As a Calder Trophy finalist defenseman, who averaged nearly 24 minutes per night while being deployed in tough situations more often than not, one might assume that Owen Power was an effective player in his own zone. In fact, Buffalo Sabres coach Don Granato said just last month that Power’s defensive awareness was on par with players much more seasoned than himself.

However, analytical models disagree with this take — Power’s defensive impacts are among the worst on the team, and are generally much worse than most Sabres players, even his defensive partners. Though statistics almost always tell the full story of a player’s effectiveness on the ice, is that the case for Power?

The Analytics

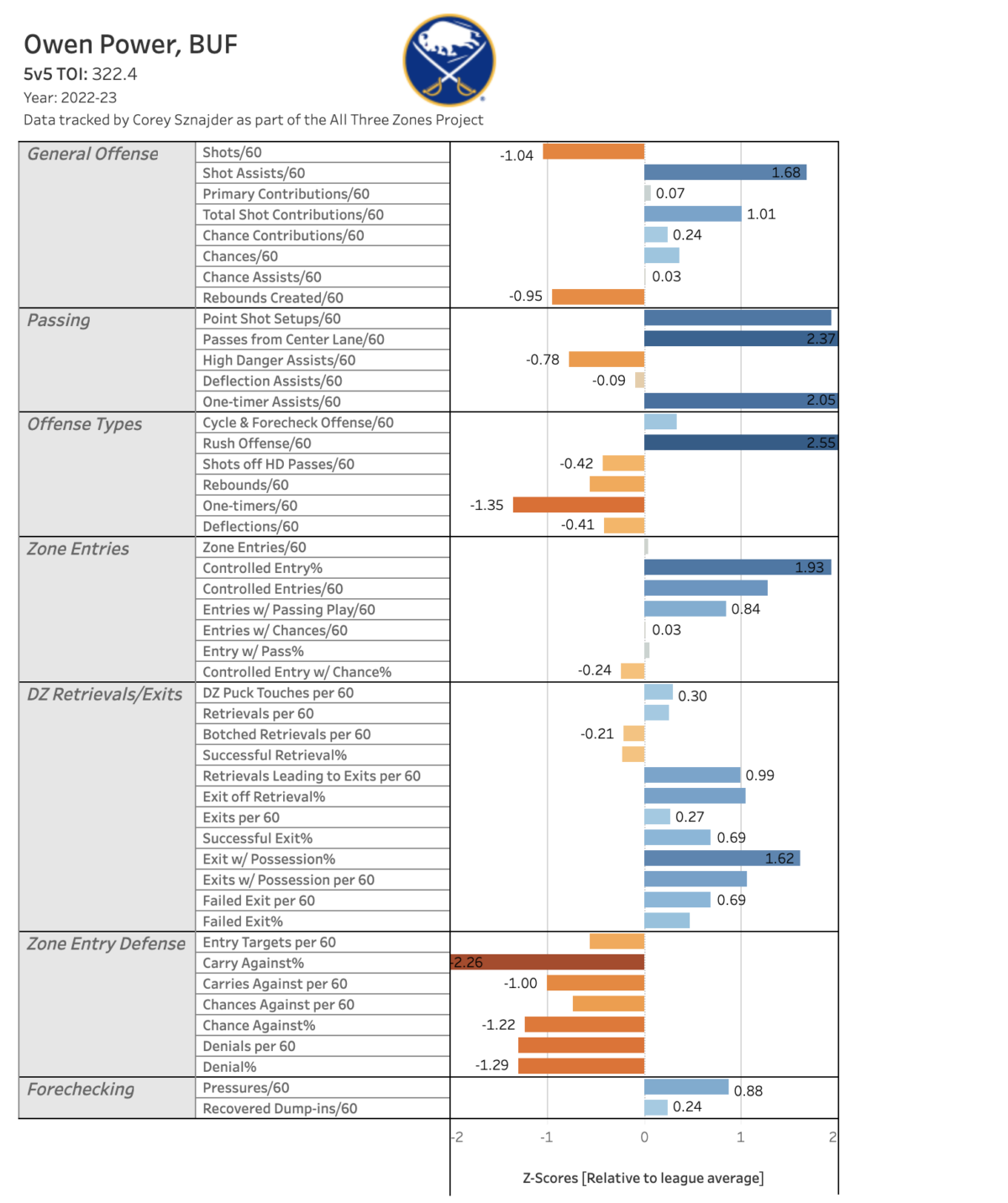

Statistical models frame Power as an elite force in transition and in the offensive zone. His passing ability and mobility translate onto the stat cards, which depict him as an incredibly effective, pass and rush-oriented play driver on defense who can’t really capitalize on chances of his own. Counting stats reflect this, too — he logged 35 assists in 79 games this past season, but just four goals. No one will argue his offensive prowess.

