The hockey world was coming off a global pandemic and the Stanley Cup was awarded in a neutral location. When the dust settled, Ottawa beat Seattle to claim Lord Stanley’s Cup. No, this is not science fiction or an alternative reality. It’s what happened 100 years ago.

The Ottawa Senators won the Stanley Cup with a 6-1 win in the deciding game over the Seattle Metropolitans, or, as the pundits of the day in 1920 would have said, it was ‘the Ottawas defeating the Seattles in the World’s Hockey Series.’ The world was indeed coming off a pandemic, as the Stanley Cup Final series had been cancelled in 1919 due to the Spanish Influenza. The series was moved to the artificial ice of the Arena Gardens in Toronto because of poor ice conditions in Ottawa.

A century ago, the Stanley Cup tournament featured the champions of the National Hockey League and the champions of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association in a best-of-five series.

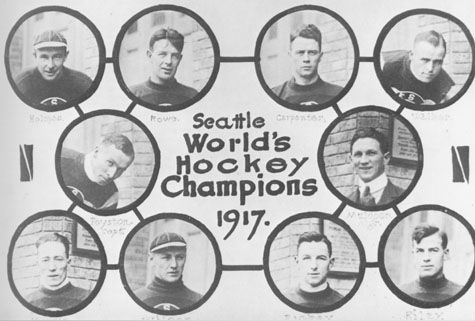

While Seattle may be an expansion market today, it was a big hockey city a century ago. The Metropolitans won the Stanley Cup in 1917, to become the first U.S. team to win the championship.

Since the Ottawa Senators were champions of both halves of the NHL season, they avoided a playoff series to determine the league champions. It was a four-team league that year, with the Senators, Toronto St. Patricks (now the Maple Leafs) and the Quebec Athletics.

The Metropolitans finished in first place in the PCHA, which was the first hockey league to introduce playoffs for the championship. The Metropolitans beat the second-place Vancouver Millionaires in a two-game total points series. Vancouver won the first game 3-0 in Seattle but lost the next 6-0 back in Vancouver. The other team in the three-team circuit was the Victoria Aristocrats.

World’s Hockey Series

Ottawa was excited to host what was then referred to as the World’s Hockey Series. NHL President Frank Calder announced an increase in ticket prices for the series. Reserved seats at the Arena on Laurier Ave. sold for $1.10, $1.60 and $2.20 per game, with general admission seating available for 55 cents. The prices included a war tax.

Seattle’s lineup was boosted by their top scorer from the previous season, Bernie Morris. Before the 1919 Stanley Cup Final, Morris was arrested for draft dodging and sentenced to two years of hard labor at Alcatraz. He was released after serving one year and headed straight to Ottawa for the series.

One player missing from Seattle’s 1917 Stanley Cup, however, was Cully Wilson, who was a star of the day. Born in Winnipeg as Karl Wilhons Erlendson to Icelandic parents – his family changed its name to Wilson in Winnipeg – Cully Wilson became one of hockey’s biggest stars in the 1910s.

He was a talented but rough player and was banned from the PCHA after the 1919 season and returned to Toronto, where he played in the NHL for the St. Patrick’s. The gifted goal scorer also led three different pro leagues (NHA, PCHA and NHL) in penalty minutes during his career. The Senators had to get past Wilson and the St. Patrick’s to win the NHL title and a chance to play for the Stanley Cup.

The Senators had to find alternate sweaters since their white, red and black striped sweaters were almost identical to the white, red and green striped sweaters of the Metropolitans. Ottawa decided to wear all white sweaters with an embroidered red “O” for the series. They also changed their socks to white with one black and red stripe, because of the similarity to Seattle’s uniform.

A New Kind of Hat Trick

Football star Jess Abelson of the Ottawa Rough Riders, who had just opened up a men’s clothing store on Sparks Street, offered some incentive to Ottawa’s players. Abelson offered a Borsalino hat to the member of the Ottawas who scored the most goals in the World’s Hockey Series.

He also offered a new tie to the player of either team who scored the first goal of the series. Abelson was a legend in Ottawa sports and a national rowing champion. A generation later, he was the first person inducted into the Ottawa Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. He is also in Ottawa’s Sports Hall of Fame.

