by Jas Faulkner, contributing editor

Gaet Lepine, the Timmins bartender who gave Connors his start as a professional musician, would remain a friend and collaborator of the performer for the rest of his life. Maintaining such a connection over the years was typical of Stompin’ Tom Connors. An important part of his larger than life story was that he never forgot the kindnesses afforded him as he made his way from hardscrabble beginnings as the child of an unwed convict to foster care with a family on Prince Edward Island to a young drifter who fell in love with the country he wandered from coast to coast.

When Connors met Lepine, he didn’t have the funds in hand for the beer he had just consumed. The bartender was faced with the choice between raising a ruckus over a nickle or offering some compassion towards the young man walked through the first third of his life with little more than the guitar he carried with him. Neither of them realised this incident was the start of a career that would give the hockey world one of three iconic songs about the game.

That song might not have ever happened if Connors, who was hitchhiking across the country, had the money to cover his bar tab. That night, Lepine agreed to let him sing for his supper. He ended up performing at the hotel bar for the next year. As his reputation grew, he enjoyed positive critical attention for his records and radio appearances. By age thirty, Connors was figurative and literal miles from from where he started.

You’ve most likely heard “The Hockey Song,” (also known as “The Good Old Hockey Game”.) It was just one of many tunes created by or associated with Connors that would eventually become entrenched in Canada’s pop culture. Connors’ recording career spanned from 1967 to 2008 and netted him one gold record, two platinum discs, and one recording that went double platinum. Aside from “The Good Old Hockey Game” he was known for writing (and sometimes co-writing with his friend Lepine) “Sudbury Saturday Night”, “Big Joe Mufferaw”, “The Black Donneys”, “Bud the Spud”, and a Canadian adaptation of the Australian standard, “I’ve Been Everywhere”.

The last song on that list of hits could have served as the theme for a film version of Connors’ life. He set the standard for anyone aspiring to be a Canadian vox populi by focusing his creative energy on the history and lore of Canada from the viewpoint of the people who lived it and kept those narratives alive in the retelling. At the behest of CBC, he traveled the country in 1974, visiting with people from all walks of life. The resulting miniseries, “Stompin Tom’s Canada” preserved an ethnographic/geographic picture of a cross section of the country and her people.

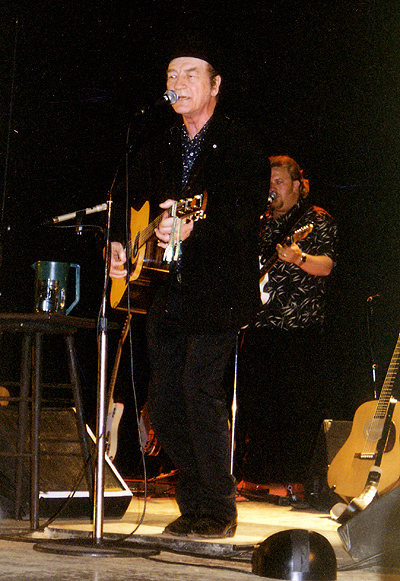

Charles Thomas Connors (later called Stompin’ Tom because of his habit of beating out the time as he played by stomping his feet) was by many accounts “an easy goin’ fella who never met a stranger.” However, in middle age he was sometimes viewed as a gadfly because of his protests that Canadian mass media was becoming too Americanized. Connors was a staunch believer in the preservation of Canada’s stories and lobbied to create stricter standards when it came to defining what was and wasn’t native content when it came to governmental funding and industry recognition. To him, a Canadian artist was someone who lived and worked in his or her home country.

His frustration over this difference of opinion led to his retreat to rural Ontario and an act of protest that made him a part of the national lore he worked to preserve. In 1978, Connors gave back all six of his Junos to express his displeasure at the rubric used by CARAS (the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences) to determine eligibility for the award.

And then he retired.

Sort of.

Prosperity gave him the financial cushion he needed to walk away. Still, thirty-eight is a fairly tender age for retirement. In retrospect, it seems uncharacteristic that the man who wore hats as a television presenter, folklorist, Goodwill Ambassador, and all around prickly critic of the establishment would stay so private for so long.

Credit (or blame, if you’re so inclined) for bringing Connors out of retirement belongs to two members of the indie rock band, The Rheostatics. Tim Vesely and Dave Bidini slipped into Connors’ fiftieth birthday celebration, wrote about the experience, and the university students who had made Stompin’ Tom a college radio staple pulled him back into the limelight.

birthday celebration, wrote about the experience, and the university students who had made Stompin’ Tom a college radio staple pulled him back into the limelight.

Connors’ post-retirement recordings are marked by slicker production values, but they maintain the spirit of old school country music that made him a part of national pop culture in previous decades.

The man who once told the CBC they “could take an offer to let him sing on someone else’s show and shove it” seems like a perfect fit to write the country song that would become a part of nearly every NHL arena playlist. I asked a hand full of fans -all of them fifty and under- if they knew how long the song had been around and who used it first. No one got it right. No one knew when or where Connors’ song became so married to the league. Most placed it a decade or more earlier and gave the honor to one of the two Original Six teams located in Canada.

Here’s the gospel when it comes to “The Hockey Song”:

Scotiabank Place, home of the Ottawa Senators, was the first NHL venue to add the song to their playlist. The next club to adopt it was Toronto. After that, it was a matter of time before fan requests and covetous arena managers around the league would nick the song for their own event lineups. And the year? 1997, a year shy of a quarter century after it was first released.

That the song would take the same meandering route to it’s rightful place as its creator is rather fitting.

It is also fitting that tonight, tomorrow night, and for a long time to come, the bombast of Nickleback and the aural shenanigans of Dropkick Murphys will always have the quietly archaic counterpoint of one man with an acoustic guitar stomping out the beat to a song that feels as timeless and rooted in hockey history as a game of shinny at Long Pond.

Stick taps to you, Stompin’ Tom.