It takes a team effort to win in the playoffs. 12 forwards, 6 defensemen, and 2 goalies. Coaches often have to turn to even more players than that.

“Penalty kill, power play, guys are doing a lot of different things that lead to success on this team,” Jarome Iginla said recently of the Pittsburgh Penguins. “When I got here, I noticed right away that everybody enjoys their different roles and takes pride in them. That’s easier said than done sometimes.”

Especially for the less than glamorous jobs. No one remembers the critical blocked shot or the relentless forecheck that burned 40 seconds off the clock unless it salvages a win.

Penalty killing might be the most thankless of those jobs. Your team has taken a penalty and now it’s up to you and three of your teammates to minimize the damage as much as possible. A ten percent failure rate is considered elite, yet 20 percent failure is downright awful. Either way, everyone remembers when the penalty kill falters.

__________________________________

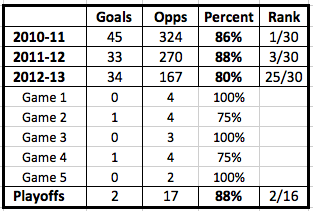

Penalty killing has typically been the strong suit for the Pittsburgh Penguins. They led the league in 2010-11 at 86 percent and finished third the following year despite an improvement to 88 percent.

Penalty killing has typically been the strong suit for the Pittsburgh Penguins. They led the league in 2010-11 at 86 percent and finished third the following year despite an improvement to 88 percent.

But in both years the Penguins PK unit collapsed in the playoffs and was blamed heavily for first-round losses to Tampa Bay (70%) and Philadelphia (48%).

This year, the unit struggled throughout the regular season, (killing at only 80 percent, 25th in the league), but has been an underrated strength for the Penguins so far in their matchup with the Islanders (88%).

So what do all of these numbers mean? Why the Jekyll and Hyde act?

Assistant coach Tony Granato has directed the penalty kill for years and the system rarely varies from night to night. Even the personnel — Craig Adams, Pascal Dupuis, Matt Cooke up front; Brooks Orpik, Paul Martin, Kris Letang on defense — is pretty much the same as its always been. The Penguins lost penalty killers Jordan Staal and Zbynek Michalek in the offseason, but both players were big reasons the PK unit failed in prior playoff campaigns.

One explanation is goaltending.

The old adage is that a goaltender is your most important penalty killer. Earlier this year, THW’s Billy Nauman pointed out that Tomas Vokoun’s save percentage on the penalty kill was nothing short of abysmal:

[Vokoun’s] .781 shorthanded save percentage is strikingly lower than his average performance over the last four years. And even last year Vokoun had a .869 save percentage shorthanded.

…The Penguins are also being vastly outshot shorthanded with Vokoun in net compared to Fleury. On a per-60-minute basis, the Penguins are allowing seven more shots against on average with Vokoun than they are with Fleury.

If the Penguins are truly less confident with Vokoun, it would seem reasonable that they would clamp down in this scenario. They’re not pushing to score shorthanded. It could be that Vokoun’s rebounds are inflating the total, since every time he fails the freeze the puck he creates more work for himself.

But no matter what the reason, it doesn’t immediately explain why Vokoun is saving so few of the shots against him shorthanded.

So maybe it was just bad luck? A few weak goals can lead to a lack of confidence for the whole unit and it collapses on itself from there.

In order to analyze, it probably makes sense to figure out what the Penguins are actually trying to do on the penalty kill. Then we’ll be able to notice when the wheels are starting to fall off or another team has gameplanned an effective way to capitalize on their powerplay opportunities.

The Forecheck

Let’s first start with the forecheck.

Let’s first start with the forecheck.

15 or 20 times a game we see the puck sent down the ice and a defenseman on the powerplay stops behind his net. His team starts a set breakout play and they move back the other way as a unit.

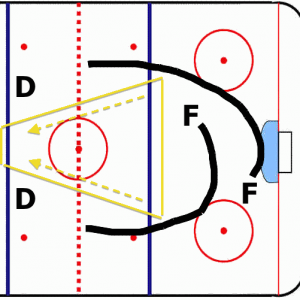

Against most teams (including the Islanders), the Penguins’ two forwards swing into position. One forward lightly pressures in front of the net and then usually locks onto a winger heading up one side of the ice. The other forward swings the other way and does the same.

If the opportunity to pick off a pass presents itself, the forwards will jump on it, but they’re usually just looking to disrupt the rhythm and timing of the set breakout.

