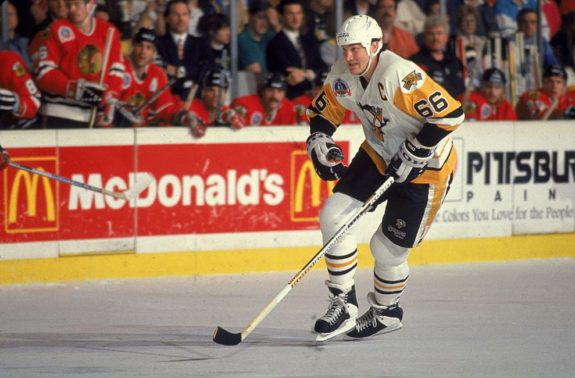

The solution was to change the team’s colors from blue and white to black and gold, to align it with the 1979 Super Bowl Champion Pittsburgh Steelers, who adopted the color scheme from their founding in 1933, and the 1979 World Series Champion Pittsburgh Pirates, who adopted it in 1948. Associating the Penguins with the city’s other powerhouse franchises could only do them good in the eyes of the public.

Boston Bruins management had other ideas.

The Bruins Push Back

Before the Penguins took the ice at the Civic Arena against the Montreal Canadiens on Jan. 2, 1980, a rumor circulated through the press box: the Penguins were going to adopt black and gold uniforms for the remainder of the season and beyond.

Wanting to find out if there was any truth to that bit of gossip, Pittsburgh Press reporter Bob Black investigated after the game, sniffing around the locker room for clues of what was to come. In his Jan. 3 article, “Pens’ Win Over Montreal Changes Color of Division,” Black said that “there is no truth to the rumor that the Penguins will change to black and gold uniforms,” even going so far as to ask Penguins right winger Pat Hughes what he thought of the idea. Hughes said:

I think we proved tonight that something like [changing our uniforms] isn’t necessary. I don’t think the color of our uniforms would impress Montreal at all,”

(from ‘Pens’ Win Over Montreal Changes Color of Division,’ Pittsburgh Press – 1/3/80).

However, just eight days later, Penguins vice president, Paul Martha was singing a different tune. He told the Pittsburgh Press’ Dan Donovan:

A change to black and gold is in our plans. Exactly when it is yet to be determined, but it will be this year. Black and gold has become Pittsburgh. And the Penguins are Pittsburgh. I think it’s a simple equation and a decision that’s easy to make,”

(from ‘Pens Will Wear Black and Gold,’ Pittsburgh Press – 1/11/80).

By this time, 10 of the 21 NHL teams used blue as a basic color for their road jerseys, and both the Bruins and Vancouver Canucks used yellow or gold striping or trim on their sweaters, meaning the Penguins uniforms would become more unique with the new scheme.

When asked about the Bruins’ opinion of the switch, Martha said the Massachusetts club was not opposed to what the Penguins had in mind, “not vehemently anyway,” he added at the end of the interview.

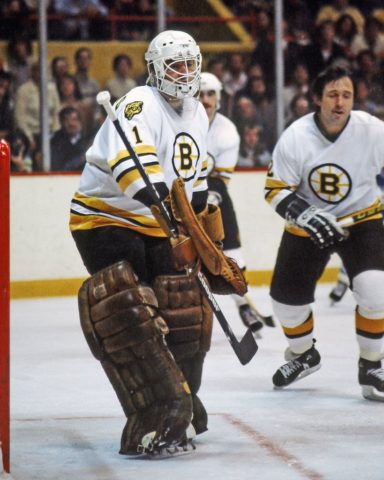

Martha must have had a different definition of the word “vehemently” than the rest of the world because Bruins general manager, Harry Sinden and team president, Paul Mooney were anything but relaxed about the Penguins’ decision.

In an interview with Will McDonough of the Boston Globe, Sinden said:

There’s no way we’re giving permission for them to adopt our colors. Those colors are part of our tradition and heritage. We’re going to fight it if Pittsburgh tries to do it,”

(from ‘Eck [as in wreck] joins the list,’ Boston Globe – 1/24/80).

Mooney, more tactfully, stated the when the Penguins were admitted to the league in 1967, they had to declare their team colors and chose blue and white. He felt that the Penguins had been trying to encroach on their territory for some time, as they added black and gold to their skating Penguin logo over the years. In the same Boston Globe article, Mooney said:

I sent a telegram to our league president (John Ziegler), telling him we feel we have exclusive rights to those colors in our league and we were not going to give the Penguins permission to change.”

If it sounds a bit petty of the Bruins organization to insist that they had exclusive rights to a color scheme in a league where half the teams were wearing similar blue uniforms without complaint, that’s because it was. Martha even went on record saying he found the protest “a little silly.”