When the Metropolitans arrived at Ottawa’s Central Station the day before Game 1, they were greeted by a crowd of Ottawa fans who welcomed them with an ovation. Receiving a particularly warm welcome was Seattle defenceman Roy Rickey, an Ottawa native who grew up playing in the city’s church league.

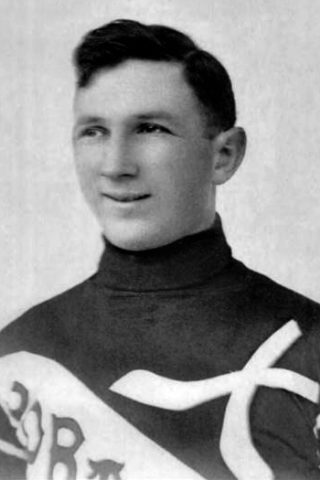

A sold-out crowd of 7,500 fans saw the first game of the series. At the time, it was one of the largest crowds in the history of the sport. The Senators came from behind to beat the Metropolitans 3-2. Seattle star Frank Foyston opened the scoring and earned himself Mr. Abelson’s finest tie as he beat Ottawa goalie Clint Benedict with a long shot that went past the defencemen and beat the Ottawa goalie.

Foyston made it 2-0 in the second. Rickey carried the puck up the ice and was knocked down by a hard body check. He managed to get the puck to Foyston, who skated in on Benedict and beat him for Seattle’s second goal.

Ottawa grabbed the momentum in the second half of the game. Frank Nighbor outbattled Foyston for a face-off at the 13-minute mark of the second and put the puck past the Seattle goalie Harry “Hap” Holmes.

Nighbor tied the game midway in the third, setting the table for a dramatic finish. Ottawa captain Eddie Gerard led a three-man rush late in the game. His shot was stopped by Holmes, but Jack Darragh pounced on the rebound and scored. Ottawa played a tight, defensive game the rest of the way and Benedict was solid as the Ottawas took the first game.

7-Man Hockey

Game 2 was a challenge for Ottawa. The game was played under PCHA rules, which included a seventh man on the ice and forward passes in the centre ice area. The game was also played on wet, soft ice since the arena in Ottawa did not have artificial ice, and Canada’s capital was experiencing mild weather.

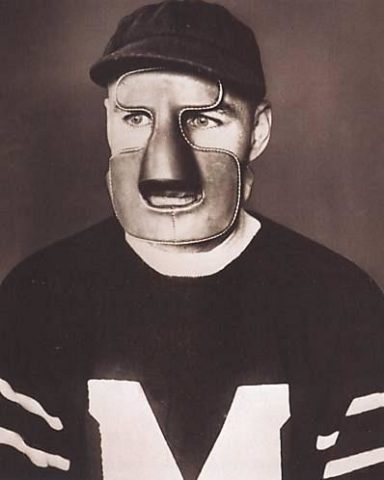

Clint Benedict earned a shutout in the second game to give Ottawa a 3-0 win and a 2-0 lead in the series. Later in his career, Benedict became famous as the first goalie in the NHL to wear a mask when he was with the Montreal Maroons.

Jack Darragh scored the first goal in the first period, whirling around the net and coming out front to slap one past Holmes. In the third, Ottawa pulled away as Eddie Gerard shot the puck past Holmes on a rush. George Boucher used fancy stickhandling to dash through the Seattles before beating Holmes for Ottawa’s third goal of the night.

Seattle Stays Alive

The big story in Game 3 was the poor ice. The teams played in slush, and media reports indicated that some players’ skates were cutting through the slushy, soft ice. Ottawa stars Jack Darragh and Frank Nighbor left the game exhausted from the ice conditions. But the big trio for the Metropolitans, Walker, Foyston and Holmes, persevered and kept the Seattles alive with a 3-1 win.

The game opened up with a ceremonial face-off. Canadian lumber pioneer J.R. Booth, a 94-year-old hockey fan who had been to the other World’s Hockey Series games, dropped the puck to a rousing ovation from the fans and players from both teams. As the game started, Ottawa scored first, and it looked like they were ready for a Stanley Cup sweep.

