NHL players are unlikely to receive the headline contract salaries you see proposed, traded and debated this week because the actual cash players receive is subject to a higher power: NHL revenues. Players are only entitled to share 50% of the total revenues of the League, a number which is typically less than their contracts’ total. Team owners get the other 50%, no matter what the contracts with players say.

The 2017-18 Salary Cap Rose Again

While players and fans await the outcome of the Las Vegas Expansion draft and the 2017 NHL Draft, the NHL and the NHL Players Association (NHLPA) jointly announced on Sunday, June 18th, a $2 million dollar rise in the 2017-18 salary cap.

Teams can now pay their team up to $75 million in salaries next season. Teams, and many of their twitter-enabled fans are visibly thrilled they can now bid higher for the best players. But why did this happen? Does being able to spend more on player salaries mean better teams for everybody and more money for all players?

No. At heart, the NHL and the NHLPA are an uneasy marriage between free market capitalism and socialism. Teams compete in the free market for the best talent, and typically the best players go to the highest bidder.

But the contracts these players sign is only as good as the revenues the League earns, as a collective. And for almost a decade, players have had to give money back —money from the headline salaries in their contracts — to the team owners. So why did the NHL and NHLPA raise the cap again?

The NHL Makes Money & More Every Year

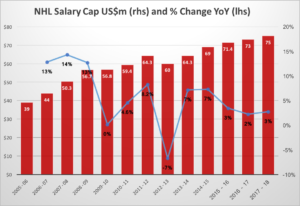

The chart below shows the total revenue earned by the NHL in the last decade, in billions of dollars. Revenues have climbed from $2.27 billion in 2006 to $4.1 billion in 2016, an increase of 81%, or about 10% per year. If League revenue is rising around 10% a year, and teams and players have to split revenues 50/50, then it seems reasonable that players salaries should increase about 5% a year. And this is exactly what that Collective Bargaining Agreement (the CBA, which governs the relationship between the teams and the players) says will happen.

Section 50.5(b)(i) of the CBA states that team payroll “shall be adjusted upward by a factor of five (5) percent in each League Year”. But in 2017, the Salary Cap was raised $2 million (from $73 million to $75 million), a rise of only 2.7%. If NHL revenue is rising, who agreed to a lower Salary Cap and why?

Who Decides the Salary Cap?

It is a common misconception that the NHLPA decides how much to increase the salary cap each year. They, alone, cannot. The CBA is clear that the salary cap will rise 5% each year “unless or until either party to this Agreement proposes a different growth factor based on actual revenue experience and/or projections, in which case the parties shall discuss and agree upon a new factor.” In other words, everybody (the teams and the players) has to agree to anything but an automatic 5% rise. And they always do. As shown in the chart below, the salary cap has grown steadily, but never at 5.0%.

Had the players and teams not chosen to deviate from the agreement’s 5% annual rise, the 2017-18 salary cap would be $76.7 million (5% greater than last year’s $73 million). The same teams/players now professing joy at the prospect of spending/earning more, agreed to budget less money for salaries than they could have. And this is not new. For years, salaries have increased less than the 5% default as stated in the CBA.

Why Didn’t the Salary Cap Rise More?

The cap didn’t rise because the money to pay players just isn’t there. A rise in the salary cap allows teams to give larger contracts to players, but that doesn’t mean players will actually get paid more. Remember, players can only receive 50% of NHL revenues, regardless of what their contracts say.

What happens in practice is that the NHL calculates an “escrow payment” that comes out of the players’ salary. Payments are deducted from each paycheck and are held in escrow pending a final totaling of the League’s revenues for the year.