As the puck moves into the neutral zone, the Penguins start to force the Islanders into certain spots. Ideally, they force a player onto his backhand and take away any easy passing options. Sometimes they funnel the player with the puck to the middle of the ice and challenge him to make a play at the blueline.

Either way, the goal is to force a turnover or a dump.

The First Eight Seconds

Teams on the powerplay anticipate a scenario where they’ll be forced to dump the puck and are smart about where they send it.

Maybe it makes sense to chip it softly into Douglas Murray’s corner and beat him in a race to the puck? Or rip it around the glass and force a weak puck-handling goalie like Marc-Andre Fleury out of the net? Every team has a different strategy.

The Penguins obviously hope to gather the dump as quickly as possible and send it back down the ice.

But if the Islanders are successful, the Penguins won’t be able to clear it cleanly. In this case, the Penguins go into all-out-attack mode.

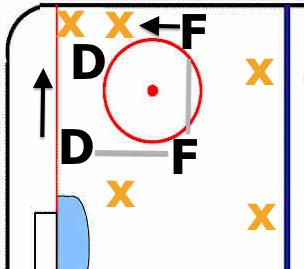

The Penguins send two and sometimes three players after the puck in the corner. They check, punch, slash and do anything they can to keep the Islanders from setting up their powerplay.

At every level of hockey, players on the powerplay are told to outnumber the other team on the puck. But look at the diagram to the right. The Penguins’ aggressive penalty kill allows them to be the one with the numbers advantage.

Even if all three Islanders forwards go into the corner, Pittsburgh still has them outnumbered in that area of the ice. You’ll rarely see a defenseman on the powerplay skate into the corner to join a 3-on-3 battle.

For years, Penguins penalty killers have preached the importance of the ‘first eight seconds’. Their philosophy is that after the initial dump they have eight seconds to force a turnover and clear the puck down the ice. If they can’t get a clear in that time, there’s a good chance the other team will be able to move the puck and take advantage of their over-aggressiveness.

With that in mind, the smart powerplay teams are the ones that move the puck from low to high as quickly as possible.

The Islanders almost always pick up the dump and get it back to Mark Streit on the point right away. This forces the Penguins out of the eight-second attack mode and into a normal penalty kill rotation where New York has the numbers advantage.

Pittsburgh’s in-zone rotation varies too much by opponent and situation to diagram. In short, the Penguins penalty killers rely on intense video analysis — even in between periods on team laptops and iPads — to scout tendencies and anticipate set plays.

It becomes a chess match. The Islanders try to create scoring opportunities, while the Penguins take away shooting lanes and try to steer the puck back into the corner.

Look at the angle Craig Adams is taking when challenging John Tavares at the bottom of the screen:

Tavares isn’t going to try a risky pass back to the defenseman over Adams’ stick. He’s going to take the ice Adams gives him and attack the net.

The Penguins will then force him to pass the puck down into the corner — the least threatening area of the ice on the powerplay. New York will probably have a numbers advantage, but a Penguins defenseman will go into a full-body slide and take away any potential pass in front:

New York will be forced to regroup and attack in a different way.

Over and over again.

The Islanders want to move the puck quick and confuse the Penguins as they rotate in coverage.

The Penguins will still be taking away shooting lanes and forcing the puck into the corner. In any situation where the puck is bouncing/loose, or an Islanders player has his back turned, Pittsburgh will jump into attack mode again.

Punch, slash, pokecheck, and hopefully a clear.

Here’s two video examples of the Penguins in attack mode in the corner against the Islanders to further illustrate the point:

__________________________________________

Now we’ve seen what the Penguins penalty kill looks like when it’s effective. What about the other 34 times this year when teams have scored on the powerplay?

When the Islanders had powerplay success in an early season matchup with Pittsburgh, they passed the puck quickly from side to side:

“It was great movement,” Tavares told CBS Sports’ Adam Gretz. “We were feeling the pressure they were putting on us and recognizing the open guy, and I was lucky enough to do the easy part.”

Brandon Sutter tries to steer the Islanders into the corner, but it’s no use when a team moves the puck that quickly and has one extra player on the ice. The Islanders will need more powerplay goals like the one above if they’re going to stay alive in their series with the Penguins.

Eight seconds doesn’t seem like a long time, but for a Penguins penalty killer it can mean the difference between unnoticed success and obvious failure.

___________________________________________

Why the Pens are doing better now. They have a 250 lb bruiser who clears the crease. Murray is the Hal Gill of 2013.

The fact that Paul Martin doesn’t have his stick on the ice either time the puck was sent down low certainly doesn’t help..