“Eddie Gerard and his Senators broke from the barrier like flashes and were soon buzzing around the Seattle nets,” the Ottawa Citizen recalled. “Harry Holmes turned shot after shot aside with amazing coolness, but the Ottawas were not to be denied and in five minutes Frank Nighbor rushed and slipped the puck over to George Boucher who drove a hard one, got the rebound and slapped it back late in the nets, amidst a thundering outbreak of applause,” (from ‘Fourth Game In World’s Series Transferred to Toronto Ice, Will Be Played Tomorrow’, Ottawa Citizen – 3/29/1920).

A Stanley Cup celebration in Ottawa, however, was not in the cards. Late in the first period, Foyston raced down the right side and took a feed from Jack Riley. He beat Benedict to tie the score at 1-1. In the second period, both goalies were impressive in stopping numerous shots. Seattle finally took the lead late in the frame when Jack Walker rushed down the centre of the ice and fired a short pass to Foyston. Benedict got a piece of Foyston’s shot, but it caromed off his skate boot and into the net to give the Mets a 2-1 lead.

Ottawa native Roy Rickey, meanwhile, was having a tremendous game for Seattle. He and defence partner Bobby Rowe threw up a stone wall that the tiring Senators forwards could not penetrate. Appropriately, it was Ricky who took a feed from Walker and drove a shot past Benedict to clinch the 3-1 win.

After the game, NHL President Frank Calder announced that the remainder of the series would be played in Toronto, on artificial ice. The Allan Cup was being played at the arena, with the Winnipeg Falcons defeating the University of Toronto for the amateur championship of Canada and for the right to represent Canada at the Antwerp Olympics.

Series Moved to Toronto

Game 4 was played at the Arena Gardens in Toronto on March 31, 1920. The PCHA rules were in place, and Seattle took full advantage with a 5-2 win. In their game report on the front page of the next day’s newspaper, the Ottawa Journal was critical of the western rules and its forward passing:

“The Pacific coast teams introduce new plays every season, and for this reason if for no other it is interesting to see them in action,” the front-page story of the Journal noted on April 1, 1920. “Their forward passing has a lot of good points in its favor, but it puts a premium on loafing, and does not encourage the back-checking perfected by eastern teams.

Foyston, the centre position player, seldom went back with the Ottawa rushes. When he failed to locate the rushes with his clever poke-check, he rested on his cars, and waited for one of his teammates to carry the puck to the red line and pass it forward to him,” (from ‘Ice Conditions Praised For Fifth and Final Match in Toronto’, Ottawa Journal – 4/1/1920).

Foyston and Walker were stalwarts, while Rowe and Riley continued to play well defensively for Seattle. Foyston finished the game with two goals, while Rowe, Walker and Rickey each added one. Frank Nighbor scored both Ottawa goals.

Ottawa Wins Deciding Game

Despite the neutral site, another big crowd turned out for the deciding game of the series in Toronto. Seattle fans who had come to Ottawa made the trip, as did many from Ottawa. There were also fans from Toronto in attendance.

Seattle scored first on an end-to-end rush by Bobby Rowe, but Ottawa tied the game in the second and added five in the third to decide the Cup with a 6-1 win. George Boucher tied the game with an end-to-end rush in the second period. In the third, Jack Darragh emerged as a hero with three goals, while Eddie Gerard and Frank Nighbor each had one.

Nighbor’s goal was his sixth to lead the team and win the hat from Jess Abelson’s store. After the game, the Senators were given a cheque by Calder from which the players earned $390.19 each. The Seattle players each received $319.39.

Ottawa GM and part-owner Tommy Gorman forgot to have his 1920 championship team and name engraved on the Stanley Cup. The 1920 Senators were not added to the Cup until it was redesigned with a new collar in 1948.

Seattle coach Pete Muldoon said he was looking forward to a rematch with the Senators. “We want you fellows out on the Coast next year and we will take that old cup away from you,” Muldoon said after the game, as reported by the Ottawa Citizen (from ‘Senators Win Deciding Game Against Western Champions By Score of 6 to 1 in Strenuously Contested Match at Toronto’, Ottawa Citizen – 4/2/1920).

The rematch never happened. The 1920 Seattle Metropolitans was the last U.S. west coast team to play for the Stanley Cup until Wayne Gretzky and the Kings faced the Montreal Canadiens in 1993.

Perhaps the Ottawa-Seattle rivalry is long gone. But we know that when it is renewed, there will be six men per side, a lot of forward passing, and the ice will be hard and fast.