Where it gets muddy, though, is on the other end of the ice. Analytics show that Power’s defensive impacts leave a lot to be desired. Specifically speaking, the statistics show that he struggles mightily with zone entry defense, or the ability to prevent the opposition from entering the zone.

Whereas Power’s retrieval data is pretty solid — he only seems to struggle with the occasional blunder while getting the puck back in his own zone — his entry defense is allegedly abysmal. Relative to every other player in the league, this facet of his game seems to be a real struggle for him. As per NaturalStatTrick, the Sabres held a 49.73% expected goals-for percentage (xGF%) at even strength this year. Power, again struggles here statistically, showing up with a 47.98% xGF% despite strong offensive showings.

Considering that Power’s offensive game is seemingly so strong, and yet his xGF% is weak relative to even his teammates, shows that perhaps this tracked data comes to the correct conclusion. And yet, from the eye test, this really doesn’t make sense at all.

The Eye Test

It’s very easy to come up with excuses for why this analytical profile may be occurring. After all, Power was left with a revolving door of partners last season, was put on the ice in difficult situations often, and matched up against top players on a nightly basis.

Related: How Sabres’ Owen Power Can Avoid a Sophomore Slump

Past the potential excuses, though, watching replays of Sabres games also sows some doubt in the analytics community as to why his defensive impact is what it apparently is. Oftentimes, Power was left to fend for himself in odd-man situations, which inherently are more dangerous scoring chances than a cycling offense.

Throughout my experience looking back through games, I regularly saw Power get left alone to defend those odd-man rushes because his partner pinched at an inopportune time and cost the Sabres a scoring chance against. On top of that, Power’s partners seemed to puck-watch at a much higher rate than the average 24-minute-a-night defenseman. Take a look at this goal against the Sabres at the hands of the Florida Panthers.

In this clip, Power’s partner, Henri Jokiharju (who spent the most time with Power of any of his partners), gets roped in by Carter Verhaege, and puck-watches to the extreme in an attempt to get the puck away from the Panthers forward. In doing so, Jokiharju opens up a route for Sam Bennett to creep back into the center of the ice, where it’s much too late for Power to try and recover before Bennett scores on the high-danger chance.

Power, there, did mostly everything right. He tried to put himself in the passing lane between Bennett and Verhaege with the assumption that his partner would be in the right spot to break up the potential second pass if the puck were to go past Power. When it did, Jokijarju panicked and it cost the Sabres a goal against. This is exactly the type of play that I saw time and again with Power on the ice.

Then comes his deployment. Power was put into defensive-zone draws on over 56 percent of faceoffs, which inherently means that he and his linemates are more prone to giving up chances. Factor in that he oftentimes faced opposing teams’ top talents (his most-faced skaters were Hampus Lindholm, Charlie McAvoy, and Victor Hedman), and that point is only magnified.

It would be naive to say that Power doesn’t have issues of his own, though, even by the eye test. For starters, he’s prone to the occasional mishap with the puck — something that should be expected for a rookie NHLer who is bound to have some growing pains. As with someone his size, too, the skating ability leaves a bit to be desired. He’s not immobile, and for a 6-foot-6, 218-pound defenseman, he has somewhat decent speed; but that’s not to say he’s a great skater. He sometimes gets caught flatfooted and is incapable of catching up because of his lack of acceleration.

In addition to that, there’s the occasional mental blunder. Sometimes — not often — but sometimes, Power finds himself pausing with the puck to a fault, resulting in a turnover to the opposition, and somewhat frequently resulting in a goal against. Again, with someone new to the league, there are bound to be growing pains, and it is something that fans should assume will improve over the course of his career.

The Verdict

Unfortunately, there isn’t one “right” analysis here. Yes, there are reasons unrelated to Power that may lead to somewhat ugly underlying statistics. Yes, his partner rotation left some instability in his game. And yes, his deployment lent itself to tougher defensive assignments.

However, the numbers don’t lie. Even relative to his linemates — players who were also on the ice during Power’s partner’s defensive lapses — Power’s numbers are weak. There comes a point where the excuses just don’t cut it, and Power flat-out has to be better in his own end if he truly is to be the elite defenseman that most people expect him to be.

As someone who consistently backs analytics, and trusts that the numbers are a better indicator of success (or a lack thereof) than my own scouting ability, I do have to say that I have some reservations about trusting the numbers in this particular case. Power’s defensive impact has, at least as long as he’s been in the NHL, been a point of contention for the analytics community. There certainly is reason to believe that his defensive impacts are better than the on-paper results, and as such, I think it’s much more likely that they drastically improve than stagnate.