The Sharks have made major changes, which makes it disheartening to see the same, critical mistake happening again this season. With a new coaching group and a new approach to adding genuine talent via free agency, I thought one critical thing might change. Alas, the answer so far is a resounding ‘no’.

The Sharks, once again, continue to burn their top forwards with heavy ice time. It is an approach that may work to a degree early in the regular season, but can prove highly problematic later in the season and into the playoffs.

Optimal Performance?

Describing the problem is simple. Players each have an optimal amount of playing time. Once they pass that optimal peak, they offer diminishing returns. This can happen within a game and over the course of a season. It is very easy to describe the extremes. Very little playing time does not allow a player to accomplish much or develop chemistry with the team around him. Too much playing time and the player is simply too worn down to be effective. If players did not wear down, the best players on each team would be on the ice for 60 minutes a night. Each coach realizes that managing a player’s ice time is part of getting the best from that player.

With the Sharks, the problem is not that some forwards are relatively high in terms of ice time, it is a matter of which forwards are getting the major ice time. The top four Sharks forwards in terms of ice time are Joe Pavelski, Patrick Marleau, Joe Thornton and Joel Ward. These are not young players. Thornton and Marleau are 36, Ward 34 (turning 35 next week) and Pavelski 31. None of the players are old, but they are older and playing heavy minutes can create the problems described in this linked article on line balance. These issues can range from injuries to the ability to play fast in 3-on-3 overtime. It can even create second order effects, such as a player preserving energy early in a game to have something left for later in a game.

In a sport where being 0.01 seconds quicker can mean the difference between a goal or not, the cumulative effect of wear and tear can result a meaningful drop-off in play.

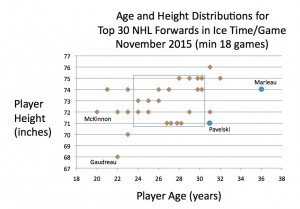

Towards the end of last season, I identified the top 30 forwards in terms of ice time. I then charted them by age and height to find the ‘sweet spot’. In theory, a bigger player might be able to handle more ice time due to being able to better handle the hits. A younger player should be able to bounce back more readily. I drew a box around the central values. The age range covered 15 years and the height range was six inches equaling 90 units (6×15=90). The sweet spot, however, was a box of 18 units, or just 20% of the chart area. This box captured 53% of the forwards. The borders of the box were between age 24 and 30 with a height between 72 and 75 inches (6’0″ – 6’3″). The center point was 6’1.5″ and 27 years old.

I have redone the graphic for this season and it is similar. The age range is now 16 years and the height range is eight inches (128 units). The median age is, once again, 27. The median height is 6’1″, about half-inch shorter than the prior year. In this case, I drew a box that covers heights from 71 inches to 75 inches and the same age range as last year’s box, from 24-30. This is 24 units, slightly under 20% of the chart area and is the graphic below. 60% of the players fall inside the box.

The graphic shows a few forwards that are quite far from the center of the range. The most notable are Johnny Gaudreau, whose small size stands apart and Patrick Marleau, whose age stands apart.

Also outside of the central box is Joe Pavelski. Pavelski’s style of play is admirable, but he takes a ton of punishment along the way. During this brilliant goal against Nashville, Pavelski is hit three times by three different Predators within a matter of moments. Can he withstand top minutes with his style of play?

If there is degradation in play based on ice time, it should find its way into the player’s statistics.

Does the Data Show Degradation?

In looking at older forwards with large ice time and how they fared over the year, I divided last season into two parts. The first part is October-December 2014, the second part is January-April 2015. Last season, Mike Ribeiro of Nashville was among the older forwards with a high ice time (29th among forwards). Ribeiro went plus-14 in the October-December 2014 part of the season, dropping to a minus-3 during the January-April 2015 part of the year. Daniel and Henrik Sedin both had modest declines, combined a plus-12 in the first part of last season, a plus-4 in the second part.

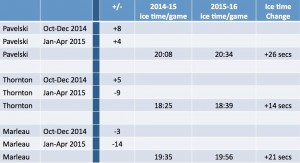

I consider a baseline ice time to be 78 games at 18 minutes per game for an excellent forward, which translates to 1404 minutes. Premium forwards in the prime of their career can go above that, but otherwise, this should be close to norm. Last season, 65 forwards met or exceeded 1404 minutes, roughly two per team. The Sharks had four forwards exceed that ice time. This season, Pavelski and Marleau are projecting to play 82 games at roughly 20 minutes per night. It is the equivalent of adding 14 NHL games to their ice time above the baseline. Joel Ward and Joe Thornton are also projected to exceed that baseline, though by smaller amounts. Last year, 11 forwards over age 32 surpassed that 1404 minute mark. Eight of the 11 showed a decline in their plus-minus in the second part of the season.

Since I have written before on this topic, I’ll borrow from earlier work. Back in March, I documented Marleau’s struggles from last season. I noted that these issues were not a ‘one time thing’. I used the last four seasons worth of data to compare Marleau’s results in the season’s first month and compared it to his results for the rest of the season. It showed that Marleau peaks in the first month of the season, with a dramatic drop-off over the rest of the season. By playing Marleau past the point of diminishing returns, the Sharks have taken a very talented player and compromised his performance.

For Thornton, Marleau and Pavelski, last season’s results are worth reviewing. In the case of all three players, their plus-minus diminished as the season went on. Combined, they were plus-10 in the first part of the year, during October-December 2014. In the second part, from January-April 2015, a combined minus-19.

Digging deeper, the points per game (PPG) were similar between the two parts of the season, with the power play a major part of their PPG numbers. It was on the defensive side of the ice where the numbers took a hard downward turn. If a player is wearing down, it is usually the defensive side of play that suffers first. The data strongly supports that. To date, none of the three players are seeing their ice time reduced this season. All have added at least 14 seconds per game over last season’s averages. Adding 14 seconds per game over an 82 game season is like adding an another game’s worth of ice time.

Risk versus Reward

Sharks coach Peter DeBoer currently stands alone in this league in the way he assigns minutes to his older players. Only five forwards in the top 30 in ice time per game are 31 or older, two of the five are Sharks: Pavelski and Marleau. Marleau, at 36, is the oldest forward in the top 30 in ice time per game — by four years (Mikko Koivu is the next oldest at 32). The next two Sharks forwards in ice time per game are Thornton (60th in the league among forwards who’ve played at least 18 games) and Ward (83rd).

With the Sharks players, it is straightforward to see the decline in play from the first part of the season to the second part of the season in the plus-minus numbers. It is a trend that is shown to be common with other similarly-aged forwards in the league. It is clear that DeBoer, like his predecessor Todd McLellan, feels comfortable pushing big minutes on his older forwards.

Some will argue there is minimal linkage between player minutes and player effectiveness for older players; that the effect is not related to the cause. I’ll simply disagree, there are too many examples to cite that support this relationship. I would suggest that those who want more rigorous evidence approach the issue from the other direction. Find the rigorous evidence that suggests this is not a problem. It seems arrogant for the Sharks to ignore a substantial amount of anecdotal evidence — including the evidence that should matter the most, the overwhelming evidence coming from their own players.

This sort of mistake may lead to optimism in December, when these talented players are at their best. But the real season begins in April. Like McLellan, I fear DeBoer is placing excessive emphasis on games 1-82. The critical need for this franchise is to be the best team they can possibly be for game 83. For the Sharks, an optimal season means advancing the furthest they can advance in the playoffs. To be rewarded with that optimal season, the team’s management needs to stop repeating their critical mistake.