Though the traditional big four teams (the Eagles, Flyers, Phillies, and 76ers) dominate Philadelphia’s sporting landscape, the city also has a rich history of franchises that do not quite “count.” Some have been a pleasant distraction; the Soul won three Arena Football titles before going belly up, while the lacrosse Wings won double that amount in their original run. Others, like the soccer Fury and World Football League Bell, fizzled out so quickly they will only ever be remembered as Quizzo answers, and that’s if they’re lucky.

No “extra” team enjoyed quite as strange a tenure in Philadelphia as the Blazers, a hockey team that made Paul Newman’s Slapshot seem comparatively mundane. Celebrating their 50th anniversary this year, the team had it all: a disastrous debut, a star player more concerned with Playboy Bunnies than pucks, and a monstrous payroll destined to end in disaster. Today, there are no murals or plaques in Philadelphia to commemorate the Blazers. But maybe there should be; the story of their whirlwind inception and spectacular demise is just too bizarre to forget.

The World Hockey Association: Hockey’s New Frontier

To understand the complex albeit brief history of the Blazers, one must first understand the World Hockey Association (WHA). The WHA was an outlaw league not unlike the more famous American Basketball Association, the original home of National Basketball Association teams like the Nets and Spurs. Both leagues poached stars from their more established rivals, both expanded the appeal of their respective sports, and both had epically flamed out by 1980. The WHA’s goal was to identify major metropolitan markets starved of pro sports and take on the NHL. That job was simplified by the success of the NHL’s 1967 expansion and nonexistent presence throughout most of Canada.

Related: The WHA – A Look Back at the Upstart Hockey League

The 1967 expansion teams, known to hockey fans as the “Second Six,” had seen considerable financial returns in Minnesota, St. Louis, and Philadelphia by the time of the WHA’s 1971 inception. The nascent league’s founders took this to mean hockey had legs in America. Add in the absence of pro hockey in major Canadian hubs Calgary, Edmonton, and Quebec, and they had sufficient urban markets to begin a brand new league.

The Miami Experiment Ends Up in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, naturally, had no place in the WHA’s original vision. Ed Snider had dragged hockey to the city kicking and screaming in 1967, and had only just begun assembling the core of his back-to-back Stanley Cup winners by the time the Blazers rolled around in 1972.

Superstar center Bobby Clarke was already one of the league’s best two-way players for the early Flyers, but beyond him, scoring was hard to come by. It was not until the 1972-73 season that forwards Bill Barber and Rick MacLeish would emerge as elite players. Just as importantly, legendary scrappers Dave Schultz and Andre “Moose” Dupont had not terrorized the league on Clarke’s behalf until that season. Sure, the Flyers were steadily improving, but before 1972-73, there was not yet any indication of the wild sporting and financial success of the “Broad Street Bullies” era, much less reason to believe there was room for another hockey team in Philadelphia. So how did the Blazers settle on Philadelphia? Simple: Miami was not available.

The Miami Screaming Eagles were to be one of the WHA’s charter teams, a bold charge into sunny Florida decades before the Tampa Bay Lightning and Florida Panthers were even a twinkle in the NHL’s eye. The league failed to appreciate that with no indoor sporting arena, Miami could not plausibly host thousands of suntanned new fans for its would-be hockey team. When the municipal government balked at a proposal to gut and convert an office building into an ice rink, the Screaming Eagles were dead in the water before they had even gotten off the ground.

The new league was spared an egg bound for its face when Bernard Brown took the husk of the Screaming Eagles, defunct before ever playing a game, north to his native Philadelphia. Brown, a Temple alum who skipped his degree to take over his late father’s trucking business, had become an institution in the freight industry with ties in everything from higher education to horse racing. Brown built his business empire from a few garbage trucks, and was remembered by his son as “one of the last hard-driving, hardworking truckers … a real pioneer in innovation, in equipment specs.”

The Blazers, as they would be called, were Brown’s chance to give back to the region where he had earned his fortune. Give back he would, to the tune of over $3 million in payroll. Brown and Blazers president James Cooper, an Atlantic City attorney who went in with Brown for the team, would start by honoring the contracts signed by the Miami franchise. One was signed by the WHA’s first poached NHLer. Christened “hockey’s first rebel” by the newspapers, that player was a talented but mercurial goaltender named Bernie Parent.

Brown and Cooper would couple Parent, who had already played in Philadelphia before achieving mythic status, with another popular former Flyer, slick centerman Andre Lacroix. The next domino to fall was the Stanley Cup champion Bruins’ John “Pie” McKenzie, a hard-nosed former All-Star on the wrong side of 30. Parent and Lacroix would put on a friendly face for their new/old fans, McKenzie would serve as player-coach, and Rangers legend Phil Watson would oversee the day-to-day hockey operations of the new franchise. With the arena that eluded the Miami team secured in the form of the 9,600-seat Philadelphia Civic Center, the Blazers were well on their way. They only needed a star player.