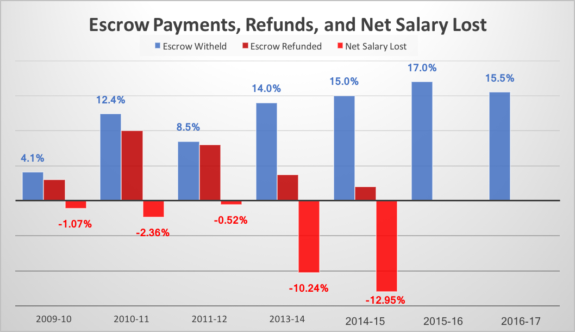

That total is divided in half (50% goes to the owners), and then pro-rated across the players according to their contracts. The chart below shows, by season, the percentage of salary withheld, the percentage of that amount that was ultimately refunded to the player, and the difference between the two, which is the net loss of salary to the player. For example, in 2014-15, players received 12.95% less pay than their headline contract amounts.

Note that escrow payments have been above 15% for the last three years, while escrow refunded has been declining. (We don’t have data for the refund in the 2015-16 season, and 2016-17 hasn’t been calculated yet). The result is a significant salary loss for all NHL players, shown as bright red bars in the above chart. Since 2009, players have given back some of their contracted salaries every year, and this percentage grew rapidly in 2013-14 and 2014-15.

This is why the salary cap hasn’t been raised more and wasn’t raised the full 5% this year – to raise it without a commensurate rise in forecasted NHL revenues will result in a higher escrow payment, which likely won’t be rebated.

That is not to say that there isn’t a lobby amongst the players to raise the salary cap regardless of what it does to the escrow payments. Specifically, those players about to sign new multi-year contracts would rather have the cap raised so they can get paid more whatever the escrow payment is, it’s still just a percentage of their pay raise.

But when raising the cap also raises the escrow payment, players on existing contracts are taking an actual pay cut. So, raising the salary cap is effectively a transfer from players on existing contracts to players on new contracts. You can guess which players are for and against a salary cap raise, and one supposes those debates can sometimes go beyond “roughing”.

Real Salaries Are Going Nowhere Until NHL Revenues Rise

Looking ahead, there is little reason to think the amount of refunded escrow will grow absent a significant rise in NHL revenues. And from where might that come?

The addition of a new franchise, the Las Vegas Knights, generated a $500 million fee for the NHL, a fee that is not only almost 25% of the NHL’s total revenues in 2015-16 but a fee that set an NHL record and is the second-highest fee ever paid in any sport. (That record is held by the Houston Texans, who paid $700 million to join the NFL in 1999). But, sadly, when it comes to sharing revenue with players, the CBA explicitly excludes revenues earned from a new franchise.

Nevertheless, an additional team does mean additional revenue, and while it may not increase the amount of escrow rebated, it may keep next year’s escrow rate from rising significantly, despite the rise in the salary cap.

Nevertheless, an additional team does mean additional revenue, and while it may not increase the amount of escrow rebated, it may keep next year’s escrow rate from rising significantly, despite the rise in the salary cap.

The Gavin Management Group, a financial services firm with a specialty in managing NHL players, expects that “the escrow rate remains between 12% and 15%” for next season, “with any decrease attributed to the US revenue derived from the 24th US-based team in Vegas.” Driving this forecast is “the small 2.7% increase in the salary cap to $75 million” and the relative stability of the Canadian Dollar.

The Canadian Dollar? Yes, given that a sizable percentage of NHL revenues are generated in Canada, the fate of NHL revenues is dependent on the USD/CAD exchange rate. While individual Canadian teams can and do use financial derivatives to manage their own exchange rate risk (they must pay their players’ salaries in US Dollars while earning revenues in Canadian Dollars), the League has a harder time hedging their currency risk, leaving player escrow reimbursement rates largely in the hands of the free market.

Until League-wide revenue grows, hockey players will continue to have high-paying contracts, lowered by real escrow payments; the salary cap will continue to rise at a rate below 5%, and players will continue to grumble about escrow payments, and everybody will hope the Canadian Dollar starts to rise.

Oh, and there is another light in the tunnel: In their 2016 financial report, EA Sports notes that their “FIFA, Madden NFL and Hockey Ultimate Team™ live services continued to perform well …collectively up 26% year-over-year” As EA Sports generates net revenue comparable to the NHL’s, perhaps a merger is order?

(Note: The author would like to thank the Lumineers for their presence during the writing of this article)