In 2011, the hockey world was stunned by three deaths. Wade Belak, 35, hanged himself in his hotel room. Rick Rypien, 27, committed suicide in his home. And Derek Boogaard, 28, died from a lethal mixture of painkillers and alcohol. All three were NHL enforcers who liked to drop their gloves, and all three ultimately lost their struggles with depression.

The similarities among them hinted at a much larger problem. Georges Laraque, a former enforcer himself, said in 2011: “A lot of people can’t deal with the pressure in their minds and they use drugs and alcohol to deal with that. The three players that passed away, there are another 50 of them that used to be heavyweights and have problems with alcohol and drugs because of that role.”

Such off-ice struggles with depression and substance abuse are, most likely, the natural byproduct of fighting in the NHL.

A postmortem examination of Derek Boogaard’s brain showed he suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (or “CTE”). CTE is a degenerative disease of the brain caused by repeated blows to the head and concussions. Previously, CTE was called “dementia pugilistica,” since it was only seen among boxers. And when it comes to head trauma, NHL enforcers are basically boxers.

The symptoms of CTE are progressive, and they tend to mimic those of dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease, including memory loss, confusion, cognitive decline, visual problems, depression, and aggression. These symptoms can have a devastating impact on a person’s life.

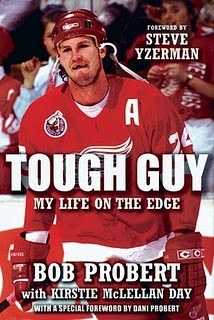

The only way to definitively diagnose CTE, even today, is through a postmortem examination of the brain. So we don’t know if Wade Belak or Rick Rypien had CTE, because tests were not performed on their brains. But researchers did look at the brain of Bob Probert, one of the NHL’s most notorious enforcers (still ranked fifth all-time in total penalty minutes), as well as Reggie Fleming, an enforcer who played in the NHL in the 1960s. Like Boogaard, both Probert and Fleming had CTE.

All of these revelations came on the heels of the NHL’s new efforts to curb concussions. The league had already completely revised its concussion protocols and instituted new penalties for dangerous hits that target the head. The time was seemingly right for the NHL to take a serious look at fighting’s place in the game.

The NHL’s executive vice president and director of hockey operations, Colin Campbell, stated that “we intend to continue to review all aspects of our game, with a focus on making it as safe as it can be for our players.” NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman added, “we’re going to continue to look at what we can do to keep the game physical but safe as possible.”

These were, in all fairness, lies. The NHL has not taken any serious look at fighting’s place in the game. Instead, the league has consistently dismissed both the dangers of fighting and calls for its ban:

Maybe it is [dangerous] and maybe it’s not. You don’t know that for a fact and it’s something we continue to monitor. The level of concussions from fighting is not rising, it’s constant, so it’s not an increasing problem.

– Bettman in 2011.

No damage done. Nobody gets hurt, [fighting] takes down the temperature.

– Bettman in 2013.

[Fighting is] an overblown issue because it’s a small part of the game, and to the extent there are concussions it’s a small part of that.

– Bettman in 2014.

At least he’s consistent. The league says its hesitancy to ban fighting is based on a lack of hard science confirming the link between fighting and CTE. Here’s Bettman again:

I think people need to take a deep breath and not overreact. . . . The data [are] not sufficient to draw a conclusion. Our experts tell us the same thing. You don’t have a broad enough database to make that assumption or conclusion [that fighting led to CTE or premature deaths] because you don’t know what else these players might have had in common, if anything. . . . I think it’s unfortunate that people use tragedies to jump to conclusions that probably at this stage aren’t supported.

The league’s general managers also prefer this wait-and-see approach; they “like [fighting] the way it is.” And there’s virtually no support from the players for a ban.

The problem, however, is that if fighting does lead to CTE, players will likely suffer irreversible brain damage while the NHL waits, perhaps indefinitely, for some sort of scientific consensus. And that scientific breakthrough likely cannot occur without players dying so researchers can examine their brains for CTE. That the NHL is comfortable with this — indefinitely doing nothing, exposing players to a serious risk, and waiting around for them to die — is shocking.

![Bloodied Rob Ray after a fight with Donald Brashear. [photo: H. Rumph, Jr.]](https://s3951.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Rob-Ray-214x300.jpg)

I can see the inconsistency . . . . I would say there’s no more evidence that fighting is bad for the brain than there is that hits to the head are bad for the brain. The amount of evidence is the same — essentially, very little. Yet the decision was made on a policy level: let’s take head shots out of the game. There’s no more evidence, or less, for head shots than there is for fighting.