The Derek Sanderson Gamble

History remembers Bobby Hull as the WHA’s biggest coup, with his garish million-dollar check and immediate MVP season for the Winnipeg Jets. Things are simpler that way, with an aging but still primed Hull netting 50 goals as though it were as simple as lacing his skates. Even Gordie Howe’s triumphant return from retirement with the Houston Aeros a year later would paint a pretty picture of the paradigm shift begun by the WHA. The truth though, is that neither Hull’s big check nor Howe’s hockey resurrection was half as ambitious as the Blazers’ attempt at landing a superstar.

Brown, Cooper, and Watson would not pursue giants of the sport in the twilight of their career as had Winnipeg or Houston. They had a better idea. The Blazers wanted to land one of hockey’s most recognizable faces at the peak of his powers. They wanted Derek Sanderson.

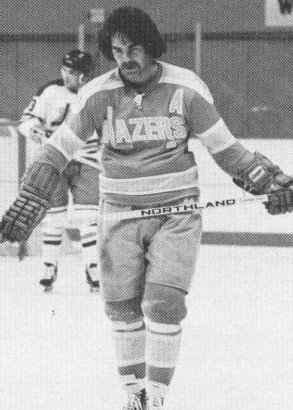

Sanderson was a hard-hitting, hard-partying playboy whose movie star looks contrasted starkly with his intense game. Sanderson was no Hull as an NHLer, good for around 60 points and 150 penalty minutes over an 80-game season, not that he ever managed one. What the Blazers were paying for was his celebrity. Sanderson was a contributing member of a Bruins squad that had just won two Cups in three seasons, but hockey only accounted for half of his visibility.

The handsome center had appeared on television with Johnny Carson and was a frequent topic in the tabloids. Cosmopolitan hailed Sanderson as one of the 10 sexiest men in America, and in 1970, he published his first autobiography at the ripe old age of 23. Later, Sanderson admitted that the book, I’ve Got to be Me, took about 18 hours of his time. He palled around with Joe Namath, and it was not uncommon for him to spirit large groups of single ladies away to Hawaii. The Blazers hoped he would lend the WHA the same credibility Namath had lent the American Football League by signing with the Jets 10 years prior. There was no doubt about it; in Sanderson, the Blazers had found their guy.

Brown and co. were so sure that Sanderson’s play, and more importantly his face, would put butts in the Civic Center’s seats that they paid him $600,000 at signing. Sanderson joked that the Blazers “made [him] an offer he couldn’t refuse.” Earlier in the summer he had jousted with the Bruins for a raise to the tune of $80,000. Now, with a contract worth upwards of $2.6 million, Sanderson would make more than his buddy Namath, more than his Bruins teammate Bobby Orr, more than Tom Seaver, and more than Pele. The Blazers made Sanderson, a newly 26 career second-liner whose only individual award was the 1968 Calder Trophy, the world’s highest-paid athlete.

Opening Night, Friday the 13th

Sanderson was to be the keystone piece of the Blazers’ hockey puzzle, a lightning rod that put eyes on a roster that included just seven other former NHLers. One of them, a defenseman named Irv Spencer, had not suited up in that league since 1968. Others, like Danny Lawson and Bryan Campbell, had talent but had yet to put it all together over a full season. It was up to Sanderson to lead the team into its inaugural season as Parent and McKenzie recovered from injuries sustained in the preseason. He was the captain after all, and a stipulation of his contract ensured that he always would be.

6,000 tickets were sold to the Civic Center, a 40-year-old building that had never hosted a hockey game, for the team’s home opener. The Beatles, the Stones, and the Jacksons had played there, but never ice hockey. The tilt with the New England Whalers would be a maiden voyage for an old vessel, scheduled to take place during the second weekend of October 1972. The puck would drop at 7 pm, Friday the 13th.

No one had taken the ice by 7, though. Representatives from both squads anxiously surveyed an ice surface that more resembled roadside slush than a deep frozen pond. The arena, which was this team’s one leg up on the abandoned Miami franchise, threatened to fail them on opening night. Some Blazers had already urged officials to call off the game, but Cooper assured them a late arriving Zamboni would smooth the rink and that they would be off and running (or skating) in no time.

The machine arrived just after 8 to placate the increasingly restless spectators and spare the organization’s blushes. Cooper, rookie coach McKenzie and a crowd that included Mayor Frank Rizzo watched with bated breath, waiting for the choppy ice to transform into a sleek, professional-grade playing surface. Instead, it buckled under the weight of the three-ton Zamboni. The ice cracked into a thousand fractures.

Cooper and a few other suits had the bright idea to convene on a carpet laid out for a ceremonial puck drop at center ice when one of the red souvenir pucks given out to the Philadelphia fans was thrown in their direction. Then two. Then ten. The brass turned to Sanderson to talk down the growingly rabid fans after they had officially called the game. Sanderson later claimed Rizzo offered him some sage wisdom on the city’s volatility. “Don’t touch that microphone,” the former chief of police advised. “Nobody can calm those people down.”

