Brent Burns, the talented defenseman for San Jose Sharks, is a remarkable athlete.

Burns leads all NHL defensemen in a variety of areas, including goals, even strength goals and shots — all by large margins. At the same time, he is also among the worst players in the league in terms of goals allowed. When Burns is on the ice at even strength, the Sharks are far more likely to give up a goal as compared to their team average. Surprisingly, given his offensive talent, the Sharks are also far less likely to score a goal. His tremendous athleticism has not translated to enough ‘goodness’ for the Sharks at even strength. And lest I be accused of forgetting his superb work on the power play, he also leads NHL defensemen in power play points.

Much has been written about Brent Burns, including articles are here, here and here. Instead of approaching this piece with heavy emphasis on the usual statistics, I’m going to look at this from different points of view. In the process, we’ll look at conventional wisdom (it doesn’t fare well) and examine the underlying issues that can limit a great talent. We will also do a more rigorous job of defining the conundrum and identify two possibilities to exit it, one often mentioned, the other so rare that I don’t think it has been discussed yet in this context. I’ll begin by looking at Burns through the lens of another sport.

Comparisons to non-Hockey Players

I’ve tried to equate Burns to players in other sports and two names that came up were basketball players Magic Johnson and Shaquille O’Neal. I recall an analyst once describing O’Neal as being so big and so strong that he ‘distorted the game’. That is when he was on the basketball court, the game had to be played differently. The distortion even changed the officiating. It was essentially impossible to officiate O’Neal under the same rules everyone else played under without ruining the game.

In the case of Magic Johnson, no one had ever seen a player that had his combination of high-end skills. He could dribble like a small quick point guard, but he could rebound like power forward.

Both Johnson and O’Neal were unlike any other player of their era. When I look around the NHL, Burns is unlike any other player.

Like Magic Johnson, Burns is amazingly agile for a big man. Burns, like O’Neal, is exceptionally strong. Both Burns and O’Neal brought important liabilities to their game. O’Neal’s free throw shooting was so abysmal that his team was reluctant to play him near the end of close games for fear the other team would simply foul him.

One person highlighted Burns’ liabilities by comparing him to a 747: incredibly powerful going forward but requiring help to go backwards. Burns aggressiveness has a tendency to create low percentage plays and he is simply not good defensively in specific, but unavoidable, situations.

Understanding the assets and liabilities of unique, top-end players, allow them to be used more effectively. So that is where we’ll go next.

Burns Assets

Burns possesses incredible mobility and agility when going forward. He has a terrific shot. Whether it comes from the point or elsewhere, Burns ability to fire the puck has three elements. He settles the puck remarkably quickly, is brilliant at creating shooting lanes and fires it with incredible power despite almost no wind up. The quickness and power of his wrist shot is the best in hockey.

Burns skates well and he skates powerfully. He moves the puck well. The same skills that allow him to fire pucks on net also allow him to make quick passes. He is a physical mismatch for the vast majority of the players in the NHL.

Burns carries a big personality. He often comes across as a playful kid, doing silly or unusual things in interviews. From his hair, to his tattoos to his snake collection, he is his own man. What comes across in his play is his passion. There is no shortage of work ethic or determination. Burns is a high-energy person with a big persona. Despite his struggles to play a disciplined position in a team game, he is not a prima donna. He is a player that wants to win and will work hard to make that happen. That matters, a lot.

Two More Key Assets

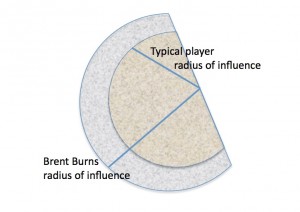

I’ll take a couple of paragraphs to describe two critical but rarely discussed aspect of Burns’ game. I consider Burns to be a ‘big radius’ player. When I think of a player and the area he impacts, I think of it as a semi-circle. He influences the play where he is standing, but also approximately 90 degrees to the right and to the left. The area influenced is a function of the radius squared. A player with a six-foot radius will impact an area 44% greater than a player with a five-foot radius.

The radius of that semi-circle for Burns is good a bit larger than for most players.

His long reach combined with a long stick means he is able to directly affect play covering a radius perhaps a foot (or more) greater than most players. His athleticism adds to it because he can move quickly. All players lose power as they extend their reach (hence the adage about keeping one’s nose over the puck). When Burns reaches, he seems to retain a lot more power than most players. Trying to clear a zone or complete a cross-ice pass with Burns anywhere in the vicinity is a challenging task. By cutting off so many angles with his length, Burns restricts the choices available to opposing players. His radius allows him to execute a pokecheck from a distance that other players would not even consider trying. It can come in handy trying to break up odd man rushes, forcing offsides on entries and blocking shots. On the penalty kill, Burns uses that radius to take away time and space effectively. A couple other big radius players I’ll mention along with a benefit it brought them. It was incredibly difficult to clear a puck on the side Chris Pronger was patrolling. Burns’ teammate, forward Joe Thornton, is able to control the puck away from his body, allowing him added time and space to make passes.

