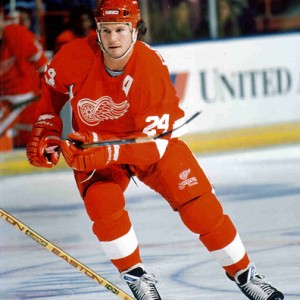

Yesterday marked the 19th anniversary of Bob Probert’s retirement from the NHL. Tragically, on July 5 of this wretched year, it is now 11 years since the giant of a man suddenly passed. As such, this is my tribute to a near mythical being gone far too soon.

Meeting my Hero

At age 16, I was playing Midget AAA in my hometown of Lethbridge, Alberta. In Jan. 1993 I was invited by a friend and his family to join them on the two-hour drive north to watch the Detroit Red Wings play the Calgary Flames in the infamous Saddledome. Honestly, I could not tell you the final score, but will never forget the fact that my hero had two good “dust ups” with current St. Louis Blues coach, Craig Berube. Most importantly, this would also be the first and last time meeting Mr. Probert.

I cannot recall all of the specific details, but we had the “connections” to get downstairs so we could meet some of the Red Wings players. My good friend (who was incidentally later drafted by the Quebec Nordiques of all teams) stood by and smartly collected autographs from players like Steve Yzerman, a very young Sergei Fedorov and Nicklas Lidstrom, as well as Russian legend Vladimir Konstantinov. I on the other hand, only wanted to wait for Mr. Probert and shake his hand.

He was one of the last players to exit the dressing room that evening and as he sauntered out of the room in his long leather trench coat, I managed to squeak out: “good game Mr. Probert.” He shook my hand, said “thanks kid,” and then walked out to the bus. That was it. However, as brief an encounter as it was, that moment is forever etched in my memory.

Legend Status

In the years after that day in 1993, Probert’s legend only grew larger. He had an aura that appealed to a generation wrapped up in a misled identity of being tough. Today, he would now be considered a shocking candidate for a role model. But that was also a big part of it.

Our generation grew up on Rock ’em Sock ’em videos that were in our stockings each holiday season. That rugged style of play was the norm and Probert embodied everything a lot of young men wanted to be like during that period of hockey history — widely respected, brutally honest, humble, powerful, talented, and more than a bit wild.

Troubles and CTE

As the legend of Probert grew larger on the ice it began to spill over off the ice and into his personal life. Documenting the specifics would be futile at this point but suffice to say there were numerous legal matters and a definitive pattern of substance abuse. While people were heavily judgmental back then, and likely still are, we are now acutely aware of what this larger-than-life figure may have been experiencing.

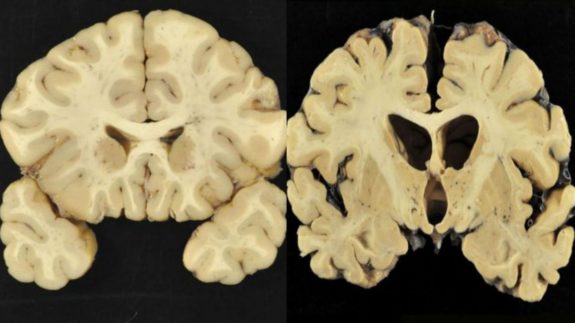

Posthumously, doctors at Boston University discovered Probert’s brain had brain bruises. More specifically, his brain had signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy or what is now commonly referred to as CTE. The effects of CTE can be both detrimental and degenerative over time. Eventually, the degeneration can lead to behavioral changes and/or anxiety/depressive symptoms. As a result, many victims of brain injury turn to self-medication as a means of coping.

The effects of CTE are now well known, but back then it was simply shaking off the cobwebs after you got your bell rung.

Changes in the Game

With more information and research about brain trauma, the game of hockey has altered its stance on “physical” play. More accurately, the game has slowly fazed out fighting and any notion of an enforcer role. As such, the game of hockey is now played much differently, especially in terms of fighting, intimidation, protection, etc. That element in the game now pales in comparison to how it was several decades ago.

Candidly, it took me a long time to bend my resistance toward the softening of the game. I was “old school” and believed that those were the good old days — that is how the game should be played. That change in belief has been gradual since the summer of 2011.

Within a five-month period in 2011, three former NHL “enforcers” passed away. All three players — Derek Boogaard, Rick Rypien, and Wade Belak — were known as tough Western Canadian kids that had no problem handling themselves. (from ‘Hockey Players’ Deaths Pose a Tragic Riddle,’ New York Times, 09/01/2011) However, they all may have also been experiencing similar effects as a result of brain injury(ies). It was devastating. Those three incidents, along with the passing of Probert (and many others since that time as noted in tweet above) and my own personal struggles has gradually changed my thinking about the changes within the game.

Do I miss fighting in the game? Absolutely. That brief moment when two “heavies” squared off is tough to beat in terms of pure entertainment, anticipation, and excitement. However, given the obvious correlation between head trauma and a variety of health issues, I have come to the conclusion that the move away from fighting could be saving this current generation from unnecessary long-term grief.

The Measuring Stick

Probert will always be remembered as the “measuring stick,” as Tony Twist once eloquently stated. If you were the “measuring stick” then you were the toughest kid on the block. Probert put himself on the line every night and had little to no regard for his own safety.

Judge him all you want, but it is almost unfathomable what he must have been thinking and feeling as he had to defend his “title” every night, season after season. Most folks looking down on his situation have likely never even felt the physiological response from a physical confrontation, let alone do it night after night in front of 20,000 fans.

Always Remembered

A collectors piece that has become a staple in my home is a signed Probert – #24 – Red Wings jersey. It is a small homage to the man that will always be my favorite NHL player of all time. To me, he is the Last King from an era of hockey that is now merely history.

While Probert will always be remembered fondly by his enormous fan base, I cannot imagine how much his immediate family must still miss him a decade later. Probert is survived by his wife Dani, and their four children — daughters Brogan and Declyn as well as the twins, Jack and Tierney.

Since 2011, Dani and the family have raised over $1.2 million hosting the annual Bob Probert Motorcycle Ride, which raises funds for cardiac care in the Windsor-Essex area. For those interested, you can visit the home page by clicking here.