So while head shots were an expendable nuisance, fighting is apparently “part of the game, it always has [been], and I think it always will be,” said Ottawa Senators forward Chris Neil. This a questionable distinction. Fighting is arguably just as unnecessary and dangerous as head shots. It’s just that the players and the league like fighting and will apparently go to great lengths to defend it.

They have their reasons; whether or not they are any good is another matter. Take the deterrence argument, for example. “I think when fighting’s out of the game then everyone’s going to be taken off on stretchers because of hits from behind and high-sticks and dirty checks,” said Buffalo Sabres enforcer John Scott. (Bobby Orr certainly would agree.)

The deterrence benefits of fighting are likely vastly overstated. For one, fighting probably causes far more injuries than it could ever prevent, injuries such as concussions, CTE, broken necks, and even death. And players can go over the edge trying to police each other. That is how you get Todd Bertuzzi breaking 3 vertebrae in Steve Moore’s neck, or Marty Mcsorley taking a baseball swing to the head of Donald Brashear.

The deterrence argument also minimizes the roles of referees and the league in handing down discipline. Dirty players can and should be punished by league officials. That is their job, and they do it well. But even if they did their job poorly, that would be an argument for improving the officiating, not for utilizing enforcers.

Moreover, North American college hockey, European hockey, and even the Olympics have more severe penalties designed to eliminate fighting from the game. In the NCAA, for example, a fight results in an automatic ejection and a suspension that increases with each additional fight. In none of these leagues, however, is there any evidence of an epidemic of dirty plays. Ultimately, if a similar ban were implemented in the NHL today, there would most likely be a net reduction in serious injuries, not an increase.

A related argument is that fighting is necessary to make room for skilled players, so they can be creative. Again, if penalties are being committed against skilled players, this should be left to the officials, not the enforcers. But otherwise, if the play doesn’t rise to the level of being illegal, then there’s no issue. A skilled player should have to fight through a fast-paced, tight-checking game to make plays. That makes for good hockey. If a skilled player cannot overcome this, then that’s his issue, not the other team’s.

Another common defense of fighting is freedom of choice. “A player informed of risks should be permitted to assume them,” says Brian Burke. The problem is, neither we nor the players know what fights are doing to their brains, short-term or long-term. As the NHL has argued, the science on CTE is in its infancy. Players likely knew there would be bleeding, bruises, and broken bones. But they probably had no idea they might acquire permanent progressive brain damage. There are several pending lawsuits against the league alleging just that. (Like this one, this one, this one, this one, and this one.)

On a more basic level, though, the willingness of players to endanger themselves is a poor way to decide if something should be permitted. People are willing to do all sorts of unnecessary and dangerous things. Take helmets, for example. There are players who would skate or tend goal without any head or facial protection, if they could. But they no longer can, because player safety comes first, and easily preventable injuries can and should be prevented.

This brings us to what may be the real reason behind the NHL’s infatuation with fighting. We all know it, but players don’t usually talk about it: machismo. The players take great pride in acting tough, and fighting is a huge part of that. Brian Burke, for example, referred to using fighting as a means to control the “rats in the game who live outside the code.” The players seem to enjoy upholding and protecting The Unwritten Code with their fists. Rightly or wrongly, that’s their identity. If that’s taken away from them, then they’re just a bunch of guys with sticks out there.

It’s hard to compete with that mindset. It’s now been more than three years since the deaths of Derek Boogard, Wade Belak, and Rick Rypien, and still the league has never wavered from its wait-and-see attitude on fighting. If their deaths were a wake-up call, the NHL has hit the snooze, and the current prospects for a ban seem dim.

But antiquated notions of toughness were not enough to save helmet-free hockey from exile. And neither should they be enough to save fighting.

Opinion polls (like these in 2009, 2011, 2012, and 2013) show that a growing majority of people — now two-thirds — support a ban on fighting in the NHL. In 2013, GMs Steve Yzerman, Jim Rutherford, and Ray Shero voiced their support for a ban on fighting. Even coaching legend Scotty Bowman went on record saying, “It’s something that has to be looked at.”

The league should stop trying to salvage a dangerous tradition that does no good for players or the sport. It’s time for the NHL to take a long, serious look at fighting’s place in the game.