The second aspect of Burns game that rarely gets mentioned is his forecheck. He might have the best forecheck in the NHL. His size and power are among the best in hockey. Since Burns also maneuvers quickly when he is going forward, he gets in on the forecheck quickly. And with his radius, once he starts closing in, the player with the puck usually has few good choices since Burns cuts off so many angles for moving the puck. Burns is no fun to play against along the boards or in the corners. Even against players that are close to him in size, Burns is often able to throw them around like a rag doll. This leaves the player trying to advance the puck with unenviable choices. One choice, the player can try to pass it despite having limited angles with which to work. This means there is a high risk of a turnover in an area you really don’t want to turn it over. The other choice is to keep the puck and battle with the bigger, stronger Burns after he crashes into you like a ton of bricks. When Burns is closing in on a forecheck, good choices for the opponent are few and far between.

Defying Conventional Wisdom

There is a saying often used in hockey, “its never a bad play to put the puck on net”.

But with Brent Burns, that does not seem to be the case. Burns has 11 even strength goals to lead NHL defensemen. However, his other teammates have combined for only nine even strength goals with him on the ice. That is just 20 goals total. Brenden Dillon, hardly an offensive force (with considerably less playing time) has been on the ice for 23 even strength goals. Burns has taken over four times the number of shots as Dillon, yet the Sharks score more with Dillon on the ice.

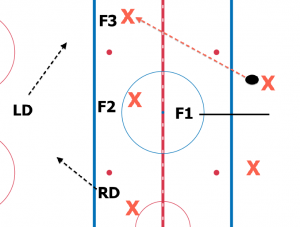

I’ll recount a possession where Burns put multiple shots towards the goal (at even strength) in the Sharks most recent game against Winnipeg. Burns managed three shots from the the point on that shift. The first two were both redirected wide to the short side where the Sharks recovered the puck against a scrambling defense. Each time, the puck was worked back to Burns at the point. On Burns third shot, a long rebound went to the mid-slot and onto the stick of one of the Jets, who promptly cleared the zone. It looked a lot more dangerous than it really was.

What does this tell us? It tells us that when Burns shoots the puck, either it goes in for a goal or it doesn’t do much for the team’s offense. Why is that? The answer is both simple and unappealing. The Sharks system is not well suited to take advantage of a Burns miss. Unless the shot goes in, a Burns shot is a very low percentage play, defying hockey’s conventional wisdom.

Could the Sharks adjust their system to make Burns point shot a more valuable weapon? Of course they could, but there is a danger in creating a ‘Burns specific’ system.

Understanding A System

When a coach puts in a system in hockey, it comes with very different assumptions than a system in basketball. One in particular matters in our context. In basketball, the playing time is dominated by a small number of players. In basketball, a system needs to accommodate the 5-7 players who dominate the playing time. In hockey, on most nights, 18 players skate. It is likely that every player will skate at least a bit with every other skater. With so many combinations, having a system that everyone can follow is considered essential. The system sets out responsibilities, where to position yourself, what pass to make, when to pinch, when to change, etc. A system can be thought of as a set of structured rules: If you experience ‘this’, do ‘that’. Rules allow a player’s thinking process to happen faster. It is, in effect, a mental short cut. If done well, actions and reactions appear instinctive as the system becomes ingrained.

At this point, I’ll introduce an insight from former Shark (for a few seasons) and Hall of Famer Igor Larionov (Lariononv is pictured below, on the right, with Glenn Anderson). In an intriguing piece, Larionov wrote, “We had a saying in the Soviet days that I wish more coaches and scouts would adopt today: It’s not how fast you skate, it’s how fast you think.”

http://gty.im/83630701

To the extent players follow a given set of rules, the more interchangeable they become. Systems are designed to help players ‘think fast’. Given that hockey has all sorts of situations that call for player changes (injuries, slumps, specialty play, etc), player interchangeability has become a critical, if poorly understood part of the game. The need for interchangeability is what drives the need for a single uniform system. A system must address the needs of the all the players; there is a ‘lowest common denominator’ aspect to a system.

In basketball, creating a system around the talents of Magic Johnson made sense. He’d be out on the court 80% of the playing time. Creating a system around any hockey player, where few players exceed 40% playing time, is far less appealing. A system built around Burns unique abilities (or that of any top end hockey player) would almost certainly lead to problems for the 60% of the time Burns is not out on the ice.

Systems can respond well to great talent as long as the talent fits the system. A very fast hockey player will fit a system. Systems do not respond well to highly differentiated talents. Burns is a highly differentiated talent.

Perhaps no recent play demonstrates what happens when a system implodes more than Burns’ skate against the Flyers the other day. In the video below, it occurs at he 0:40 mark. In this play, Burns takes a pass that was tricky to handle. What follows is an attempt by Burns to create something. It is easy to get transfixed on Burns while watching the play, but I’d suggest you watch the other Sharks players. It is obvious, they have no idea what Burns is going to do next. They also have no idea what they need to do next. At that moment, there is no system. It is the antithesis of Larionov’s “thinking fast”. The result winds up being a rarely seen 3-on-0 breakaway against the Sharks.