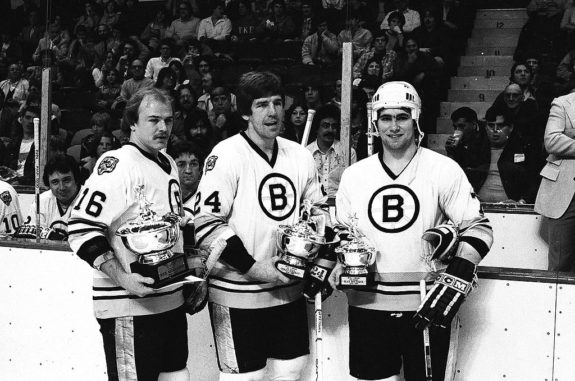

Perhaps Boston blew the color scheme issue out of proportion due to their already strained ties with league president Ziegler following a Dec. 23, 1979 incident in which all but one Bruins player climbed over the glass after a 4-3 win against the Rangers at Madison Square Garden and engaged in a brawl with fans that would become infamously known as “The Shoe Incident.”

Three Bruins – Terry O’Reilly, Peter McNab, and Mike Milbury – were suspended for eight, six, and six games, respectively, and each fined $500. The incident also resulted in lawsuits and the installation of higher glass throughout NHL arenas. Members of the Bruins organization, as well as reporters from the Boston Globe, like Francis Rosa, felt the punishments were too harsh and did not fit the crime.

For the second time in two months, Ziegler did something to displease the Bruins. He did not find that the Penguins needed their permission to change uniform colors, and okayed the movement.

Either a coincidence or perhaps as an extra zinger to Boston’s already enraged camp, the Penguins planned to debut their new black and gold outfits in a back-to-back series against the Bruins in late January 1980. However, due to manufacturing issues, the new sweaters were not ready until Jan. 30 and were worn for the first time in a 4-3 loss to the St. Louis Blues at the Civic Arena.

The (Other) Pittsburgh Pirates Save the Day

Though the Bruins’ main protest was that they had had exclusive use of the black and gold color scheme for 50 years in the NHL, they weren’t, in fact, the first team in the league to use that palate.

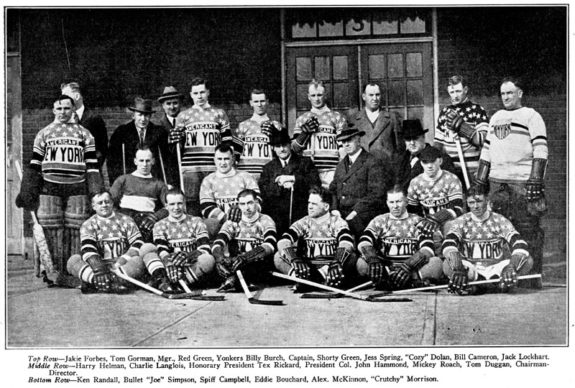

In 1925, the Pittsburgh Pirates became the third team the NHL’s American Division, joining the New York Americans and the Bruins.

An evolution from the Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets, an amateur and semi-pro team that played from 1915-25, the Pirates took their name from the city’s baseball team but were the first Pittsburgh sports team, as well as the first NHL team, to wear black and gold. At the time, the Bruins wore gold and brown to reflect the colors of owner Charles Adams’ grocery store chain, First National Stores.

The hockey Pirates chose black and gold for their colors not only to pay homage to Pittsburgh’s city flag but also thanks to some unusual donations from the Pittsburgh Police Department. Attorney James Callahan, the Pirates owner, had a brother who worked for the Pittsburgh Police who gave Callahan some old emblems, seals, and patches to use as logos for their new uniforms, all of which were in the city’s signature colors: black and gold.

The Pittsburgh Hornets, a minor-league team from the city also wore black and gold from 1951-53, before becoming an American Hockey League (AHL) affiliate for the Detroit Red Wings for the second time, and changing back to red and white uniforms to align with their NHL club.

Martha cited the Pirates existence as Pittsburgh’s first NHL club, and their use of the black and gold color scheme to ultimately disprove Boston’s theory of their “exclusive rights.” Without these hockey Pirates, the Penguins could have been stuck wearing the blue jerseys of doom forever.

As of 2019, 15 out of 31 teams use black in their color scheme, and 11 use a shade of gold or yellow in their palate. Seven teams in total use both black and gold on their uniforms, including the Penguins, Bruins, Ottawa Senators, Anaheim Ducks, Calgary Flames, and Vegas Golden Knights.

During the 2021-22 season another team could start to call themselves the black and gold. Ownership forSeattle’s expansion team has yet to pick a name or a color scheme for the new franchise. Could another color war surface in the NHL in the near future? We’ll just have to wait and see.