Jeff, there has been numerous doctors that have done studies that show fighting does not cause head trauma like you are trying to say it does. Head trauma is caused by high speed collisions. I personally played in a league that allowed 2 fights game then went on to play in the NCAA where there is no fighting. I have never been apart of such dirty hockey, which caused more injuries to myself and others in a season that is a quarter of the length of a junior hockey schedule. It is easy for writers to say fighting ruins hockey, but it really doesn’t. Playing in a league where there is no fighting, players have no problem taking a stars head off, because they won’t have any consequence other then a penalty. Players use their sticks and will make dirty hits and head shots way more when there is no fighting, leading to more injury.

710 hockey fights were documented that took place in 1239 games played. It showed the players involved had a 1.12% chance of injury.

Chris, I don’t think anyone’s arguing we should get rid of all physical play, such as checking, hitting, blocking shots, etc. Hockey is, by its nature, a physical game that poses many risks of injury. And you can’t eliminate many of these risks without fundamentally changing the game. So those are off the table. But if something is dangerous and unnecessary (like fighting seems to be), why wouldn’t you want to make the game safer, even a little bit, by eliminating it?

This is such a tired argument, “people can get hurt so we must banish it from existence.” It’s “herd thinking.” Playing hockey in general is hazardous to one’s health. If you added up all the stitches, broken bones, concussions, sprains, separations, bruises & contusions suffers by hockey players in one season, it adds up to way more pain and trauma than is suffered by the game’s handful of pugilists. Regarding the CTE I would reason that the majority of it was received more from those players physical play than fighting. How often do most of the truly tough guys really get hit? The reason they’re able to stay in the league is because they have been able to avoid getting clocked. Those that can’t aren’t in the game long enough to sustain long term damage. Any hockey fan is up for making the game safer for the players up to a point. The safest thing is to have no hockey or sports at all. Where is it written that the goal of humanity is for every single person to be as healthy, safe, and live as long as absolutely possible? Real fun existence. Like I said, this is nothing more than politically correct “herd thinking,” or lack of thinking. I’m going to go have a cigarette despite that it’s not the “absolute best thing” for me right now. I can’t help it y’know….I am human after all.

Seems to me that there are different categories of fighters in hockey. There is: 1) the ‘enforcer/policeman’ who is there when your star player is in need of a bodyguard – think Dave (Cement-Head) Semenko, who played on a line with Jarri Kurri and Wayne Gretzky on the 1980’s Edmonton Oilers (for the record, according to New York Islanders goalie Billy Smith, Semenko had the hardest wrist shot in the league); 2) the fighter who is meant to intimidate the other team, put them ‘back on their heels’, and make them vulnerable to their goal-scoring teammates – think Dave (The Hammer) Schultz of the 1970’s Philadelphia Flyers; 3)the guy who goes out onto the ice, skates over to his counterpart on the opposing team, drops the gloves, pops off the helmet, and tries to bang the other guy silly before the linesmen intervene, and has no other purpose than to ‘light a spark’ under his teammates, or get the crowd more involved – think Colton Orr of the 2011/2012 Toronto Maple Leafs. John Scott makes a valid point; if he were to limit his activities to the first category and abstain from the other two, then he could justify a good position for himself for an extended career (10-12 years). Those whose talent is restricted to categories #2 and #3 should be discouraged from playing in the league. To do that, they need to be made a liability to the team – following a fight, throw them out, and fine them for each violation of the ‘no fighting’ rule in any subsequent games. The league should also fine teams whose players have been so penalized. They need a job, you say? Well, there is always UFC, or Aussie Rules Football…

Do you know what year the NCAA’s ban on fighting was implemented? Because that’s a good question, whether injury rates (or the rates of concussions or certain types of penalties) went up afterwards. To my knowledge, no one has actually looked at that, and I tried to find data that would let me figure it out, but came up empty. Does anyone know of any resources that could help shed some light on this?

I don’t really agree when you say, “In none of these leagues, however, is there any evidence of an epidemic of dirty plays.”

I think if you look at the way play has evolved in NCAA hockey since the introduction of the “new standard of play”, the number of injuries resulting from dangerous body contact has increased. By dangerous body contact, I mean blind-side body checks, contact to the head, charging, and hitting from behind.

It’s also been argued by some people involved in college hockey that since the 1980s mandatory full face shields have played a major role in a greater amount of high sticking and head contact taking place at that level. At least when NCAA Men’s Ice Hockey is compared to other levels of hockey with players of comparable or higher skill levels.

Dave Aiello is right, while there aren’t many fights in NCAA hockey, there’s still dirty play. Instead of the fights you get more stick work and checks from behind. Former UND and Calgary Flames hockey player Perry Berezan said that the mask actually made the game dirtier.