Still, Sanderson marched out in his skates to address paying customers who had by now waited two hours just to watch ice fail a stress test. “I’m going to hang around,” Sanderson nervously quipped. “I’m not due to pick up my date till 11:15.” The hail of pucks intensified, Sanderson bid the crowd good luck in their escape through the cramped halls of the Civic Center, and the Blazers hid in their dressing room until the chaos subsided after midnight.

The $2.6 Million Man and the $1 Million Buyout

If the ice was a problem for the Blazers in their debut, in the weeks that followed it was what happened on said ice. The Philadelphia team started 0-7, then 2-12, then 4-16. Without Parent, an ancient goaltender named Marcel Paille, who had first suited up in the NHL for the Watson-coached Rangers in 1957-58, was shipping nearly five goals a game. “Maybe I ought to give them back some of the money,” Sanderson mused. “They can have $200,000 if they want it.”

In the midst of the skid, the captain began to thaw from a booze-fueled early-season slump. He netted twice in a triumphant trip to Cleveland against Gerry Cheevers, a former Bruins teammate and future Hall-of-Famer who had also been seduced to the WHA. Just as Sanderson was getting his skates under him, one of them snagged on a piece of trash thrown from the crowd. The $2 million man blew his back after eight games.

In January of 1973, Sanderson’s lawyer Bob Woolf and the Blazers brass, terrified of honoring their full financial commitment to the lackadaisical and now seriously injured superstar, agreed to a buyout of $1 million. Sanderson was in Jamaica when the news broke. By year’s end, he would publish another autobiography. This one took 13 hours. Woolf eulogized the experiment. “Philadelphia did not sell as many tickets as it had anticipated as a result of Derek just being [there]… Derek has some proving to do.” He never did. Hit by injury and alcoholism, Sanderson only played 255 more pro games in a feeble return to the NHL.

The Blazers Go Up in Smoke

Soon, Watson relieved McKenzie, still a productive player, of his coaching duties, and Parent returned to action. Sporting a molded face mask decorated by flames, the Hall-of-Fame goaltender hardly missed another game, starting a ridiculous 63 contests and winning 33. Watson, who had coached nearly 400 NHL games in the ‘50s and ‘60s, righted the ship behind the production of Lacroix.

The French-Canadian would ironically prove the WHA superstar the Blazers had expected Sanderson to be, winning the first of his two Hunter top-scoring trophies. When the dust settled on the WHA, no player had collected more points than Lacroix’s 798. Lawson, of 57 career points in the NHL, exploded for 61 goals in this land of over-the-hill legends, snot-nosed teens, and career minor leaguers. Watson’s Blazers finished a respectable 38-40, good enough for the playoffs.

It mattered none. After the cracked ice debacle, the abysmal start to the season, and the failed Sanderson gambit, the Blazers spent all their money and goodwill. Worse yet, the rival Flyers were a runaway train that there was no keeping up with. Clarke won his first Hart Trophy as league MVP, Schultz and Dupont beat up half of the league, and coach Fred Shero led the Orange and Black to both their first winning season and first playoff series win.

Five miles up the Schuylkill Expressway, the Blazers were barely drawing 4,000 fans a game, third-worst in the WHA. “We had more people watching our practices in Boston than our games in Philadelphia,” Mackenzie lamented.

Related: Broad Street Bullies: More Than Goons, Fists & Enforcers

During the playoffs, Parent realized he was not receiving payments insured against the WHA’s demise, a stipulation in his $750,000 deal. He bolted on the team, never to play another game in the WHA, while the Blazers were swept 4-0 by Cheevers and the Cleveland Crusaders. Parent was relieved to return to a more professional outfit, the Flyers. “Even when I’ve been away,” he promised, “I’ve always considered myself a Flyer.” In each of the next two seasons, Parent collected the Vezina Trophy as the league’s best goaltender, the Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP, and the Stanley Cup.

For the Blazers, the writing was on the wall. Just as Brown had purchased the corpse of a failed franchise from Miami, industrialist Jim Pattison took the money-draining Blazers west to Vancouver for $1.9 million. Brown and Cooper had paid $1.6 million to Sanderson alone. $200,000 for every game, $333,333 for every point. As suddenly as the Blazers had burst onto the scene, they vanished.

Maybe things would have been different for the Blazers if Watson had been behind the bench from day one, as opposed to McKenzie, who had never coached a game before 1972. Maybe they would have had more success with a team full of young, hungry pros like Lawson and Campbell, who scored 73 points. Sanderson sure thought spending big money on big names was a foolish play. “All that money has an effect on you. You don’t want to suffer. You don’t want to put up with the sweat, the bleeding, the pain it takes to win.”

The Blazers are not memorialized in any significant way, it is true; there are no bars named in their honor, no orange and yellow jerseys hanging in Xfinity Live. At face value, that makes sense. After all, the team only ever played 82 games, and only ever won 38. Their tumultuous history, though, is worth at least a TV special. It’s the kind of weird that’s worth remembering.