What Position?

There are nominally two positions Burns can occupy in 5-on-5 hockey, right-handed shot defenseman or as a wing on a forward line. The case for him to be a winger has been made repeatedly, here and here, among many other places. By moving him to forward, you remove his most problematic defensive liabilities and his most problematic offensive/transition issues (over-committing). You also allow him to use his top skill, the forecheck, far more often.

There is however, another possibility. Invent something new for Burns, as the Lakers did with Magic Johnson. As discussed above, inventing a system to account for single player’s skill in hockey has far different ramifications than in basketball.

Unless …

Is there a way around the system approach to hockey, where you could build a system to surround a player without compromising the rest of the players? The answer is yes, but it is rarely used. The Sharks have employed such a system before, albeit far back in their team’s history.

I’ll return to Igor Larionov’s article where he describes the current game as system driven, one where coaches are constantly encouraging players to conform. He examines the downside that a system forces on creative, uniquely skilled players. In his case, he developed in a system under the strict discipline of the USSR, but ironically enough, encouraged creativity on the ice. Larionov wrote:

Many young players who are intelligent and can see the game four moves ahead are not valued. They’re told “simple, simple, simple.”

While Larionov does not say it, this is driven by the need for player interchangeability. In Larionov’s case, while playing back in the Soviet Union, he developed great chemistry with long time teammates. How good was it? Larionov described this way:

You didn’t have to see your linemate. You could smell him. Honestly, we probably could have played blind.

Larionov managed to bring that mindset to San Jose in 1993. Instead of allowing rookie Sharks coach Kevin Constantine to develop an interchangeable system, Larionov threw his weight around. Larionov pushed for and got a dedicated five man unit that was not designed to be interchangeable with the rest of the team. The unit consisted of Larianov, his longtime Soviet linemate Sergei Makarov (who was older than Constantine), winger Johan Garpenlov along with defensemen Jeff Norton and Sandis Ozolinsh. In essence, those five were free to create and play their own system, independent of what the rest of team was instructed to do. It worked, as the Sharks were dramatically better (improving 58 points in one year!), even winning a playoff series in each of the two full seasons Larionov played in San Jose.

Maybe the time has come to revive this concept. The San Jose Sharks have an incredible and unique talent in Brent Burns. Sharks head coach Peter DeBoer can scrap the system he employs in the case of Burns and create a dedicated five player group with Burns as its centerpiece. In such a scenario, I would suggest DeBoer think long-term, and put guys around Burns that he can expect to stay together for several seasons. I’d suggest players that are at least 25, but no older than 32. Among the players in this age range are:

Logan Couture, Tommy Wingels, Joe Pavelski, Justin Braun, Marc-Edouard Vlasic and Brenden Dillon.

Once he determines a five-man unit, these players can create a new system, devoid of any relationship to the system employed by the rest of the team. Even the names of the positions can change. Burns, for example, could be a rover, not a forward, not a defenseman.

This sort of solution carries risk, but really, what is the downside? The Sharks have more losses than wins and perhaps the only thing positive about their record to date is that their competitors in the Pacific Division happen to be doing roughly as well as the Sharks.

Solving the Conundrum

The Brent Burns Conundrum can be summarized as follows: An incredibly talented athlete is being forced to play a role within a system ill-suited to his immense talents. His role in the system is one that overexposes his liabilities and underutilizes his assets. The system is driven by the need for player interchangeability, not for fully utilizing the skills and talents of an athlete who is both well above and well outside the normal variations.

The Brent Burns Conundrum can not be solved until one thing happens – the Sharks must recognize they are in a conundrum. Perhaps that is happening behind the scenes. It is not happening in public, where Sharks leadership is fully on board with how things are going now.

The team is squandering one of the most unique assets in all of hockey. It does not need to continue this way.

The simple way to stop squandering Burns is to find him a role which brings out his assets and limits his liabilities. Forward allows him to become an aggressive forechecker and use his incredible shot from closer in. It allows him to use his assets more. It also means he won’t be trying to sort out rushes or trying to decide when to pinch. He won’t be skating around the high slot with teammates trying to figure out what the heck he is doing. A position change allows him to limit his exposure to situations where his liabilities show up.

Alternatively, the Sharks could make an unusual move and dedicate a system to Burns and some select teammates. Is Burns a unique enough and superior enough talent to justify such a major move? I’m not convinced of it, but it is worthy of consideration. A similar move took place over 20 years ago and paid dividends for the Sharks.

The Sharks have put artificial constraints on themselves, in particular, when it comes to their most physically gifted player. The Sharks are doing the player and the team a disservice by constraining their best athlete to a role within a system that is a poor fit for the player. Shaking off these constraints off can change the trajectory of this team.